Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 30th of November to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Back in February of 2016 we published an article which argued, amongst other things, that the experimental monetary policy adopted by the Federal Reserve after the 2008 financial crisis had succeeded only in elevating risk asset prices, not in simulating fundamental economic growth or broadly distributed wealth creation (link here).

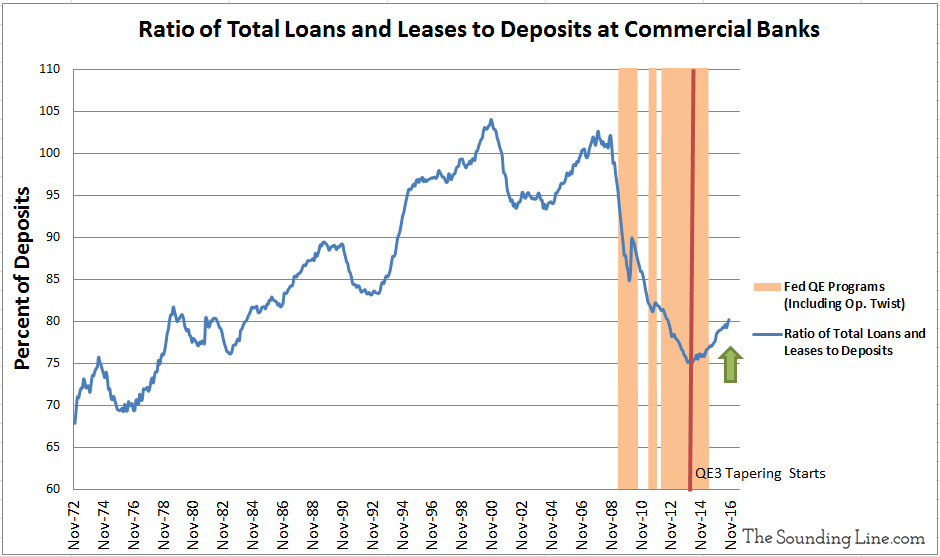

Amongst the evidence presented that the Fed’s policies (zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) and Quantitative Easing (QE)) had failed to stimulate real economic activity was the declining ratio of total loans and leases made by commercial banks to commercial bank deposits. Despite the Fed suppressing interest rates and injecting banks with cash, less and less of the money deposited at banks was actually being loaned out.

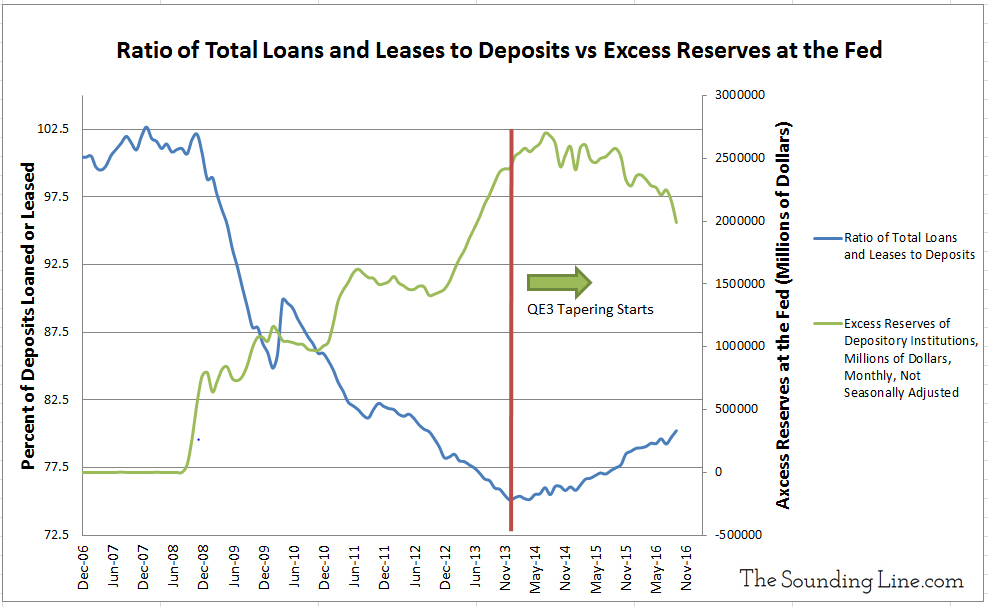

We hypothesized that the failure of the programs occurred, at least in a proximate sense, because while the Fed injected commercial banks with literally trillions of dollars via its various QE programs, they simultaneously implemented a policy of paying banks interest on reserves kept at the Fed. As a result, the banks chose to park the Fed’s newly created QE money right back at the Fed to collect interest without any of the risk and overhead associated with actual banking. Money that was ostensibly created to facilitate affordable bank lending to would be homeowners, consumers, and businesses never left the financial system, serving as little more than welfare for banks.

Enough time has now passed since the Fed began tapering its QE3 program (December 2013) and eventually, modestly raised the Fed funds rate (December 2015) that it warrants taking a fresh look at bank lending behavior.

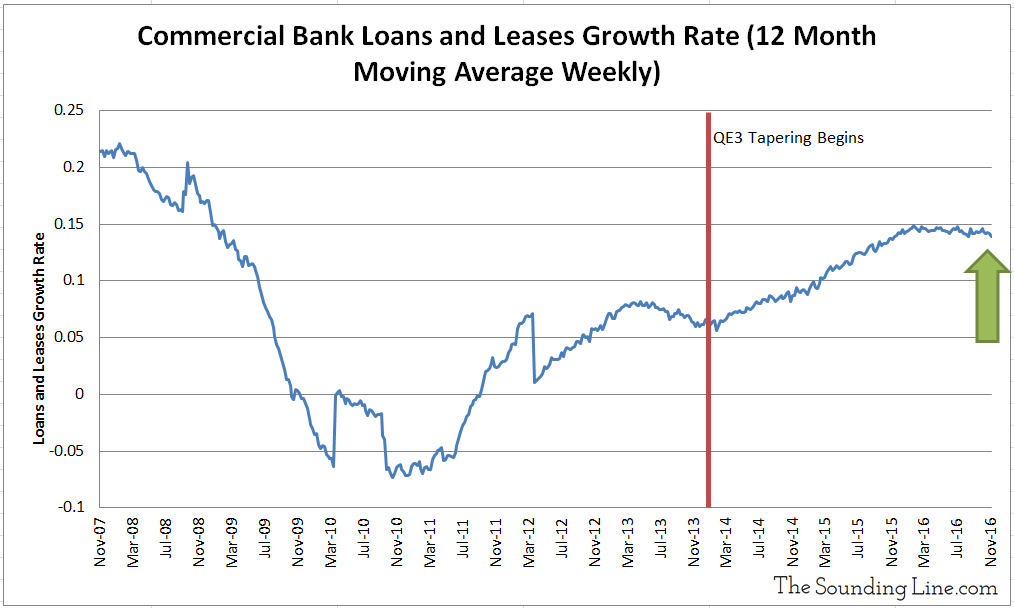

Confirming our suspicions, the charts below show that once the Fed began to normalize its policy so did the banks. Banks are just now starting to lend out more of their deposits and remove some of their excess reserves from the Fed. The Fed’s policy of paying interest on excess reserves remains in effect, and nearly $2 trillion of excess reserves remain at the Fed. Yet, that amount of excess reserves peaked in September 2014 nearly simultaneously with the Fed ending its QE3 program.

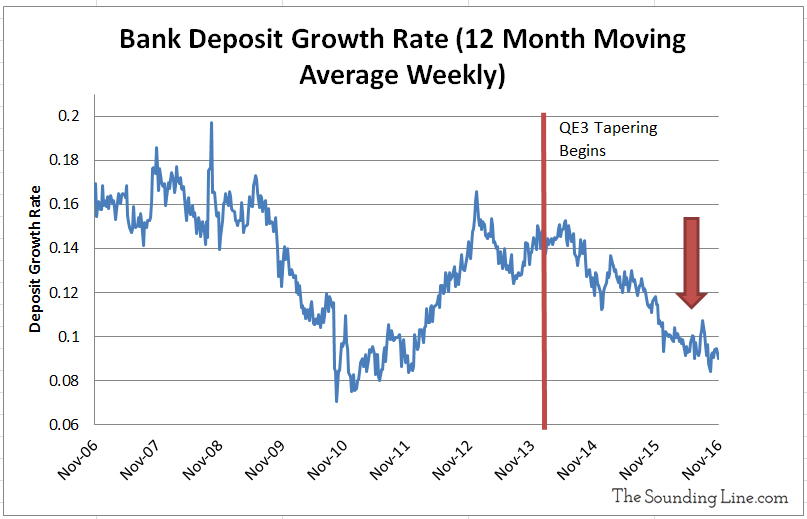

Taken all together, the very modest normalization of US monetary policy seems to have led to a very modest normalization of bank lending. To the extent that increased bank lending is stimulative for the economy, this should be taken as an encouraging sign. However, before getting too optimistic, a bit more digging reveals that one of the reasons that lending is consuming more of bank deposits is because bank deposit growth is at its slowest rate since 2010. Add this to the long list of indicators that suggest that the US economy is still struggling with fundamental weakness.

At the same time lending growth has risen.

The key moving forward will be to observe what effects future interest rate hikes have on lending and excess reserve levels at the Fed. It is assumed that the Fed will also raise its interest rate on excess reserves rate by an equal amount. If real economic fundamentals remain weak, it’s possible that at high enough rates money could be sucked back out of the economy and return to the Fed to collect interest and mitigate risk for banks. For now there is still nearly $2 trillion in reserves at the Fed, and if it does flow out into the ‘real’ economy, it is likely to bring inflation with it. It would be wise to keep an eye on where that money goes.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.