Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 17th of March 2016 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

The Federal Reserve met this week to hammer out the next steps for interest rates.

The consensus opinion held true that the Fed would not raise the Fed Funds Rate this week, or, it appears, any time until perhaps mid year.

With markets rallying, unemployment under 4.9%, and inflation beginning to tick up, the metrics certainly seem to have met the Fed’s criteria of a strengthening economy. The obvious question becomes how could they not raise rates?

The fact that the hint of a minuscule 0.25% increase in the Fed Funds Rate can move global markets is the best evidence that the central banks’ extremely accommodative policy has undermined the robustness of the global economy and supplanted free market fundamentals.

More important than the inability of the Fed to raise rates even 0.25%, may be the idea that an instrument as important as interest rates is being set with increasingly random and distractingly byzantine timing by a handful of academics using an ever shrinking handful of lagging ‘economic indicators.’

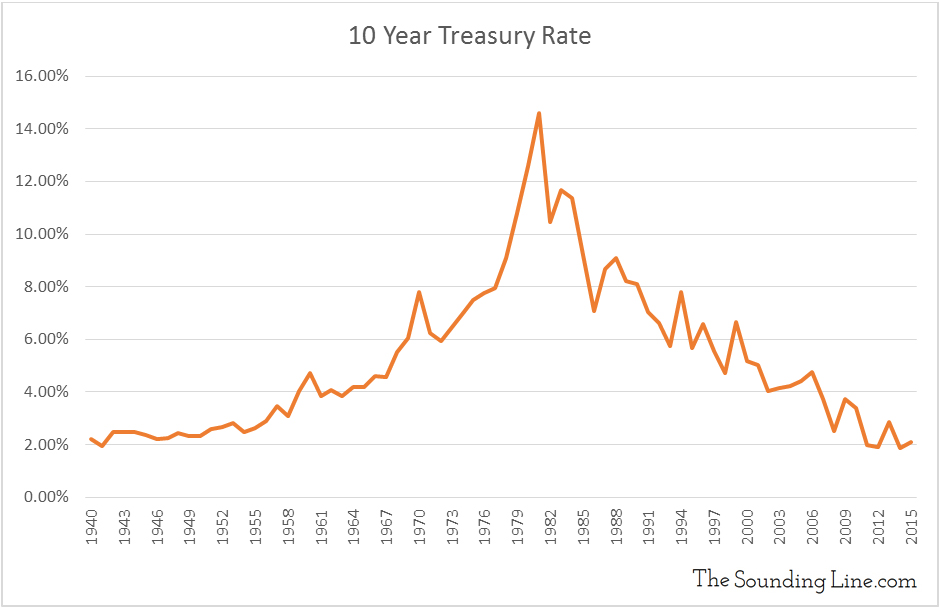

While the Fed can certainly manipulate interest rates higher or lower for quite some time, even they are subject to larger forces. Interest rate trends last for decades and persist through changes in Fed policy, recession, war and peace, and even monetary structures. The chart below shows 10-year treasury rates going back to 1940. Interest rates trended up from 1940 until 1981 and have been trending down since then.

While there is the possibility of an ill-advised incursion into negative rates in the U.S., interest rates are most likely near a bottom, whether the Fed likes it or not.

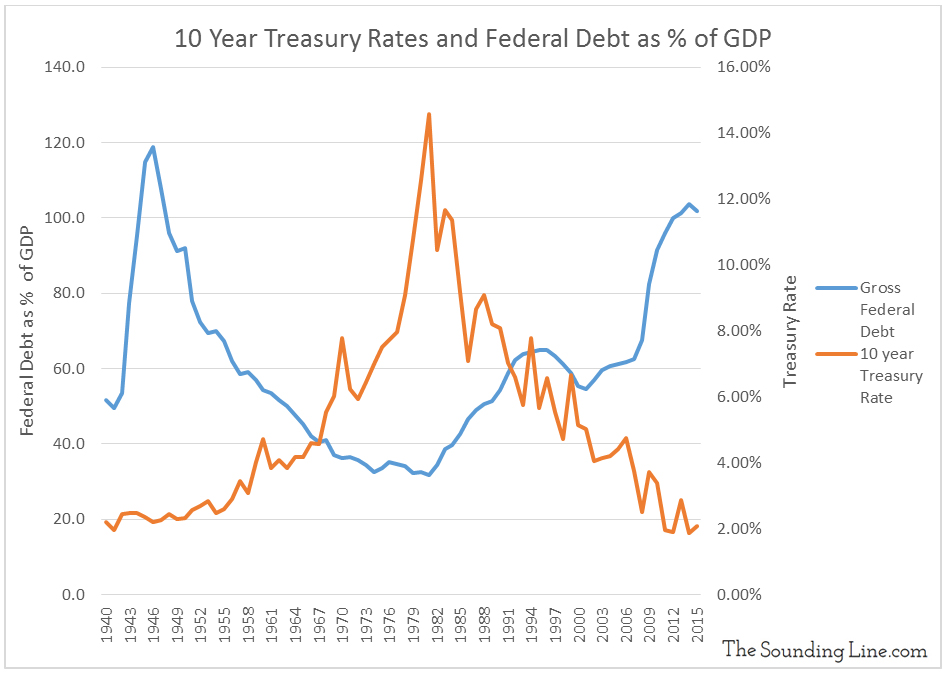

Given this longer term reality, we ask what rising interest rates would mean for the largest debtor in the history of the world, the U.S. Federal Government. The current U.S. Federal Debt, excluding unfunded liabilities, is over $19 trillion and over 100% of the nation’s GDP.

The amount of debt held by the U.S. has been inversely related to the interest rate on that debt. The debt was highest when interest rates were low in the 1940s, bottomed out exactly when interest rates peaked in 1981, and has been building again as interest rates have been falling.

In no small way, declining interest rates have enabled the Federal government to continue to borrow an ever greater amount of debt while keeping the cost of servicing that debt relatively low. The only other time in American history that the debt has been proportionally higher was during World War II. The large increase in spending and debt that occurred then was to support the war effort, and when the Allies emerged victorious, the U.S. was well positioned to reduce military expenditures, grow rapidly, and whittle down the debt.

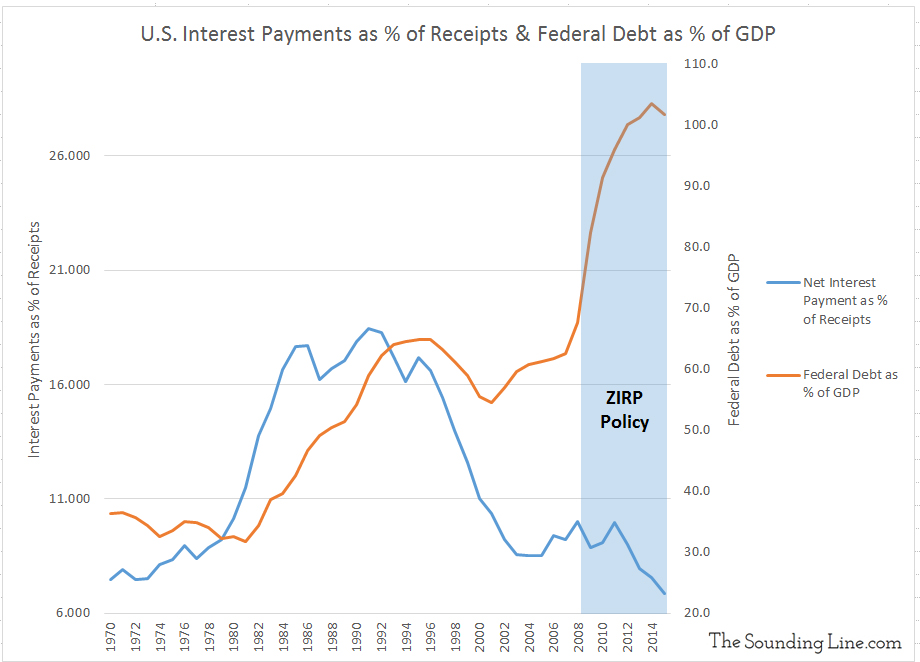

As the chart below shows, while the federal debt has exploded from less than 70% to over 100% of GDP during the period of Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP), interest payments on the debt as a percentage of Federal revenues have done the opposite and declined!

This is the direct result of the Fed suppressing interest rates and directly purchasing government debt through the Quantitative Easing (QE) programs.

This leads us to a final observation:

In the early 1990s, when 10-year Treasuries commanded statistically average and seemingly ‘normal’ interest rates of 6% and debt was approximately 60% of GDP, the U.S. was spending nearly 20% of revenues servicing its debt.

Today the debt is over 100% of GDP and entitlements are the largest and fastest growing element of U.S. federal spending. No nation can indefinitely sustain debt larger than its own GDP and entitlement programs are politically very difficult to cut. With persistently low GDP growth and an aging population, servicing our ballooning debt will become increasingly costly in a higher interest rate environment. Nothing good can come from this toxic mix.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.