Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 29th of August 2017 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

When crude oil prices began to collapse from over $100 dollars a barrel in the summer of 2014 to just $40 by the start of 2015, most investors and analysts expected a sharp rebound. After all, oil prices had experienced just such a rebound after a similar collapse in prices during the 2008 financial crisis.

Three years of consistently low prices later those hoping for a rebound in prices must be growing restless.

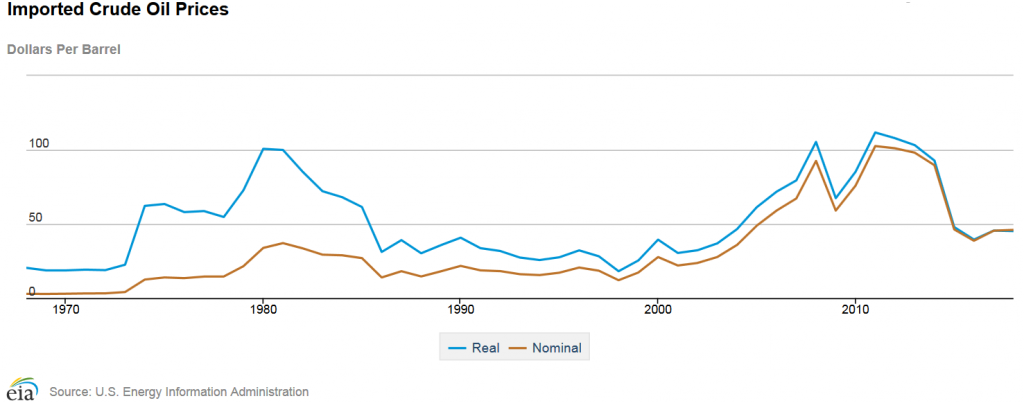

The following chart shows US imported crude oil prices, adjusted for inflation, since 1970. The chart reveals a potential historical analogue to the recent decline in oil prices. In the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, oil reached an inflation-adjusted value above $100 dollars a barrel in the wake of the Iranian Revolution and Iran-Iraq war, only to decline to about $30 by 1986. After 1986, far from rebounding, oil prices continued to trend lower for 12 more years reaching an adjusted low of just $18 in 1998.

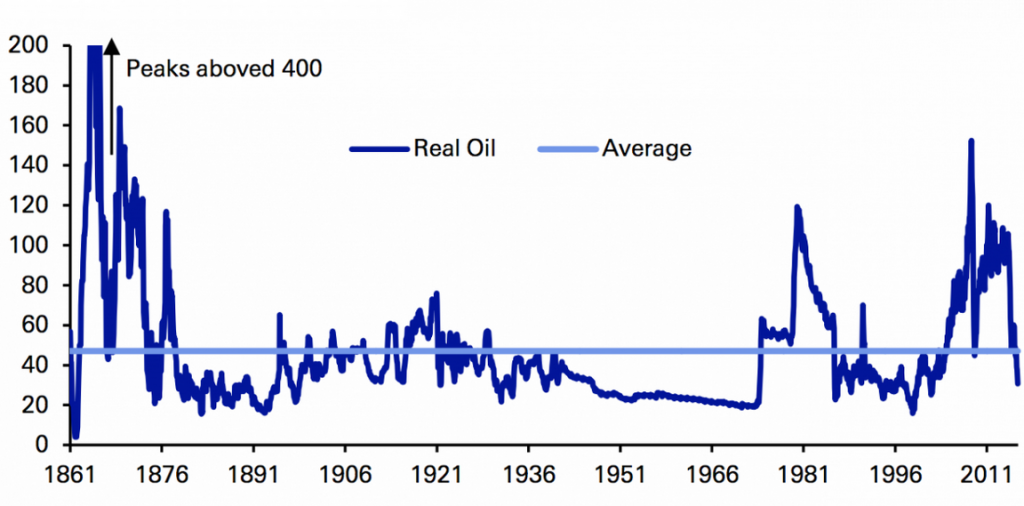

While the reasons for the rise and fall in oil prices are markedly different between the 1980s and today, the more general point remains that oil bear markets (and commodities in general) can, and typically do, last longer than bull markets. With three years of low oil prices already in the books, we are solidly in a bear market (not an anomalous collapse like in 2008), which has the potential to last for many years to come. As the following chart of inflation adjusted oil prices since 1861 shows, the bull market in the 1970’s followed an astounding 50-year bear market, starting in the early 1920s. What’s more, the average real oil price since 1861 is about $45 a barrel, right where we are at the time of writing.

Global oil markets are undergoing structural changes that are contributing to what may be a long term era of low prices. As we noted here, increases in oil production by the US and certain OPEC members have more than offset decreased production associated with the Saudi-OPEC oil production cut deal. This points to an inconvenient truth about OPEC. Excess oil production capacity is more distributed around the world today than it has been in many decades. As a result, non-OPEC producers can and are increasing production to take advantage of OPEC’s self imposed cuts. As we noted here:

“As a result, oil markets have failed to meaningfully reduce oversupply and thus prices have failed to rise. It also implies that the ultimate result of OPEC’s oil cut agreement has simply been to transfer market share from OPEC members who agreed to cut, to the rest of the world, mainly the US. That is not to the advantage of OPEC.

OPEC has been an all-important fixture in oil markets and oil prices for decades based on the idea that it controls enough of oil production capacity to effect market supply and prices. If the result of OPEC oil cuts is only that it permits other producers to take market share, OPEC serves its members little practical utility.”

The oil global industry needs to purge excess production capacity not just excess production. That is unlikely to happen without bankruptcies and long-term under-investment. Barring unforeseen geopolitical developments, that is a long, painful process that may be just beginning.

P.S. If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.