Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 19th of July 2019 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe.

A persistent problem throughout history has been how to construct a monetary system that prevents governments from inflating away their currencies through endless deficit spending. Various solutions to this problem have emerged over the centuries. Today, none of them are being employed.

Precious Metals

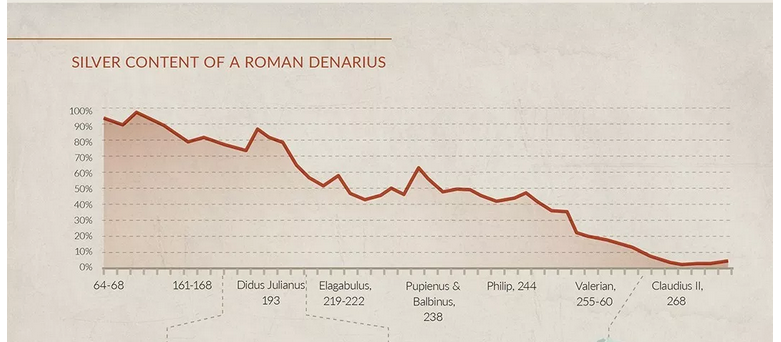

Until modern times, the constraint on government spending was typically achieved by using precious metals as the predominant currency. Because of their rarity, using precious metals as a currency directly limited the ability of governments to grow the monetary base (print money) in order to finance their deficits. Every ounce of gold that a government wanted to spend had to be collected from someone or mined and very little could be mined in any given year.

The problem with this system is that it prevented governments from promising people everything for free. Always desperate to pay for things without actually paying for them, governments put less and less precious metals into their coins and hoped that nobody would notice. People did notice and it invariably led to inflation.

Asset Backed Currencies

With the advent of increasingly large banking networks, it became possible to transfer ownership of physical assets without actually carrying them around with you. In this way, bank notes and paper currencies gradually came to replace precious metals as the predominant currencies. However, until 1971, these paper currencies were almost always still backed by real assets. The requirement that paper currencies be backed by real assets meant that governments could not perpetually spend more than they received in taxes by printing money. To print money required actual assets.

Like with gold and silver coins, the problem with this system is that governments inevitably ended up cheating. They would simply create more paper currency than was permitted by their assets, hoping people didn’t notice. People did notice, invariably leading to inflation. Most of these asset backed paper currencies systems died when US President Nixon closed the Gold Window in 1971. The last gold backed currency, the Swiss Franc, stopped being explicitly gold-backed in 1999.

With the rise of banking also came the rise of fractional reserve lending, whereby commercial banks lend out more money than they actually have. Money creation, something that was previously the exclusive domain of governments, was now happening in the commercial banking system. This led to the need to regulate commercial bank credit creation.

Modern Central Banking

In modern finance, central banks are supposed to play the role that was once played by gold and silver: constraining growth in the money supply. They do this in two ways.

First, central banks regulate lending ratios and interest rates at commercial banks. This constrains commercial banks’ ability to increase the money supply too quickly.

Second, central banks entirely deny governments the right to print their own money. Governments, such as the US federal government, must borrow from investors in order to finance any deficit that they run. In this way, government deficits do not increase the money supply. Money is simply transferred from an investor to the government via a bond.

Postmodern Central Banking

Central banks’ response to the Global Financial Crisis has fundamentally inverted their role in the economy. Institutions that were designed to limit credit creation and prevent the monetization of government debt now view their mission as doing the opposite. Central banking has become so abstracted from its original purposes that people must strain to remember what they actually were actually created to do.

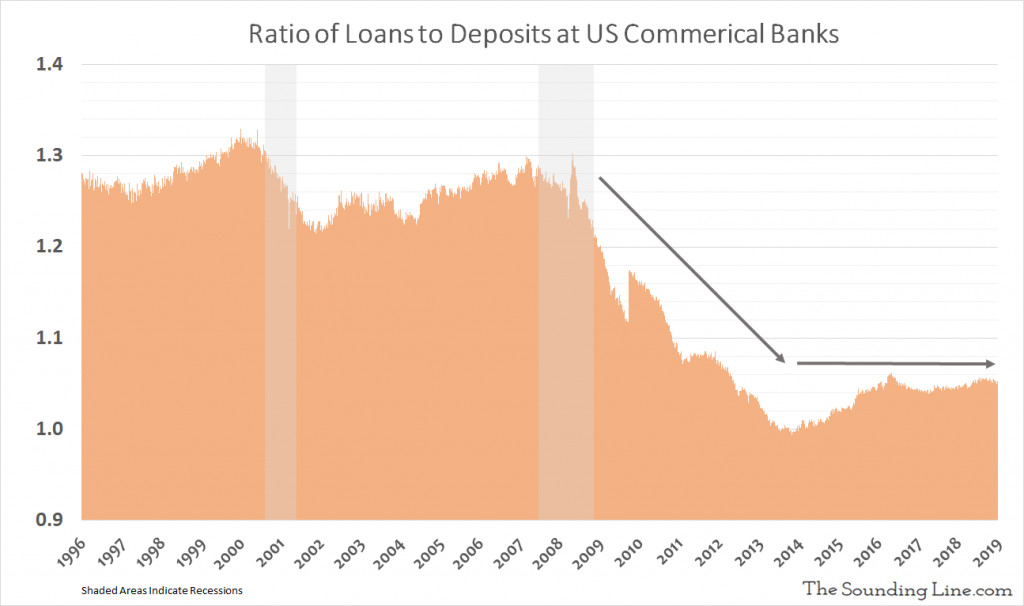

Since the Global Financial Crisis, persistently anemic growth and new banking requirements have kept commercial bank lending ratios significantly lower than they were before the crisis. This has been dis-inflationary.

Artificially low interest rates were intended to improve these low lending ratios. They have largely failed to do so.

Instead of spurring an increase in demand for bank lending, which primarily flows to households and small businesses (that are already struggling with high debt levels and stagnant incomes), low interest rates have led to dramatic increases in corporate and government borrowing. The ‘problem’ with corporate and government borrowing is that it is primarily done via bonds, not bank lending, and does not add to the monetary supply.

The result is a slow rate of growth of the money supply from fractional reserve lending, and a dramatic increase in exactly the type of debt that doesn’t stimulate inflation but does constrain future economic growth by diverting investor capital to economically unproductive businesses and the government.

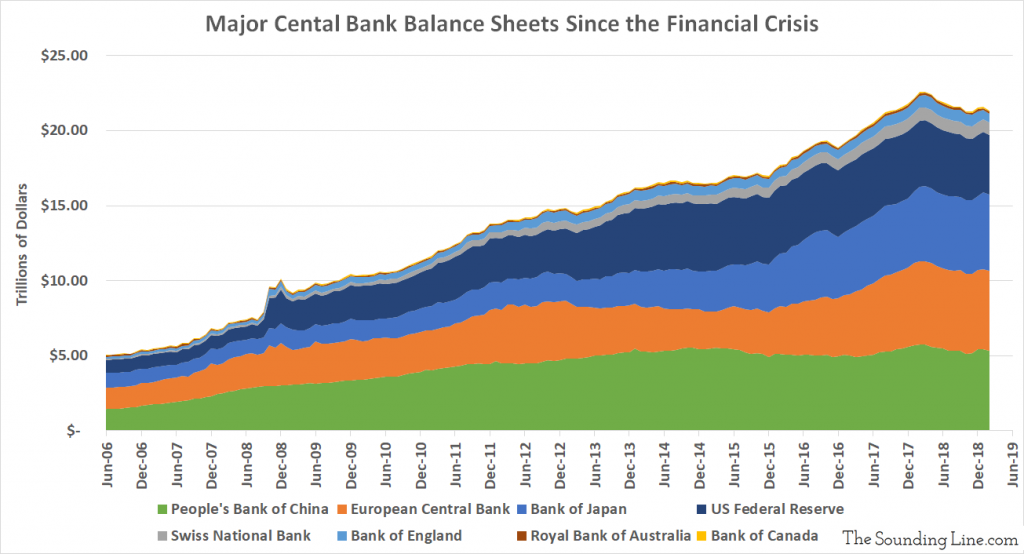

To counter-act the failure of low interest rates to work as desired, central banks have turned to another bad idea: directly monetizing government deficits. In the Eurozone and Japan, where credit growth has been particularly weak, their central banks are monetizing their national debts faster than the governments can even borrow.

The entire structure of central banking was intended to prevent government deficit spending from adding to the money supply. Nonetheless, government deficits are now being intentionally monetized. At first, this was part of a recovery plan to combat a once-in-a 100 year recession. Now it is being sold as part of a plan to avoid a modest slowdowns in growth, the likes of which the world has experienced every few years since the dawn of time.

What About the Future?

Central banks tell us that it is okay to monetize government debt because they are combating deflation. Meanwhile, they are enabling government spending to rise to levels that would be completely unsustainable if central banks weren’t monetizing their debt.

In other words, central banks are not monetizing the national debt to keep governments solvent, but if they were to stop, governments would become rapidly insolvent. At a certain point, the ‘why’ behind a bad idea becomes irrelevant.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

USA didn’t have the last asset backed paper currency – as far as I know, it was Switzerland that went off gold standard as the last sovereign country (under both global and local pressure – their currency was not depreciating as fast as other countries’). “In 1999, Switzerland became a signatory of the so-called Washington Agreement on Gold Sales (WAGS), joining most of the OECD ‘hard currency’ countries.” https://www.globalresearch.ca/the-swiss-national-bank-snb-and-the-save-the-gold-of-switzerland-initiative/5418622 There is still ongoing discussion in Switzerland whether this should be so – see the last years referendum: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2018_Swiss_sovereign-money_initiative Not an economic powerhouse, however, I felt like I should point this… Read more »

Very good point, you are correct. I’ll edit the article.

My recollection is that the Swiss Franc was not actually redeemable in gold though.

The Federal Reserve is responsible for allowing the world to embark on this huge and rapid expansion of debt and credit during the last decade. This could not and would not have occurred without the Fed being totally complicit. A key role of a reserve currency is to force other currencies to toe the line or pay a stiff price. Ignoring this economic reality translates into pain for those holding the currency of any country that abuses this economic law. It has been the Fed that decided to allow the dollar to be used as a global prop. Trump’s desire… Read more »