Submitted by Taps Coogan on the June 9th 2016 to The Sounding Line

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Over the last 15 years the world has experienced some of the greatest overvaluations in modern times. Extraordinary valuations in real estate and stock markets have rocked many nations to their core. Today, when we survey the global economy for asset “bubbles” there are many candidates. For example, steadily rising US student debt levels have combined with already high and rapidly growing payment delinquencies as discussed here. There are other “bubbles” to be found, including, some would argue, a return to certain real estate market overvaluations. Though today’s private sector “bubbles” are troubling, they are nothing as compared to that which we experienced just a decade ago. However, there is one “bubble” whose reality is unquestionable. Its magnitude is unmatched in human history, and its ability to be resolved through a “soft landing” is mathematically implausible at best. Reality can bite and this reality has been growing its teeth for decades.

The most serious bubble today is in government debt.

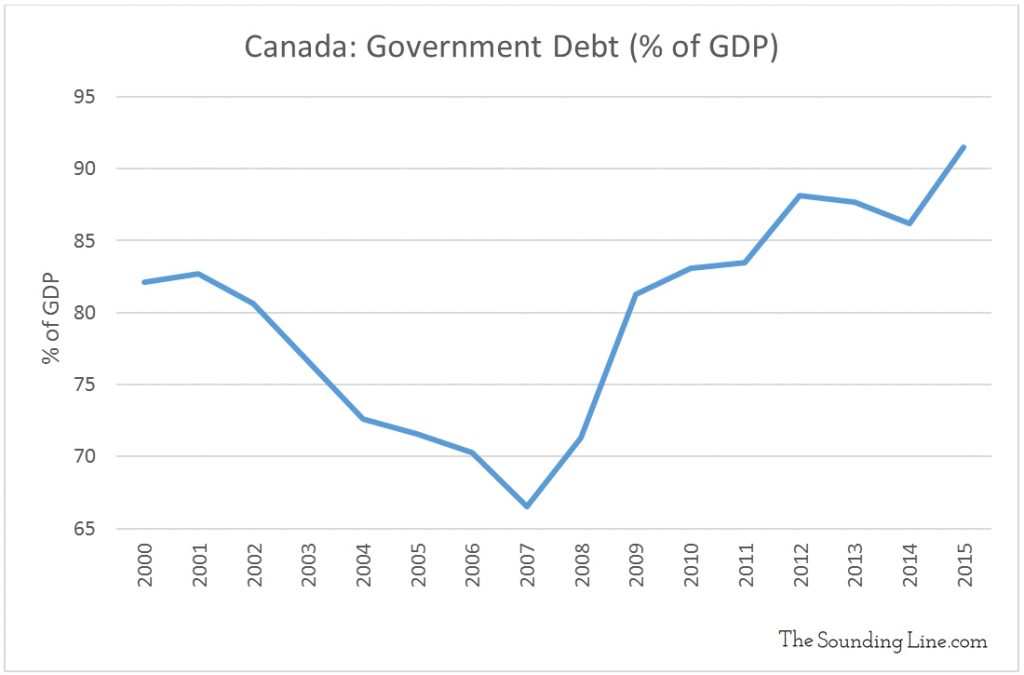

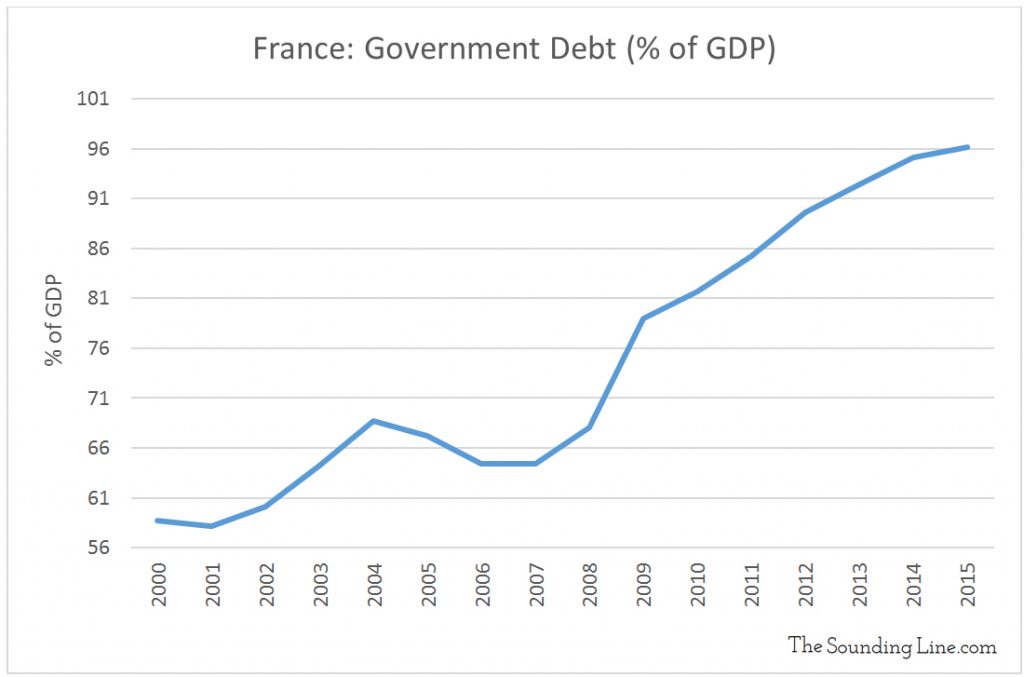

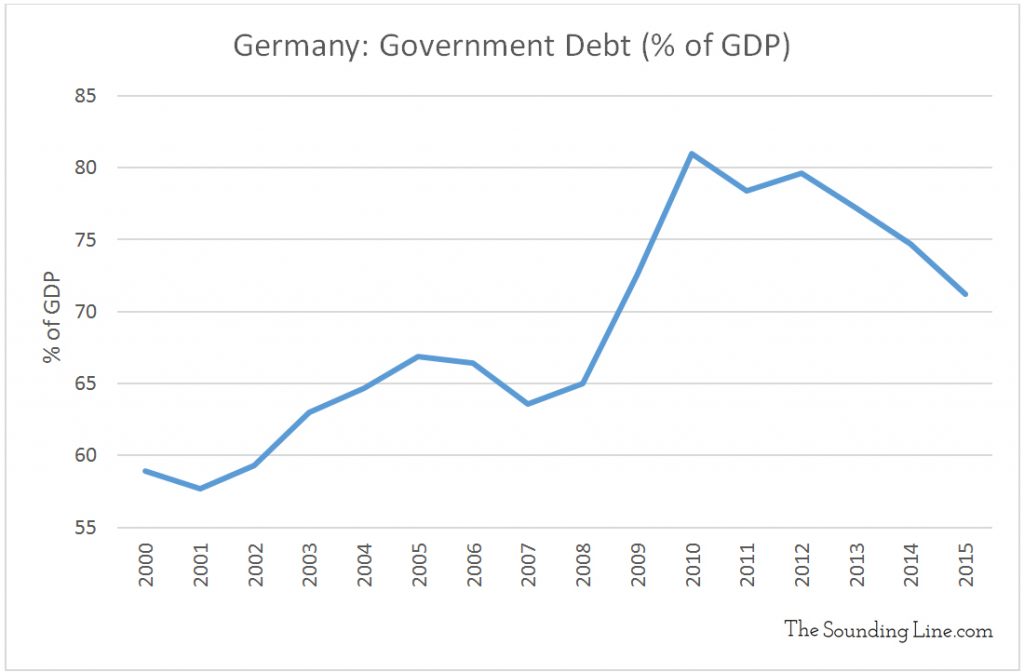

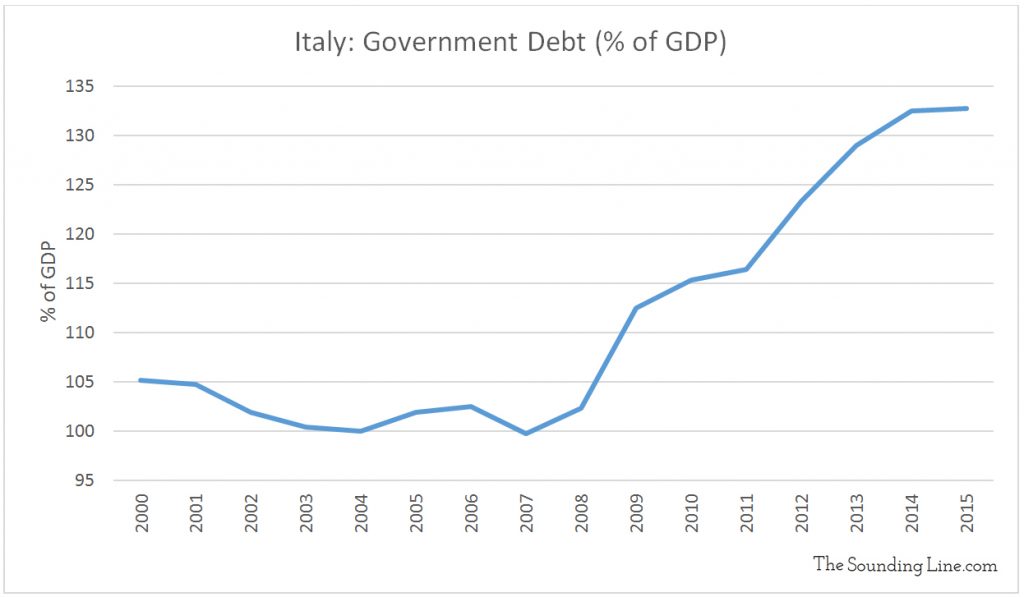

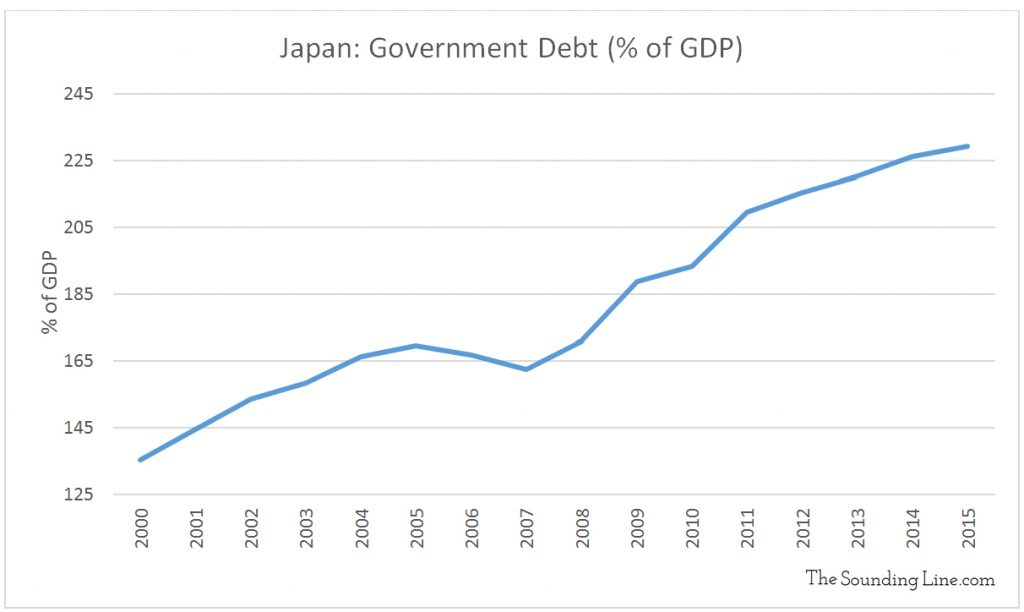

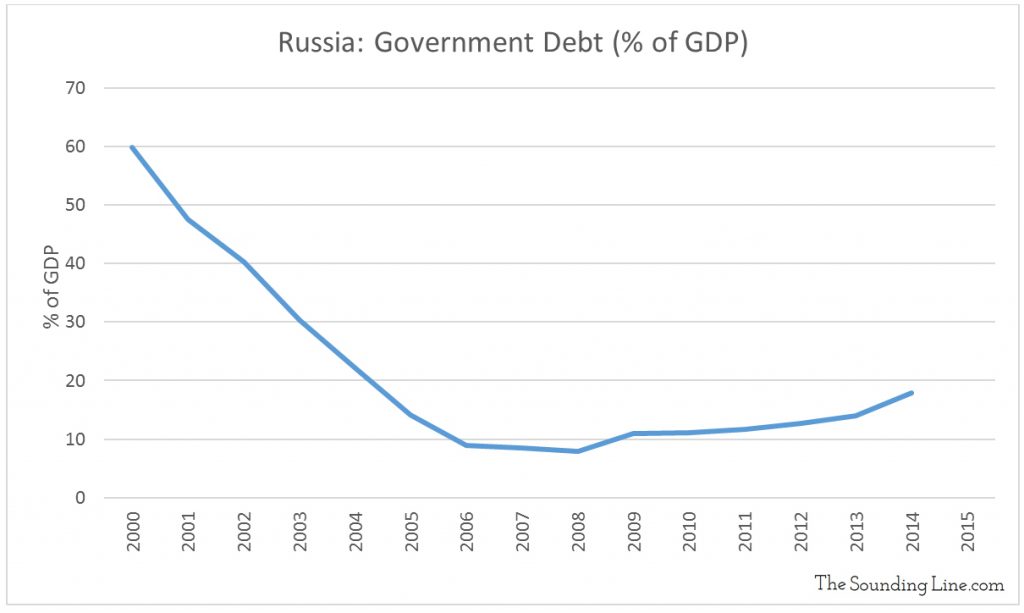

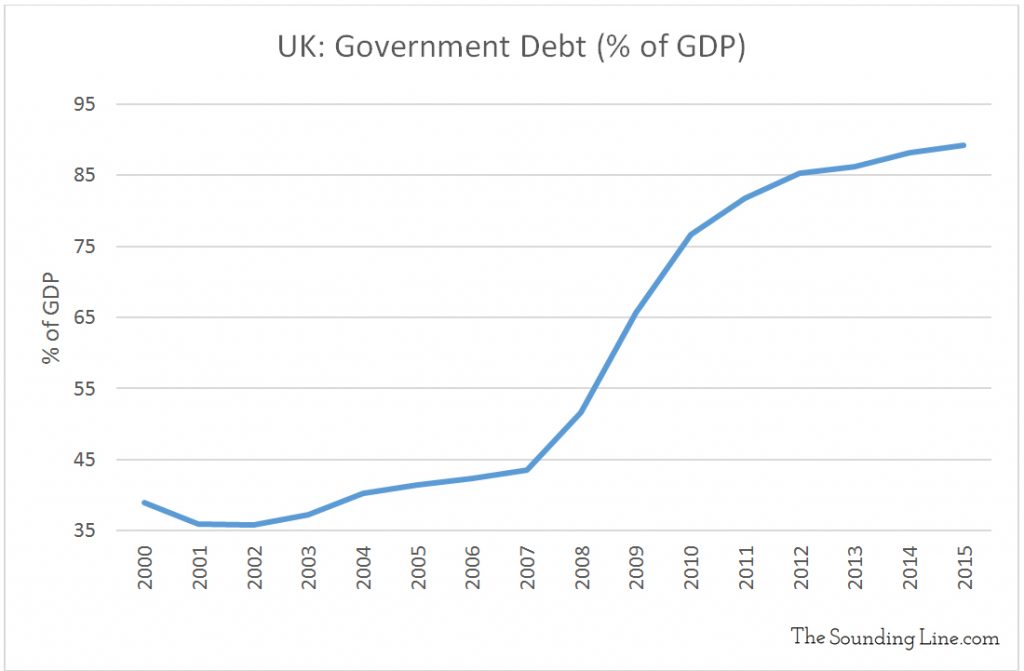

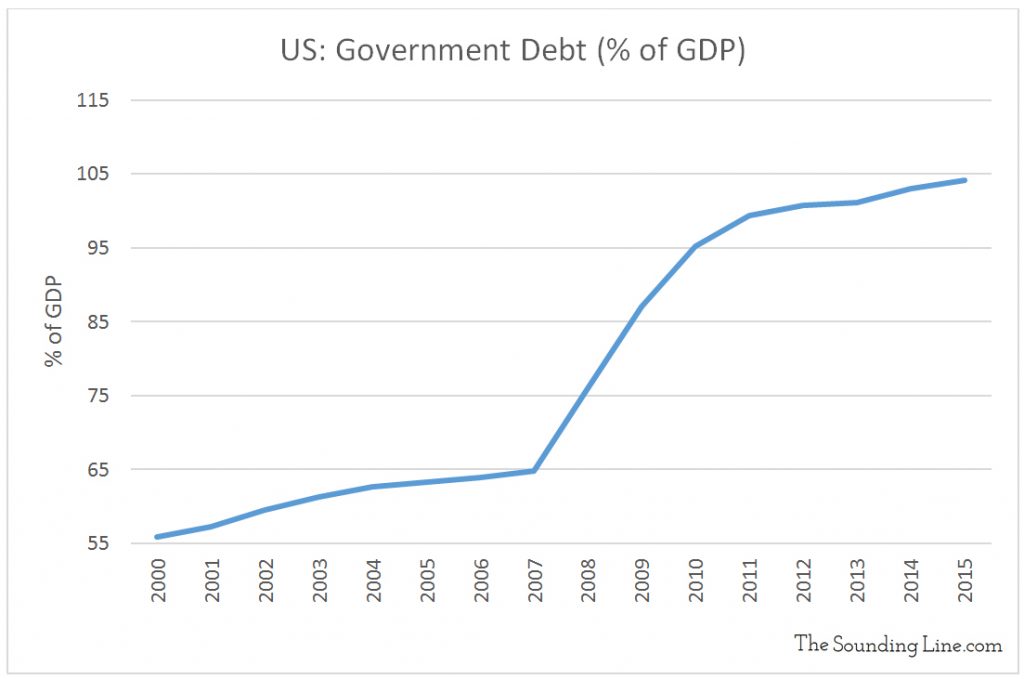

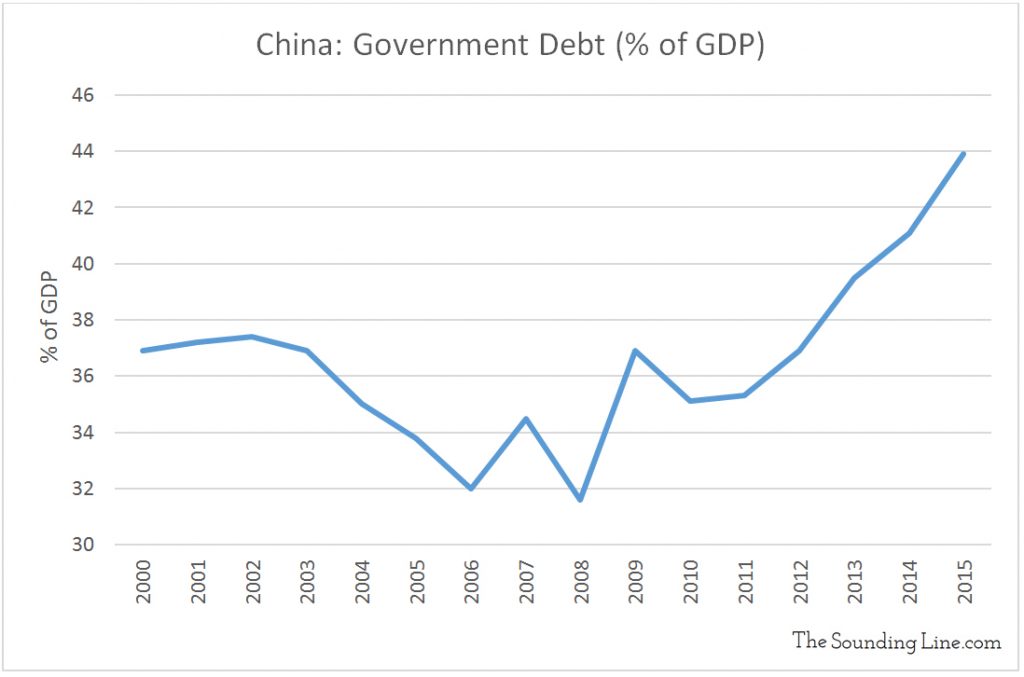

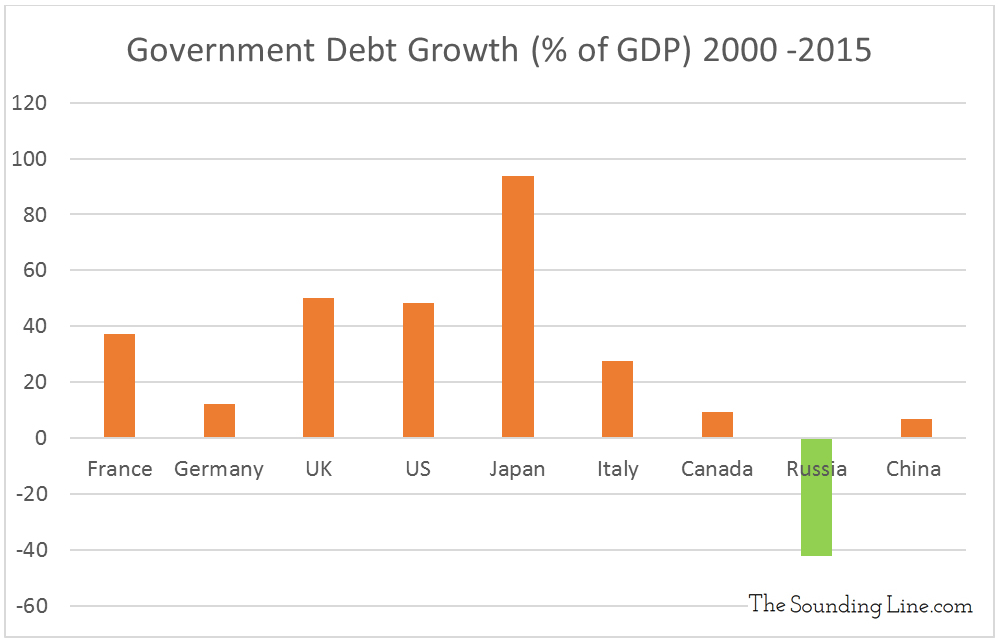

The charts below show the growth in government debt as a percentage of GDP for the each member of the G8 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, UK, US, and China).

The only country which has reduced its debt levels since 2000 is Russia.

Politicians claim that increasing public spending boosts the economy. Yet, for the last 15 years, increases in public spending (which have overwhelmingly been paid for by debt) have led to economic growth rates far lower than the growth of debt. This is the exemplification of an unsustainable and dangerous “bubble.” Where will the growth come from to pay off the debt if the enormous increases in debt have resulted in economic growth rates slower than the growth in the debt itself?

The answer is that the necessary growth rates are achievable.

Here are a few alarming figures that demonstrate why:

The weighted average maturity of outstanding marketable US treasury debt is approximately 68 months or five and a half years (here). The current outstanding federal debt is about $19.2 trillion (here). That means that the US government will need to repay half of all outstanding government, or $9.6 trillion, within the next five and a half years (half of all outstanding debt matures before and half after five and a half years).

In the ideal case that the $9.6 trillion debt repayments could be spread evenly between the 5.5 years, the US government would have to spend $1.7 trillion or about 10% of 2015 GDP and over 50% of total 2015 federal tax receipts every year for the next five and a half years just to pay off 50% of the debt already accumulated.

In 2015 the government spent 6.8% of federal tax receipts servicing existing debt. Going from spending 6.8% of federal tax receipts in 2015 to over 50% of 2015 receipts each year from 2015 to 2020 would require either massive reductions in spending or dramatic increases in taxes and debt. For those who think that it is possible to just outgrow the debt, consider that from 2000 to 2015 the US government debt grew at an average annual rate of more than twice that of the US economy. To outgrow the debt growth would require sustained GDP growth of over 8.6% per year. This assumes no further increases to the rate of growth in debt beyond the 2000-2015 average rate, and given the burden of servicing existing debt, this is a highly improbable assumption.

China, the fastest growing large economy in the world, only expects 6.5% – 7% annual GDP growth in the coming years. The World Bank expects the US GDP to grow by 1.9% in 2016, a far cry from the 8.6% needed.

Despite the Treasury’s disingenuous projections that the US will somehow reform decades of politically sacred deficit spending and enjoy surging growth for the foreseeable future (here), it is clear that a repayment of existing US Federal debt can only be accomplished through increasing amounts of new debt and seeking other sources of revenue such as higher taxes. Higher taxes will dampen economic growth and compound problems further.

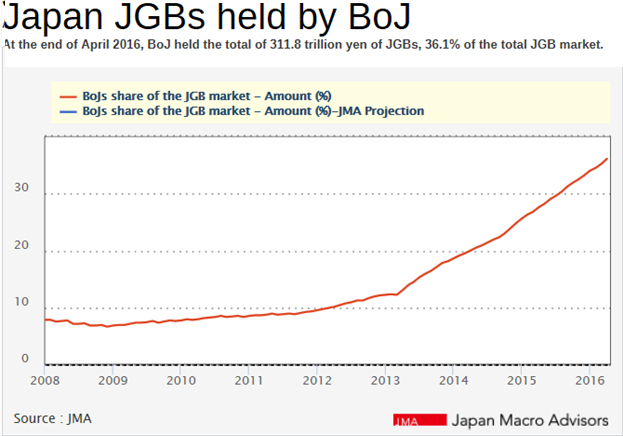

Lest one think that the problems are restricted to the US, fellow G8 member Japan has a debt to GDP ratio more than twice that of the US. Japan’s GDP is smaller than in 1995 and it is already projected to be spending 43% of tax receipts servicing its debt (here).

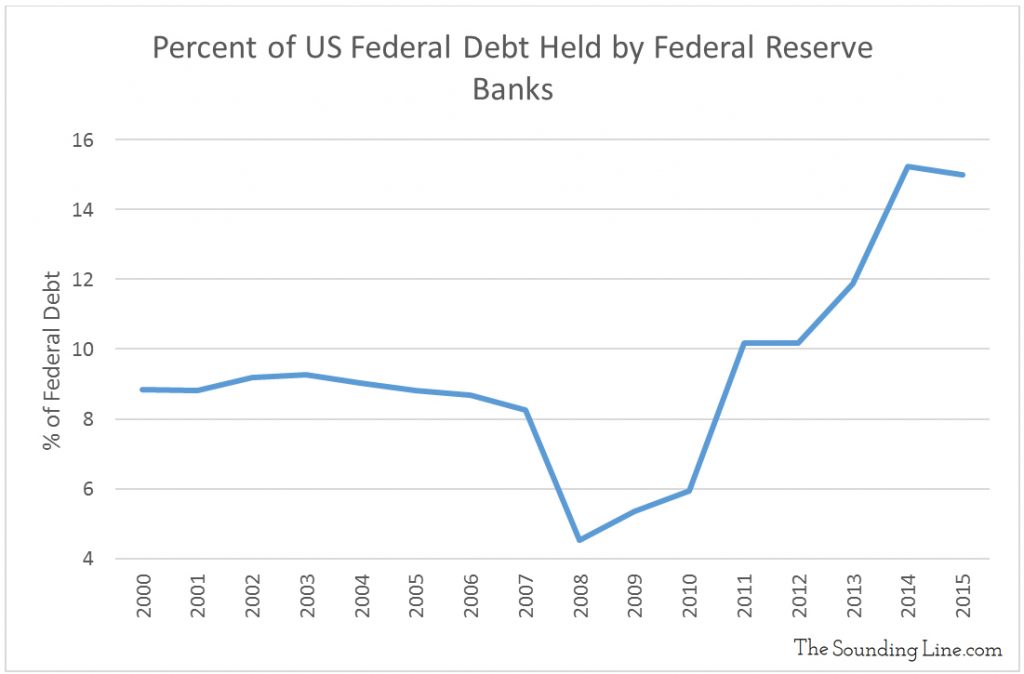

When borrowers are forced to take on new debt to pay for existing debt, no economic gain can be achieved by the new debt, and default becomes inevitable. Most of the developed world is now in this position; without dramatic cuts to spending, existing debt can only be paid off with new debt. Normally this financial peril would cause interest rates to spike, ensuring default. It is a no wonder that central banks the world over have turned to huge quantitative easing programs to suppress interest rates and directly monetize government debts.

The combination of rising debts and rising delinquency rates was the red flag that the 2008 housing crisis was inevitable. Today, the percentage of new debt that must be monetized by central banks to keep interest rates low enough to prevent a debt crisis can be viewed as a parallel to the delinquency rate on housing debt. As the charts below show, the percentage of existing government debt (known as Japanese Government Bonds or JGB in Japan) owned by the Fed and the Bank of Japan (BOJ) have been growing and stand at 15% and 36% respectively.

This issue is not limited to just the US, Japan, the G8, or China but exists in nearly every developed economy in the world. When one realizes that banks use government securities as their ‘reserve quality’ assets, it is clear that this is the largest and most dangerous “bubble” in human history. The probability that the world will enjoy a miraculous global growth spurt that is sustained for years despite implementing austerity, and without resulting in significant inflation, is far, far lower than the probability of some governments defaulting on their enormous debts in the near future. Either way, reality bites.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.