Taps Coogan – October 27th, 2020

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe.

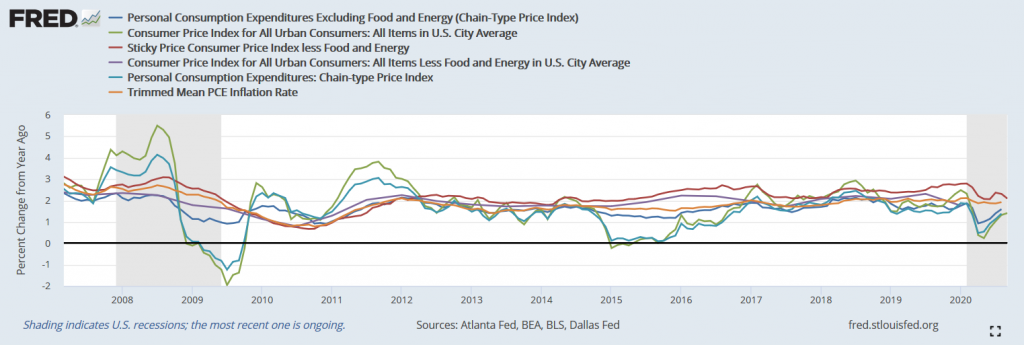

One of biggest riddles in our post-pandemic world is the outlook for the bond market. On one hand, you have the Fed promising to peg overnight interest rates at zero for years (but not go lower) while running a QE program twice the size of QE3. On the other hand, you have the federal government running multi-trillion dollar deficits, every mainstream measure of inflation already back over 1%, and the money supply growing at a pace more than double anything on record.

Basket of Inflation Measures

Money Supply Growth

Bond holders are already in a negative real rate environment with the potential for market-to-market loses if rates rise off of their historic lows. That could happen as a result of too much borrowing, too much printing, or just an old fashioned economic recovery. However, a rise in rates would tank historically indebted corporate borrowers and explode the interest expense on the national debt, making a double dip recession a real possibility.

What’s a central planner to do? Well, the last time the US faced massive budget deficits and the need to keep interest rates low across the yield curve was World War II. The federal government was just as indebted as today, running budget deficits just as big as today, and needed to keep borrowing costs low just like today (though for a very different reason). So what did the Fed do? Instead of just pegging overnight rates, they pegged 10-year treasury rates at roughly 2.5% in 1942 and kept them there until 1951. They bought however much treasury debt was needed to keep long term treasury yields from rising for nearly a decade.

How did it end? CPI inflation hit nearly 10% in early 1951, forcing the Fed to abandon the yield curve fix. Fortunately, the US could massively cut back on military spending after the war and enjoyed rapid economic growth which allowed monetary policy and inflation to normalize for the remainder of the 1950s and 1960s.

Unfortunately, today’s deficits are entirely different. As we have pointed out on numerous occasions, Congress could eliminate the entire military and not halt the growth in the national debt. In fact, Congress could eliminate all government spending except for entitlement programs, off-budget spending, and the interest on the national debt and not halt the growth in the national debt. All of that was true before Covid and it is doubly true now.

If the US has any hope of avoiding very bad outcomes like stagflation, it rests on repeating something like the post-war boom: outgrowing our problems through a big increase in nominal GDP growth and a cut in deficit spending. The task will be even harder this time, but one can hope.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.