Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 2nd of May 2016 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Chris Hambone of ‘Hambone’s Stuff’ recently published an excellent article (here) that discusses the implications of declining growth rates in working age populations around the world.

As that article highlighted, the topic of declining population growth rates is overlooked as an explanation for today’s persistent global economic malaise.

In order to better understand the implications that a dwindling working force will have for the world’s aging economies, Japan, as it so often does, provides a perfect case study.

Japan is not only the most elderly country in the world, with nearly a third of the population over 65, but Japan experienced a negative 0.74% population growth rate for the first time in 2015. The overall Japanese population has fallen by over 1 million people from its high of 126 million people, and is on pace to fall by another 20 million people by 2050.

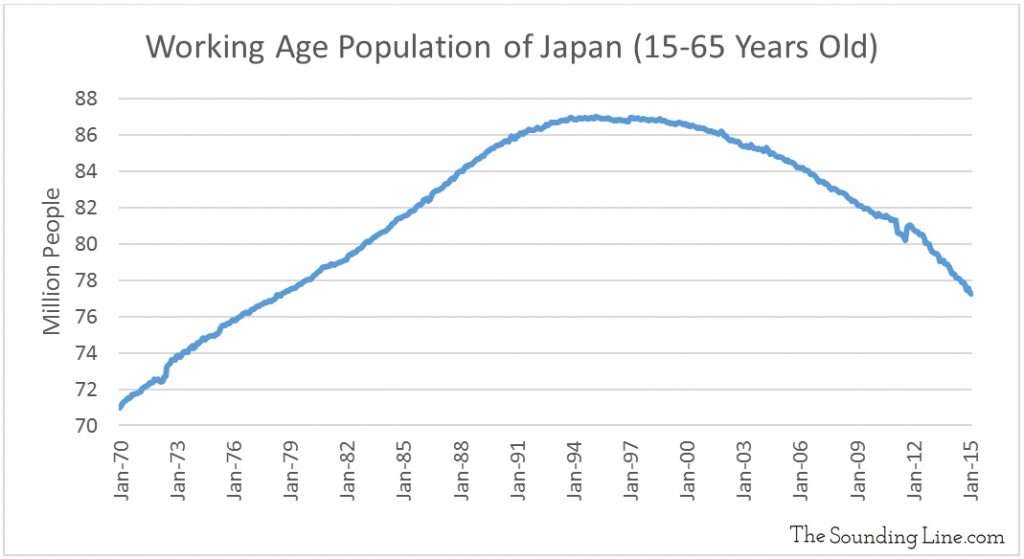

While the total Japanese population is just beginning to decline, the working age Japanese population (15-65 years old) started peaking way back in 1991, and has declined 11% since from its all-time high of 87 million in 1995.

It is no coincidence that just as its working age population was cresting in 1991, Japan entered into what is often termed as the ‘lost decade’. The ‘lost decade’ (which is actually 24 years long and still running) refers to the period of extremely slow and often negative economic growth that has persisted in Japan from 1991 until today. Remarkably, nominal Japanese GDP is 14% lower today than in 1995 and nominal wages are lower than in 1991.

For countries like Japan which are faced with the dilemma of a shrinking workforce, there are essentially three ways to maintain or grow their economy:

- Grow the workforce

- Increase the productivity of the remaining workforce

- Increase the rate of consumption of the population

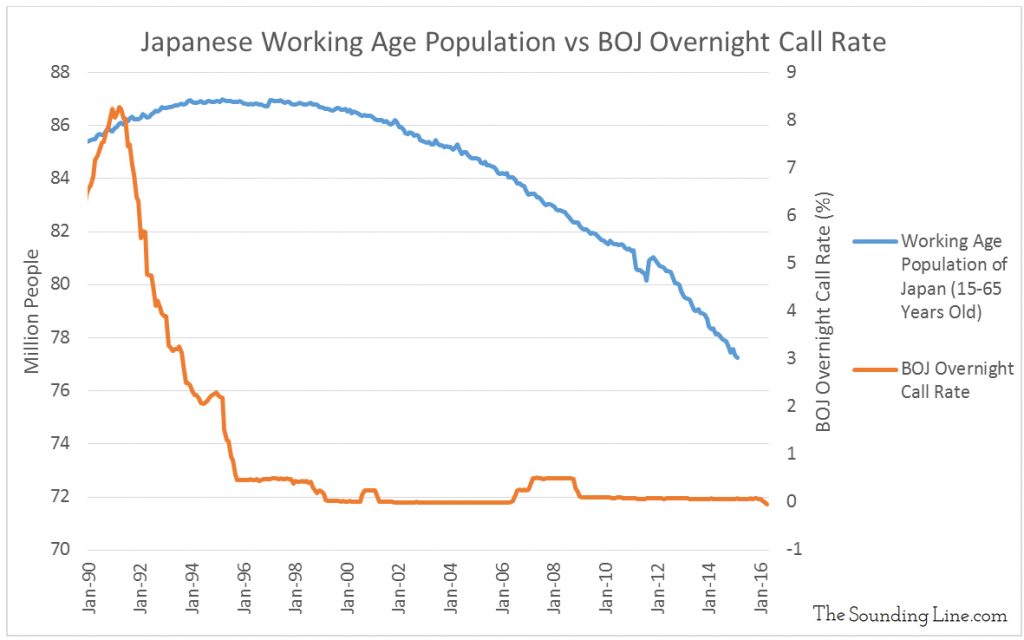

Consciously or not, Japan appears to have chosen the last option. 1991 marked the beginning of Japan’s ongoing experiment with zero interest rate policy (now negative interest rate) and quantitative easing. These tools are aimed at spurning savings and spurring consumption. It is a little known fact that Japan was the first country to experiment with quantitative easing in the early 2000s.

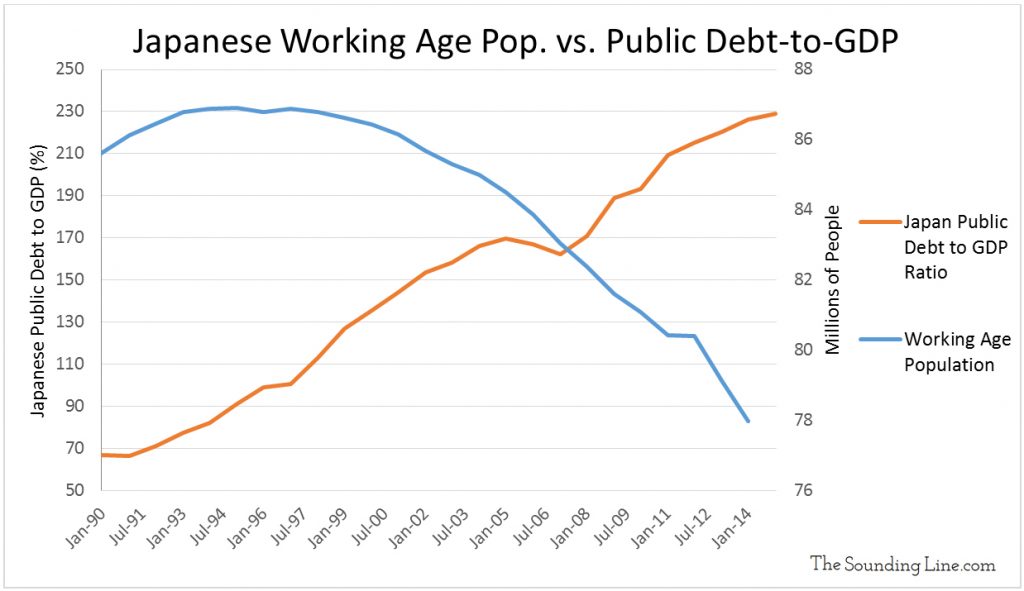

Unfortunately for Japan, it is productivity that creates the wealth that enables sustained consumption. Increasing consumption without first increasing productivity and/or size of the workforce is unachievable without increasingly unsustainable levels of debt.

Japan has demonstrably failed to meaningfully increase its productivity and as a result the nominal GDP per capita is also lower today than in 1995. Japan’s central planners have chosen the path of debt and the result is the highest public debt to GDP ratio of any country in the world.

Because Japan was unable to sufficiently increase its productivity, it has been forced to choose between spiraling debt or a shrinking economy. It has managed to achieve both.

While this is all very bad news for Japan, nearly all developed western countries are in similar situations.

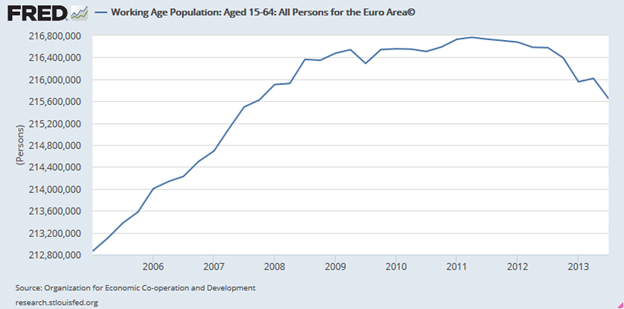

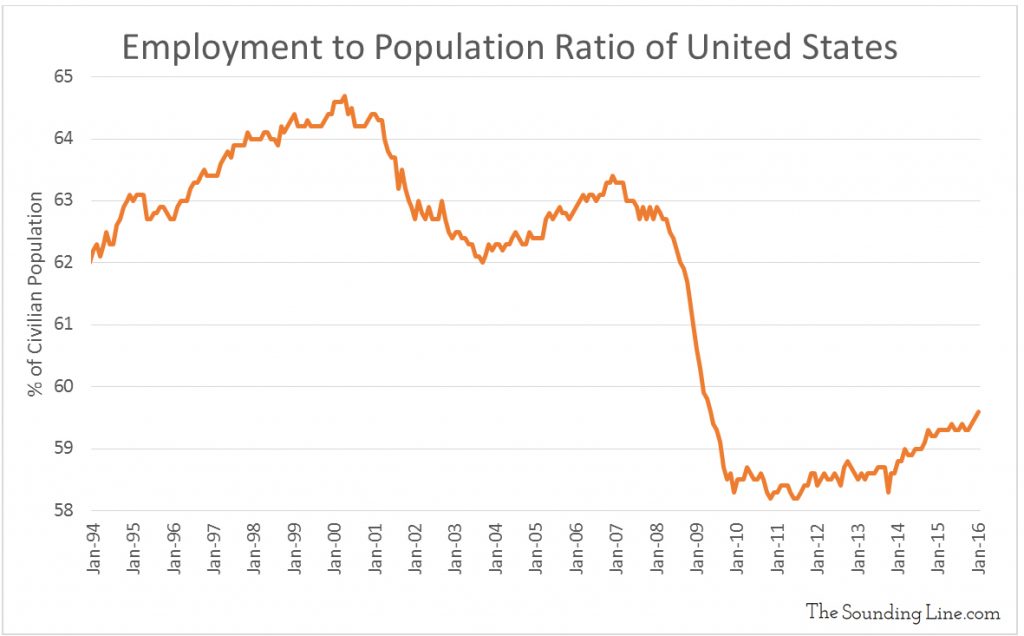

The working age population of the Eurozone peaked in 2011 and while the US working age population is still increasing, those actually working as a percentage of the population peaked in 2000.

This all paints a surprisingly simple picture. If a country’s work force gets smaller, so does its economy, unless great increases in productivity or debt driven consumption occur. Central banks world-wide have attempted to incentivize consumption by suppressing interest rates, in effect choosing the path of debt, instead of looking for other less financial and more innovation and production oriented ways to boost productivity. The result has been the largest global accumulation of debt in history. All of this increasingly diverts funds from productive ends to the servicing of debt, compounding problems further. While central banks should be criticized for implementing such unsustainable policies, we should hardly be surprised that they tried this path exclusively. Central Banks are after all owned by banks, run by bankers, and are essentially an unelected “cartel” of banks. Banks are in the business of creating loans, that is what they know best and exactly what they have chosen to do. The true problem today is the enormously outsized role that banks play in running the global economy.

Perhaps it is time to pass the reins to an group that knows about manufacturing, innovation, productivity and all things related that actually create the lion’s share of global prosperity: industry.

P.S. We have added email distribution for The Sounding Line. If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.