Submitted by Tap Coogan on the 24th of April to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Once again, U.S. equity markets are near all-time high valuations. These high valuations are seen by many as an indication that the U.S. economy is healthy and that the Federal Reserve’s extremely accommodative monetary policy successfully created the conditions supportive of a broad based economic recovery from the 2008 recession.

In the case of a broad based economic recovery, one would expect that stock indices would rise in step with the aggregate financial performance of the underlying companies. In turn, one would expect that companies’ financial performance would improve in proportion with the aggregate investment that they make in the things that produce the goods and services that they sell. In other words, companies are making more money because they are growing and investing in the things that make the goods and services that they sell, thus their share prices rise.

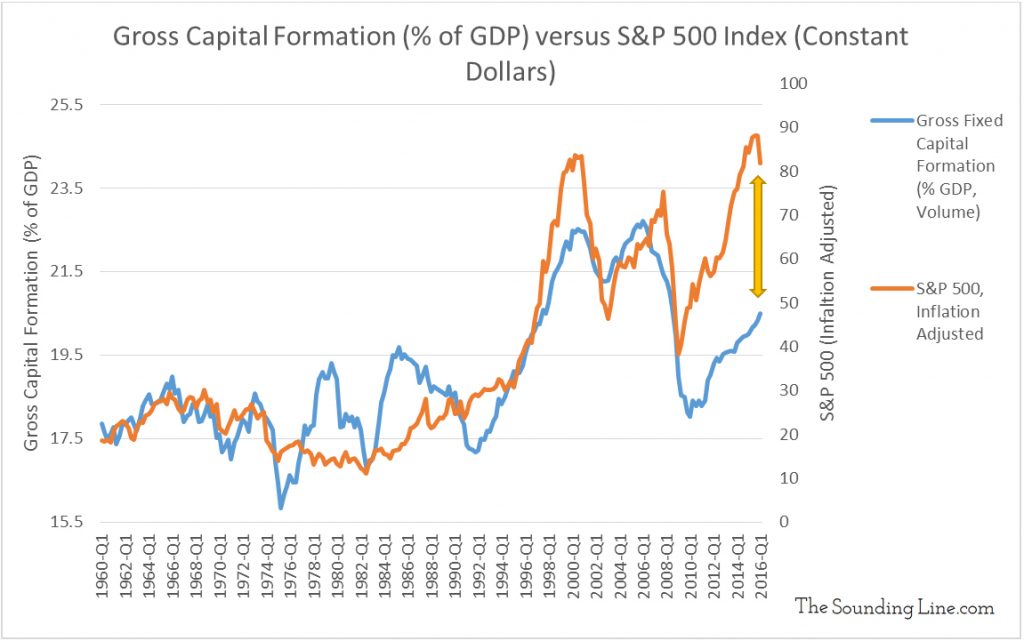

Historically, the relationship between equity market valuations and investments of this nature has held true. As a percentage of GDP, increasing investment in ‘fixed assets’ involved with the production of goods and services also known as ‘gross fixed capital formation’ (machines, factories, farms, software, airports, literary and artistic creations etc…) has happened in proportion with gains in stock indices.

That leads us to ask the following question:

Has investment in the things that produce goods and services kept pace with rising stock prices since 2008?

The chart below shows the relationship between US gross fixed capital formation as a percentage of GDP and the S&P 500 adjusted for inflation since 1960. While the S&P modestly out stripped fixed capital formation during the 2001 tech bubble and leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, the period since 2008 represents the largest and most sustained divergence on record between the S&P and fixed capital formation.

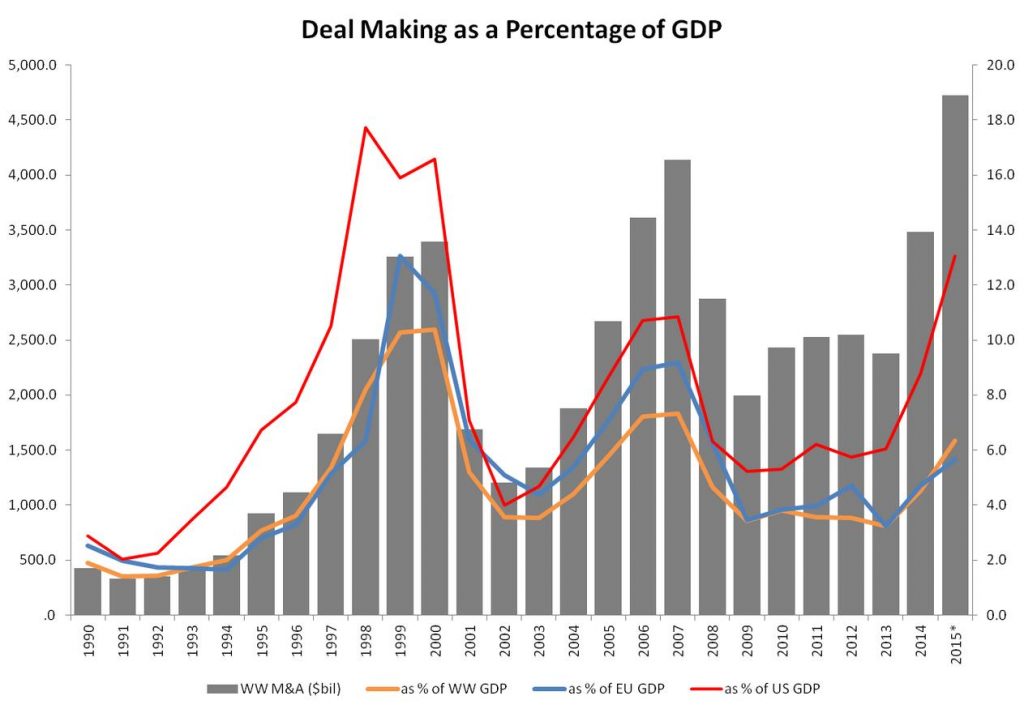

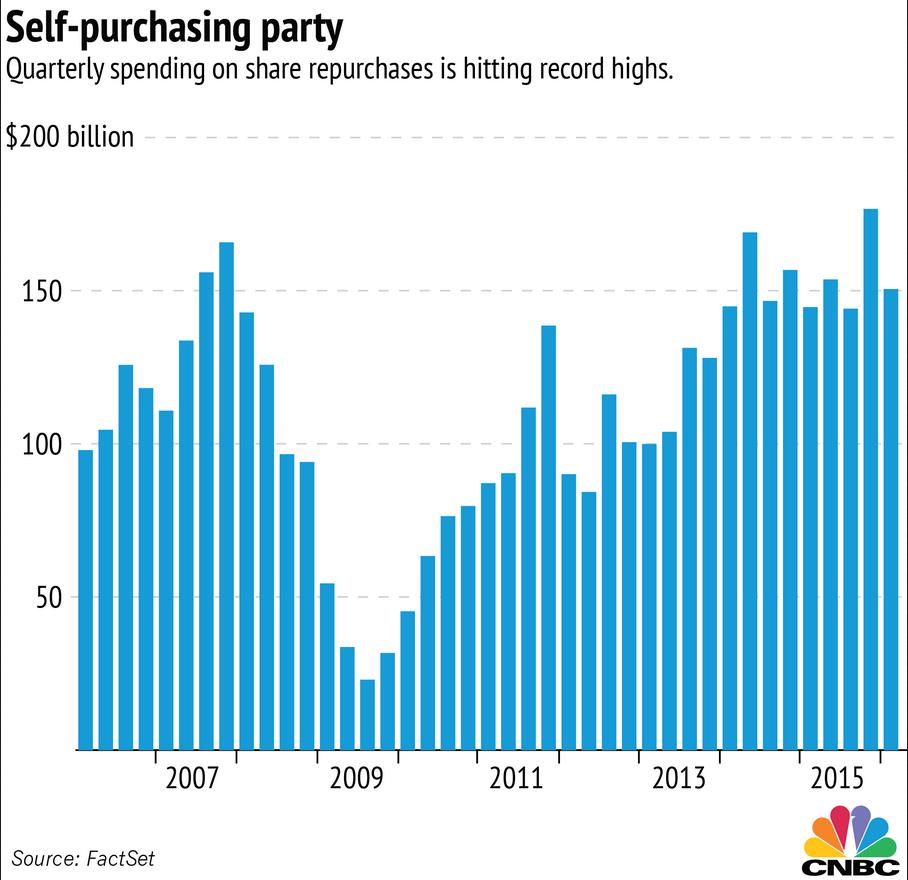

There is hardly better evidence that the Fed’s policies have only succeeded in driving stock prices higher, as opposed to creating a broad based underlying economic recovery. In actuality, stocks have risen because the Fed’s artificially low interest rates and quantitative easing programs have driven financial institutions and every manner of investor to invest in stocks in search of yields higher than the Fed’s fractional % offerings. Because this has created wealth for the comparatively few who are invested in stocks at the expense of the comparatively many who have savings accounts, pensions, and fixed income, there hasn’t been a proportional or broadly participated in recovery in consumption. Without commensurate growth in consumption there has been little need for companies to invest in new capital and capacity. Instead, companies have ‘invested’ in stock buybacks and mergers and acquisitions (M&A). All are similarly targeted at increasing equity valuations, not consumption of goods and services. As shown in the chart below, courtesy of Reuters (link here), world-wide M&A and corporate buy backs, courtesy of CNBC (link here), surged to their highest levels ever in 2015. This is quite literally the exemplification of a stock bubble.

And there it is, plain for all to see: a recovery in equity prices that has very little relationship to the actual engines of capitalism that fueled prior equity rises. This is a market built on speculation and financial jerry-rigging. In a later article we will explore the actual Corporate Earnings that have resulted from the post-recession period.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.