Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 19th of January 2017 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Not too long ago we posted this article in our ‘Top News Stories’ column, summarizing a study from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The article warns of a food shortfall facing sub-Saharan Africa in the coming decades. A similarly ominous forecast from the UN calls for a 40% global water shortage by 2030. It’s probably a fool’s errand to quantify exactly when such problems will arrive and what their magnitude will be, but these studies, and others like them (here) raise an important question:

Can the world’s agricultural system continue to meet the needs of its growing population?

After years of declining agricultural commodity prices it may be hard to imagine a serious food shortfall in the relatively near future.

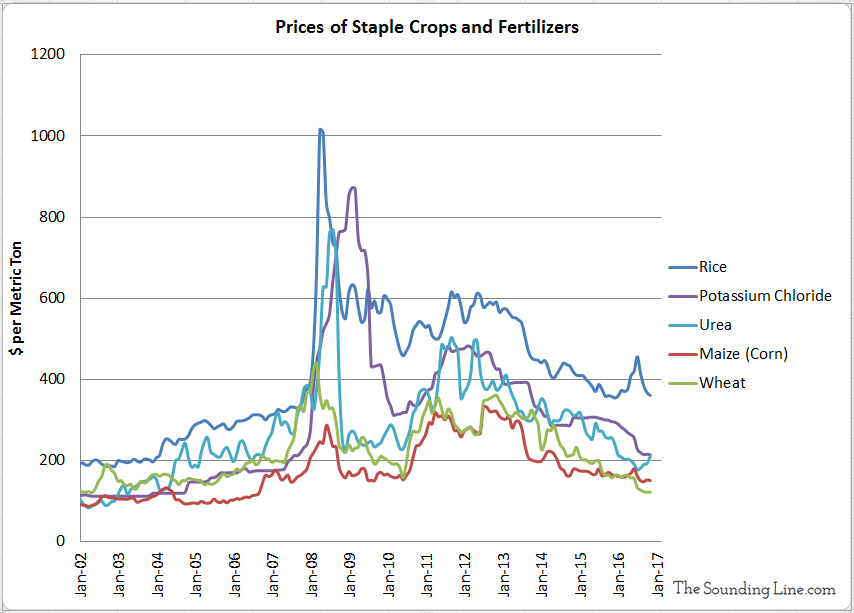

A quick survey of the prices of basic cereals (rice, corn, and wheat) that make up the vast majority of calories consumed by humans, and the fertilizers used to grow those crops (potassium chloride and urea), show several fold price declines since peaking in 2008.

These price declines have helped to hold food prices down for many of the world’s poorest countries. Yet the long term trends underlying food supply and demand dynamics are concerning.

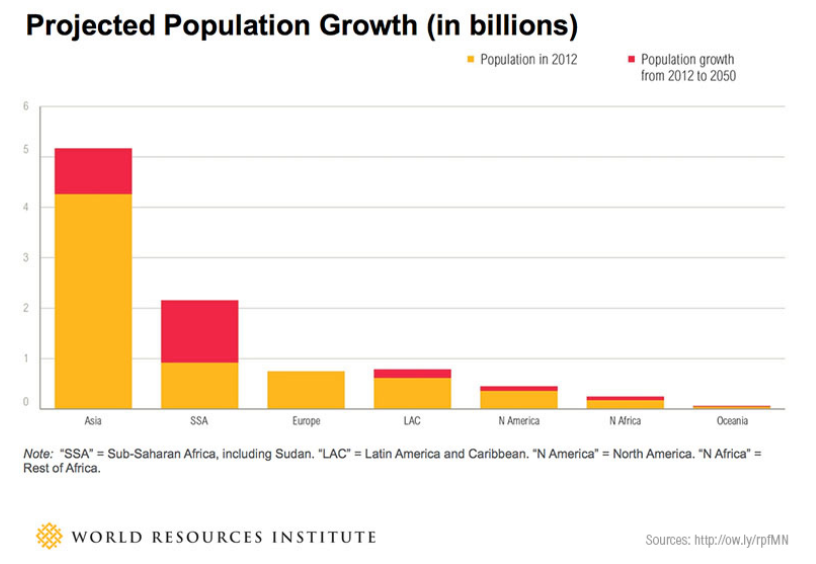

First among the problems is the ongoing global population explosion. The world’s population is projected to grow a further 37% by 2050. As the following chart from the World Resources Institute shows, most will be born in sub-Saharan Africa, a region whose population is expected to more than double by 2050.

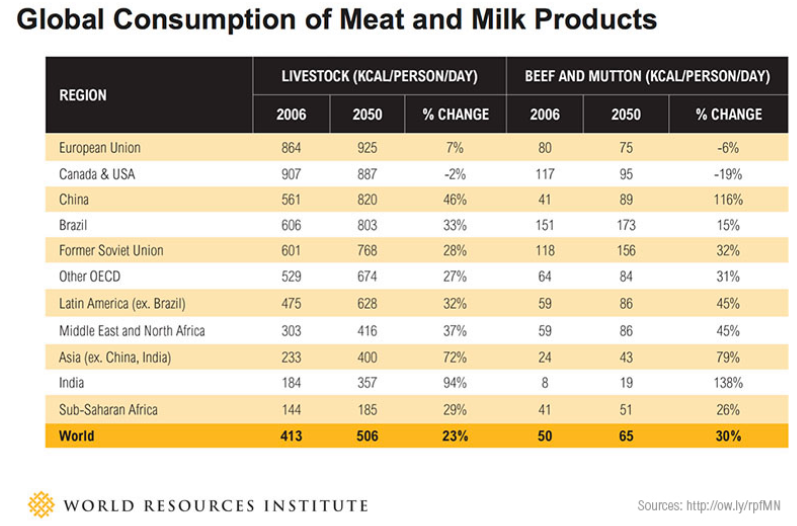

Next there is the problem of increasing meat and dairy consumption everywhere in the world except North America and Europe (where it is already quite high). If current trends continue, per capita world meat and milk consumption may be 20% to 30% higher by 2050. Meat and dairy products require vastly more land, energy, and water to produce than basic crops. That means that fewer calories are produced per acre of farmland when meat and dairy consumption rises.

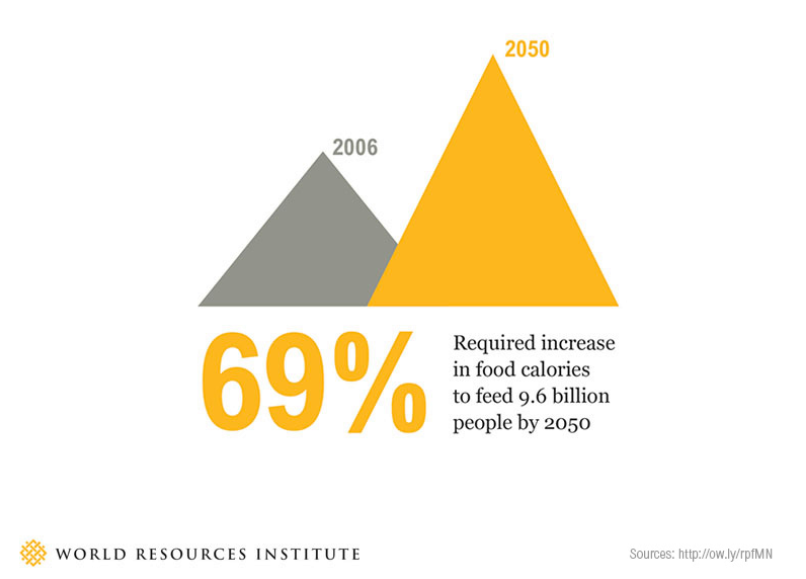

Unless dietary and population trends change, the world will need to produce 69% more calories by 2050 than are being produced today.

For those readers thinking about all the food that gets wasted between farm and fork, even if that waste were completely eliminated (and that’s highly unlikely), there would still be an approximately 30% shortfall between the calories needed in 2050 and the food produced today according to the World Resources Institute.

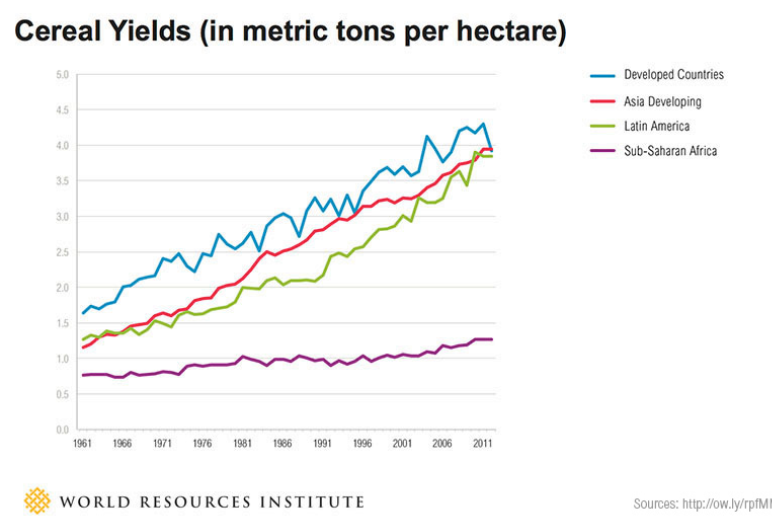

While cereal yields (the amount of cereal crop produced per acre planted) have been increasing since the 1960s, sub-Saharan Africa’s yields have consistently lagged the rest of the world. As the University of Nebraska-Lincoln study points out, even if this yield gap could be completely closed (also unlikely) it still wouldn’t meet the needs of sub-Saharan Africa’s surging population. This will create a significant regional caloric shortfall.

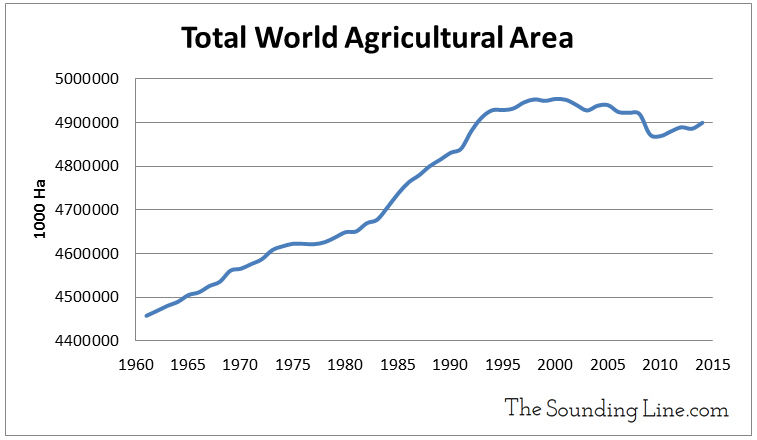

The world’s population is growing, per capita caloric consumption is project to rise, and eliminating food waste and improving yields are not enough to meet the food demands of the future. Therefore, the only way to satisfy caloric needs will be devoting more land to agriculture. Yet the following charts show that this may not be a simple task. Land devoted to all various agricultural purposes peaked in 2000 and is lower today than in 1993. It is difficult to know exactly why this is, but the fact that the surging food prices of the early to mid-2000s did not result in increasing agricultural land use suggests that additional land may no longer be available to farmers. Perhaps increasing populations are now out-competing agriculture for usage of land.

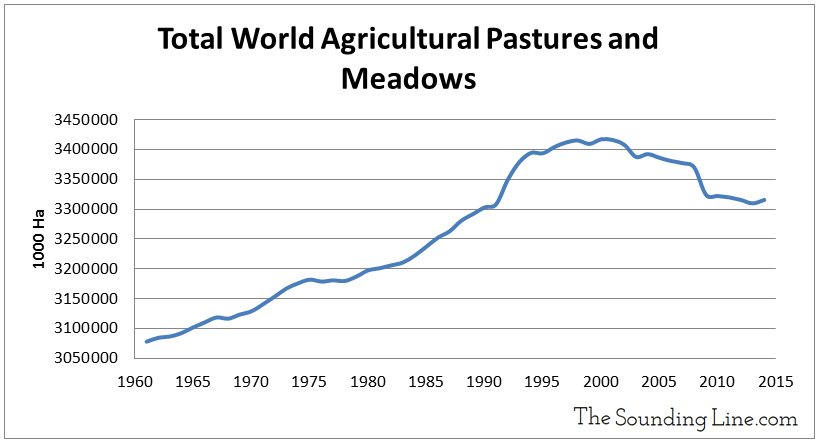

Among the various uses of agricultural land, the one which has seen the most rapid decline is also the largest by area: agricultural pastures and meadows. These are the lands used to graze livestock. The trend towards more ‘economic’ factory farms may be permitting much of what was once pasture land to be converted to non-agricultural purposes. It is not clear how that land can be returned to agricultural use if needed.

While no one knows exactly how these various factors will play out, it seems likely that agricultural supply will constrain demand and not the other way around. Unfortunately, increasing food prices may prove to be the mechanism by which markets keep dietary demands ‘balanced’ against constrained food production.

P.S. We have added email distribution for The Sounding Line. If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.