Taps Coogan: June 22nd, 2022

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

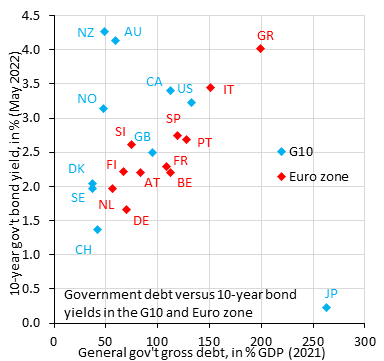

The following chart, from IFF Chief Economist Robin Brooks, shows the relationship between government debt-to-GDP ratio and the interest rates on 10-year government bonds for the world’s developed economies.

The takeaway of the chart above is how extreme of an outlier Japan is (bottom righthand corner). Not only does it have far and away the highest debt levels, it also has by far the lowest sovereign yields.

Japan represents the archetypal ‘developed’ economy. It was the first modern economy to see its real-estate bubble peak (early 1990s) and then to see its workforce start shrinking, followed by the rest of its population. It was the first country to hit zero interest rates and the first to try negative rates. It was the first to implement quantitative easing (QE) and the first to use QE to buy stocks. It is the most indebted economy in the world and the only major economy still using overt yield curve control.

For twenty years, observers have speculated about how the Japanese experiment would end. The general feeling, often shared here at The Sounding Line, was that rising inflation would someday force the Bank of Japan to choose between prioritizing the stability of its currency at the expense of its bond market bubble, or vice versa, with both choices requiring ever more ‘doubling down.’

It appears that exactly such a situation is now unfolding. Last week, the Bank of Japan was forced into doing the most quantitative easing in its history in order to defend its 0.25% cap on 10-year yields, just over $81 billion of QE in one week, as the following chart from Bloomberg highlights.

The result of massively accelerating QE as inflation ticks up to 2.4% in Japan (a high reading for Japan), is that the Yen has lost about a quarter of its value versus the US Dollar in the last six months. The Bank of Japan may very well feel that an inflation reading of 2.4% is tolerable and that a decline in the Yen of such a magnitude is also tolerable precisely because it hasn’t produced more inflation. However, how far will the Bank of Japan have to go?

To take the extreme example, if Japan intends to enforce yield curve control to the bitter end and has to buy its entire sovereign debt market, back of the envelope math says they have to do another roughly $8 trillion of QE. Scaled for GDP, that would be the equivalent of the FED doing $34 trillion of QE in the US.

Of course, the easiest solution to the predicament of inflation pressuring sovereign borrowing costs is balanced budgets. If Japan balanced its budget, yields on Japanese government debt could spike to the moon and it wouldn’t matter much because they wouldn’t be borrowing at the rate. On top of that, well thought through reductions in government spending would reduce excessive demand, hold rates lower, and reduce inflationary pressures in a targeted way while allowing central banks to reduce the monetary base without diverting investor capital from productive investments and into sovereign debt markets.

Don’t hold your breath.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

If the much of the borrowing the Japanese gov’t is doing is to fund things like healthcare and old-age pensions, the likelihood of those services being cut is nil given Japan’s demography, since it would be political suicide. Plus, a belligerent China is forcing Japan to double it’s defense expenditures.

It makes sense that Japan is perhaps the most advanced country in robotics development, and why so much of their industrial plant has been exported to the U.S. and elsewhere.

excellent summary. thx