Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 22nd of September 2017 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

A recent Knowledge Leaders Capital article draws worrying conclusions about the Fed’s plan to reduce its balance sheet. As Knowledge Leaders’ describes:

“Yesterday the Federal Reserve officially signaled the beginning of its balance sheet run-off. At this point, that’s old news. But, today the Fed released the Z.1 Flow of Funds, which adds to the intrigue of the balance sheet run-off. Why?

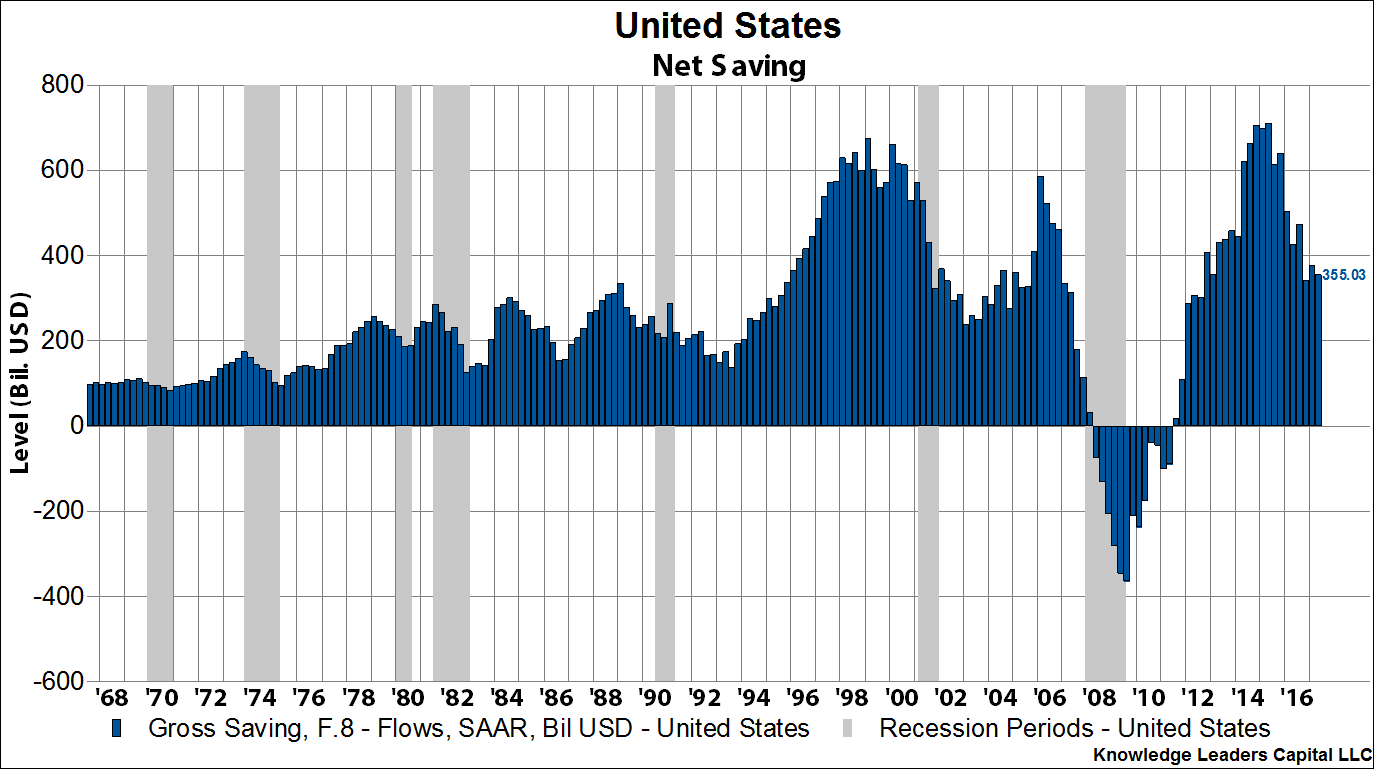

Instead of getting wrapped up in fancy terms like quantitative easing and large-scale asset purchases, I find it easier to think about extraordinary monetary policy from a savings standpoint. Distilled to its roots, the Fed has been manufacturing “savings” from thin air for the better part of a decade. When the financial crisis hit in 2008, American savings were depleted, so the Fed had to step in to produce savings (to finance huge government deficits). Now the Fed is attempting to remove that “savings” at a time when:

- The private sector is experiencing falling savings.

- The government is likely on the precipice of expanding its dis-saving in the form of greater deficits

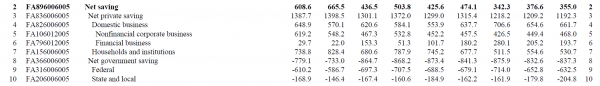

Some data and charts will help explain the concept. In the Flow of Funds, released quarterly by the Fed, the relevant section to this discussion (out the 198 page report) is F.4 – Savings and Investment by Sector. Below is a clip from that table, highlighting aggregate net savings by sector.

A couple quick notes about the above data:

A couple quick notes about the above data:

- Net savings of domestic business is basically undistributed earnings.

- Net household savings is a residual of income minus consumption.

- Net government saving (or dis-saving as is the case) is the aggregate deficits of federal, state and local governments.

These net savings are the aggregation of what is left after businesses replace worn out capital and pay dividends, what households have after paying their bills and what the government has after paying its bills. It is the country’s seed corn. If there is no net savings, there can be no net investment.

The financial crisis of 2008 decimated the stock of savings, and it actually dipped negative for the first time ever. Current aggregate net savings in the US are $355 billion. That’s it!”

Mr. Vannelli goes on to describe the problem with the Fed’s plan’s to reduce its balance sheet:

“If the Fed starts shedding assets at $10 billion/month, ramping to $50 billion/month by 2019, can the private sector absorb these securities at the same the government budget deficit is set to widen by perhaps $100-$150 billion in the next couple years?

Not to state the obvious, but all else equal, if the Fed started shedding assets at $30 billion a month (or $360 billion a year), it would exhaust the entire stock of private savings. This doesn’t allow for larger government deficits. Given the current savings level, it is mathematically impossible for the Fed to shed assets at $50 billion/month. By 2019, as we are farther out from peak net savings rates set in 2015, it is likely the stock of private savings is smaller still, and hence the ability for the Fed to shed assets at a rate of $50 billion/month is utterly impossible. Net savings have fallen in the last 2 years from a peak of just over $700 billion to the current $355 billion. Will savings halve again in the next two years? If so, there is no mathematical way in the world the Fed can shed assets at the rate it outlined yesterday.”

All of this goes to highlight an important point: the QE programs initiated by the Fed were designed to boost risk asset prices and lower interest rates and they succeeded in doing both (though that didn’t translate into broad based economic growth and wealth distribution). The programs achieved this ‘success’ by creating artificial demand for financial assets. Reversing these programs by reducing the Fed’s balance sheet, however slowly, will have the opposing effect. Shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet will reduce demand for financial assets. Mr. Vannelli makes the important point that, based on the net US savings rate, it will be difficult for the US economy to absorb the missing demand, even given the Fed’s ultra-slow timeline.

However, Mr. Vannelli’s analysis, like many others, does not account for over $2 trillion in excess bank reserves that have accumulated at the Fed in recent years. As we have discussed on numerous occasions, one of the side effects of the Fed’s QE programs has been unprecedented growth in excess bank reserves parked in cash at the Fed. While these excess reserves are currently at the Fed, under the right conditions, the excess reserves could begin to flow into financial assets, like treasuries and mortgage backed securities. This would more than make up for the missing demand caused by the Fed’s balance sheet reductions.

If the Fed needs to, it could incentivize these excess reserves to flow back into financial markets by reducing the interest rate it pays banks on their excess reserves. In this way, the reduced demand for financial assets resulting from the Fed’s balance sheet reduction could be made up for and any negative effects postponed for some time.

If the Fed needs to, it could incentivize these excess reserves to flow back into financial markets by reducing the interest rate it pays banks on their excess reserves. In this way, the reduced demand for financial assets resulting from the Fed’s balance sheet reduction could be made up for and any negative effects postponed for some time.

In any event, the Fed is now in very dangerous uncharted waters.

P.S. We recently added email distribution for The Sounding Line. If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

What about the BOE, BOJ or ECB? Wouldn’t the pick up the slack? Or is the FED the only cowboy in town?

The BOE, BOJ, and ECB wouldn’t likely purchase US Treasuries or mortgage backed securities directly, they would only buy their own nation’s bonds. However, their QE programs create general liquidity that could flow into US assets eventually. So yes, they could indirectly pick up some of the slack too, potentially quite a bit.

Can foreign Central Banks purchase US equities? If so, then the Fed can buy foreign equities and at the same time foreign CBS could purchase US equities. That way the Stock market goes up to infinity as the purchasing power of fiat achieves toilet paper status

Yes foreign central banks can buy US equities and do. The Swiss National Bank has become one of the larger buyers of US stocks.