Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 26th of December 2018 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

If the financial world is surprised by the sell-off in markets this year, it is suffering from history’s worst case of collective amnesia.

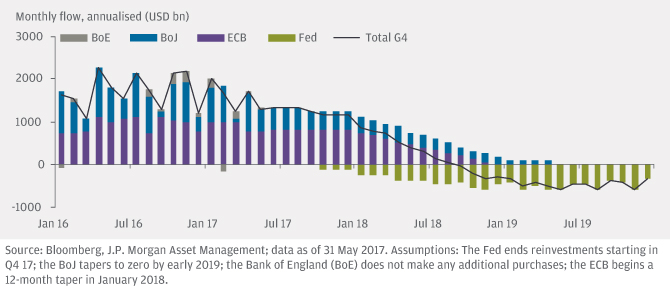

After a decade of unbridled money printing, the high correlation between growing central bank balance sheets and rising financial asset prices has been well documented and exhaustively discussed for years. The concept is so ubiquitous that it underpins the passive investment strategy that has predominated this investment cycle.

The combined balance sheet of the four major global central banks (the Fed, ECB, BoJ, and BoE) finally stopped expanding in mid 2018, as had been the forecast for at least a year. Correspondingly, almost every financial market in the world is declining, with virtually all global markets peaking within a couple months of the central bank balance sheet expansion ending.

After witnessing QE’s effect on markets for a decade, how can the market weakness since its conclusion possibly come as a surprise? The only thing that should have been surprising, and it surprised yours truly, was that the market didn’t price in the highly telegraphed end of global QE a lot sooner.

Meanwhile, everyone seems to be convincing themselves that the current sell-off is premature because economic data does not yet suggest an imminent recession, at least not in the US. Just as financial markets rallied for years despite a dreadfully weak economy, leading to a historic wealth divide and massive social disenfranchisement, markets are perfectly capable of falling when the actual economy does well. The difference is whether or not central banks are growing or shrinking the hundreds of billions of dollars of financial asset purchases that they make every year.

As our good friend Thurstan Timber recently mused, “It just doesn’t feel like there is that much selling in this selloff. Nobody is shorting. People are holding for the bounce.” The missing ingredient is central banks, the marginal buyer for the last decade.

Does that mean that the market is headed for disaster in a straight line? No. Even a bear market has rallies, and the current market selloff is likely no exception. As we noted on October 3rd (coincidentally also the day of the last high on the Dow):

“Whenever markets start to get really dicey again, the main thing that central banks will remember about QE is not the wealth divide or other ‘second order’ concerns but the fact that it succeeded in reflating asset bubbles. So while central banks are unlikely to reverse tightening for any run-of-the-mill market ‘dip,’ you can bet at least some of them will dust off the printing presses for a bone-afide market panic or recession. And while renewed stimulus will come with all sorts of concerning ‘second order’ effects, it will probably succeed again in driving up asset prices. Printing unlimited amounts of money and buying financial assets tends to do that.

So while bad news may finally be bad news again, very bad news may very well be the best news of all for markets. Until very bad news arrives, the market is going to have to fend for itself for the first time in a decade.

Out with BTFD and in with BTFR (Recession), aka ‘be cautious until things get really bad.”

While I am not sure that things are ‘really bad’ yet, markets are certainly on their way there fast.

P.S. If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.