Taps Coogan – November 29th, 2021

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

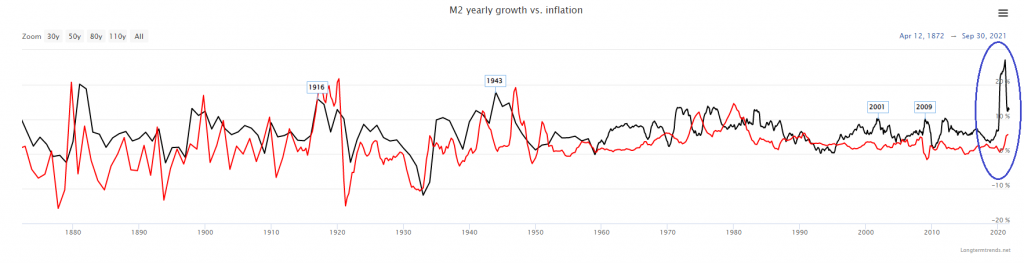

The following chart, from the wonderful website Long Term Trends, shows the relationship between the M2 money supply and CPI inflation since 1872, shortly after the Civil War.

The monetary response to Covid has created the fastest growth in the broad money supply in 150 years, more than the Spanish American War, WWI, the Spanish Flu, the Depression, the New Deal, WWII, Korea, the Great Society, Vietnam, the Cold War, 9/11, ZIRP, QE1, QE2, QE3, Not-QE, etc…

Over the last decade, a lot has been made of the fact that inflation has lagged money supply growth and, if you look hard enough (and forget how changes in consumption and inflation have led to inflation being increasingly under represented in the CPI metric), you can find that in the chart above. All else being equal, money creation that gets trapped at the Fed or in financial markets doesn’t cause as much inflation.

However, that’s missing the forest for the trees. The correlation between M2 money supply growth and CPI, albeit a bit sloppy, has held up for 150 years. When we’re talking about the nearly 30% money supply growth we hit last winter, the highest in 150 years, or the 13% right now, also one of the highest paces in 150 years, it’s foolhardy to think inflation is just going to peter out on its own in a couple months because the Fed slows the pace of accommodation to above QE3 levels.

To the contrary, all it’s going to take is a slight uptick in money velocity to send inflation up further from here. Exactly such an uptick may be brewing.

How long this economy can run hot enough to keep that inflationary impulse going if monetary policy begins to meaningfully tighten is highly questionable. However, don’t confuse that hypothetical ‘second order’ question of ‘how long’ with the issue of inflation’s trajectory in the first place.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

In the last three instances, 2001, 2009, 2011, the increase in money supply caused an immediate, direct, and concurrent decrease in the rate of inflation….. I don’t think that is just an under-representation – it’s clear and directional.