Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 10th of July 2019 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe.

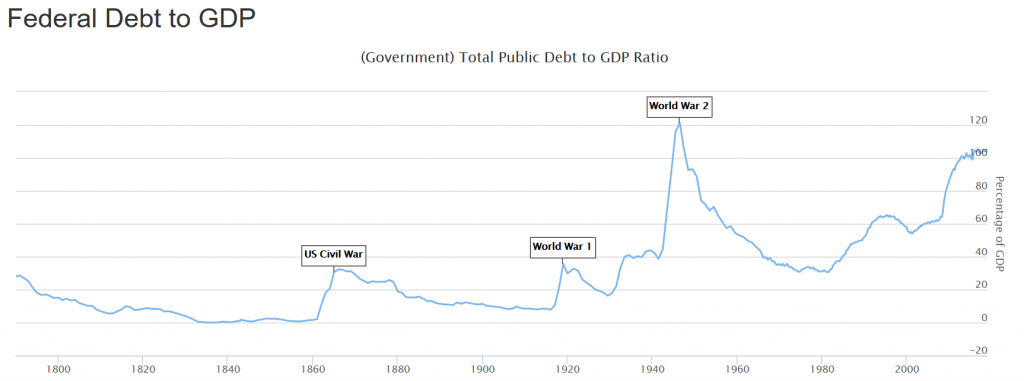

Here at The Sounding Line, we have documented the precipitous rise in the US national debt on many occasions.

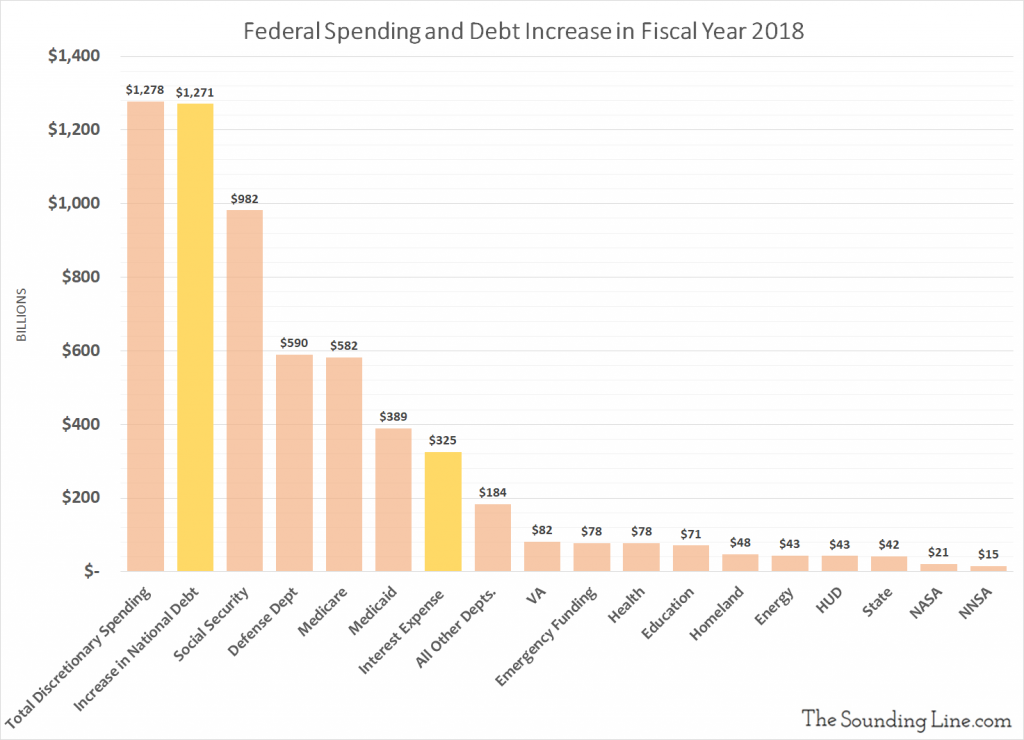

To put a fine point on the issue, last year’s increase in the national debt, $1.3 trillion, equaled the entire Congressional discretionary budget. The discretionary budget funds everything that the federal government does except for entitlement programs, servicing the national debt, and ’emergency’ spending. In other words, everything in the budgets that Congress debates would have to be eliminated to balance the real federal fiscal situation without raising taxes and cutting entitlements.

Meanwhile, the interest expense on the national debt is now the fastest growing element of government spending and is already larger than many major government programs.

Does The National Debt Actually Matter?

Despite what appears to be a perilous trend, there is considerable debate today as to whether the rise in the national debt is really a problem.

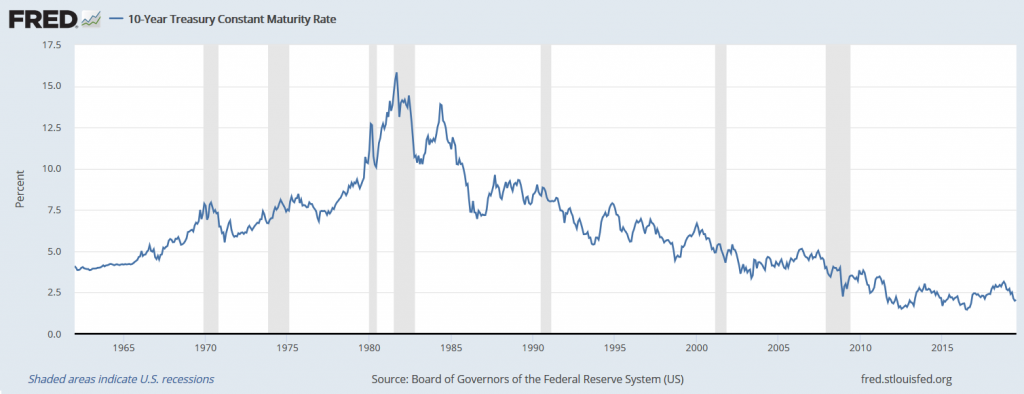

The argument against worrying about the national debt goes like this: Even if investors were to lose their appetite for US treasury debt, the primary dealer system guarantees that banks will pick up any slack in demand. If borrowing costs rise too high, the Fed can simply restart a treasury buying program, such as QE, and push rates back down. If necessary, the Fed could target the entire treasury yield curve and peg long term interest rates at low levels indefinitely, perhaps even negative levels. It wouldn’t take much imagination on the part of the Fed. Long term government bond yields are now negative in many developed economies.

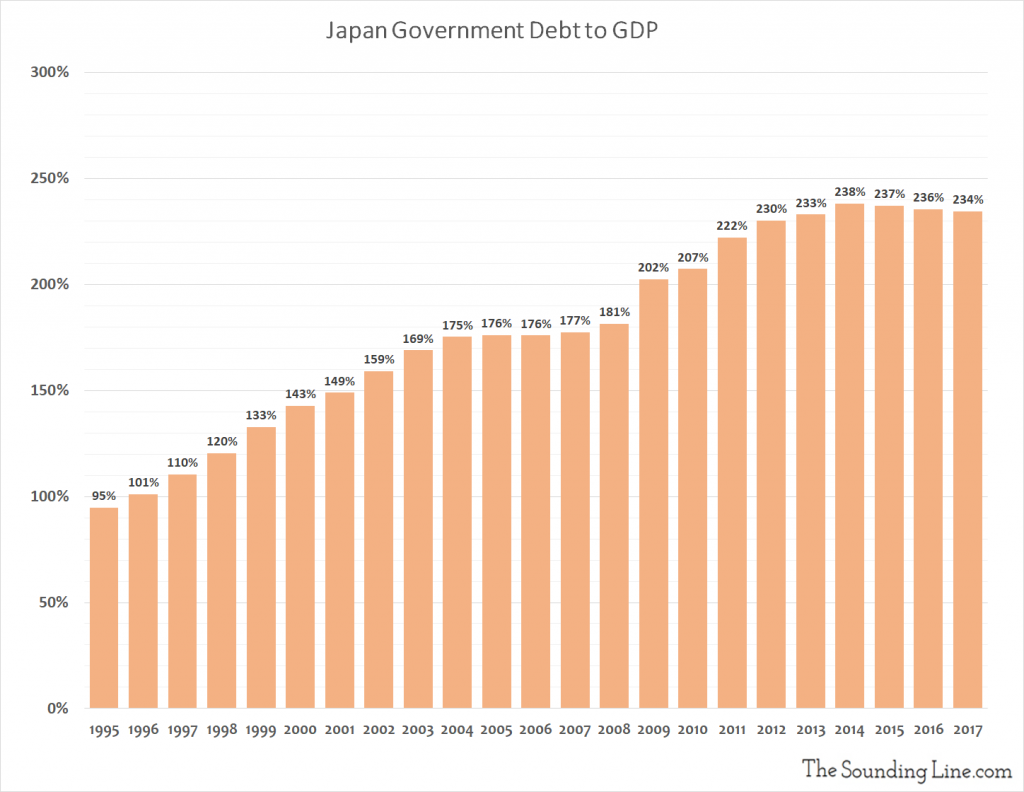

If government borrowing costs are negative and central banks are offering unlimited monetization, there is no obvious limit to how high the national debt could go. In Japan, where government borrowing costs are negative and the Bank of Japan buys virtually all net issuance of government debt, the national debt is over twice as large as in the US. No catastrophic debt crisis has occurred, nor has there been an inflationary crisis. In fact, Japan struggles with chronically low levels of inflation. Why couldn’t the US do the same as Japan? What’s to say that Japan’s debt couldn’t double yet again?

So goes the argument that the national debt really doesn’t matter. If the argument were true, governments and central banks have figured out a way to enable endless free government spending and borrowing. If true, governments could fund every pet project they ever dreamed of. There are now serious proposals to do so.

Of Course the National Debt Matters

Governments can spend and borrow endlessly only so long as they have unlimited access to cheap credit. Central banks can provide endless cheap credit only so long as inflation is low. Inflation will remain low only so long as economic growth remains anemic (and confidence in the monetary authorities remains high).

Japan and the Eurozone have been able to tolerate such an extended period of negative interest rates and debt monetization without producing inflation because it has corresponded with a period of negative growth (when measured in the world’s preeminent trade and reserve currency). In 2008, Japan’s GDP was $5.04 trillion. In 2018, it was $4.97 trillion. In 2008, the Eurozone’s GDP was $14.12 trillion. In 2018, it was $13.67 trillion.

If central bank policies ever succeeded in getting the economy to ‘run hot,’ they would no longer be able to provide the conditions necessary for governments to service the astronomical debts that they have already accumulated. It is simply the failure of monetary policy to create robust economic growth that is creating the perception that the national debt doesn’t matter.

Two things are likely to eventually happen. Either growth will remain sluggish forever and government spending and central bank asset purchasing will continue to rise to dominate what’s left of a withering economy, or inflationary pressures will eventually arrive. At that point, it will be far too late to do anything about the mountain of debt that’s already been accumulated. One outcome is a slow motion train wreck. The other is just a normal train wreck. We may end up getting a bit of both.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.