Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 4th of October 2017 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

As the leadership of Catalonia prepares to declare independence from Spain following its recent independence referendum, it is worth examining where Catalonia and Spain would stand economically as independent nations.

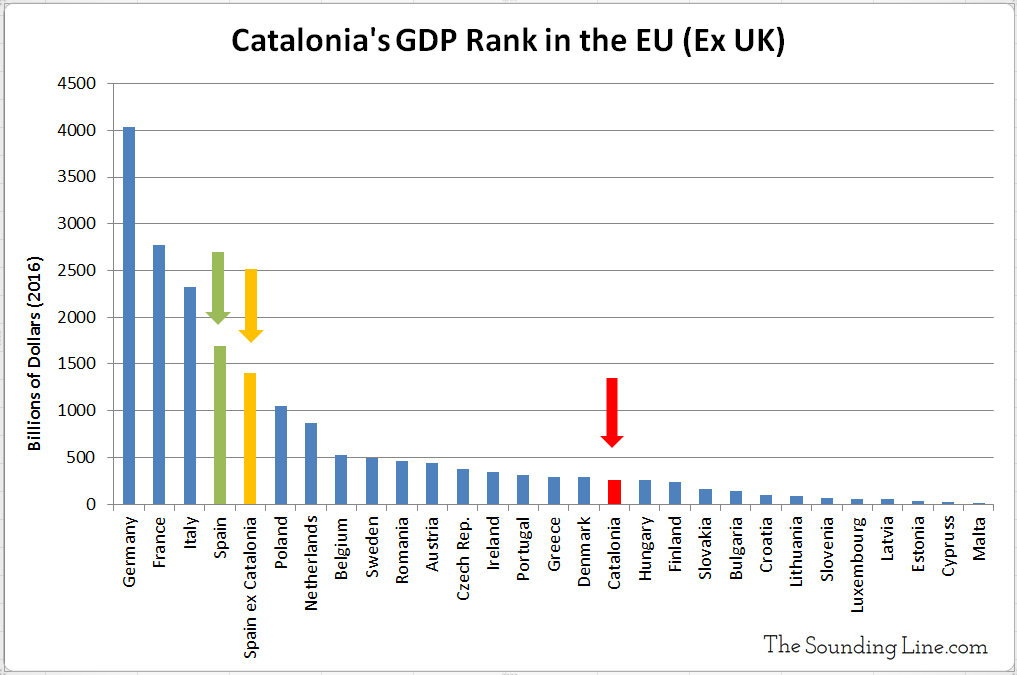

The GDP of Catalonia is roughly $266 billion. While small, Catalonia’s economy is larger than 12 other countries in the EU including: Hungary, Finland, and the Baltic countries combined (Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania). On the other hand, Spain’s economy would shrink by about 20% without Catalonia.

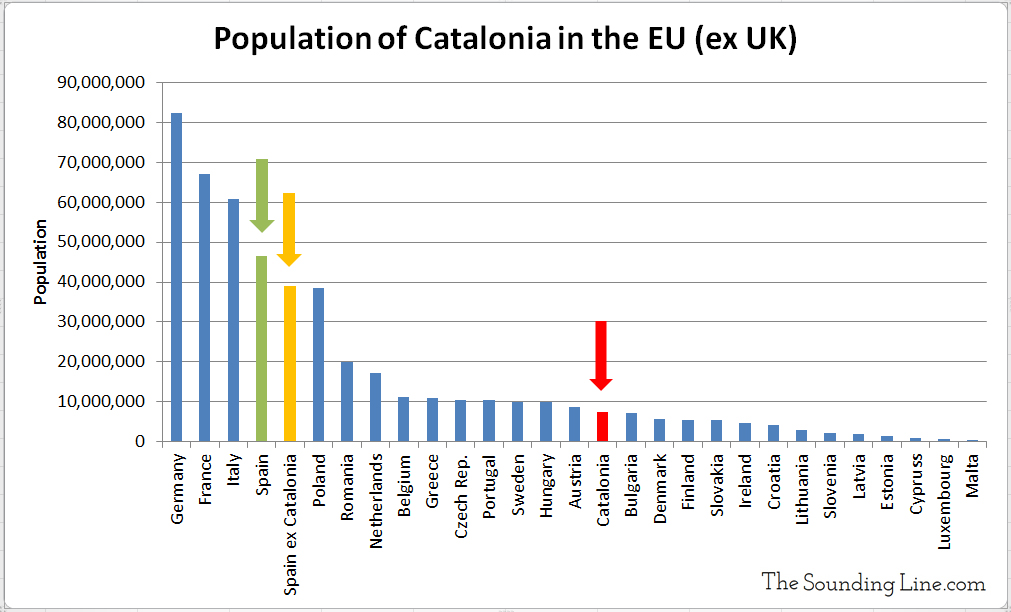

The population of Catalonia is just over 7.5 million people, making it more populous than 13 EU countries. Spain’s population, without Catalonia, would fall from 46.4 million people to just under 39 million, bringing it closer in size to Poland’s population.

Catalonia’s unemployment rate is quite high at 15.3%, twice the EU average, yet it is less than Spain’s overall rate of 17.6%. Due to the economic disruptions that a separation would cause, both countries would likely see steep rises in unemployment in the event of Catalonian independence.

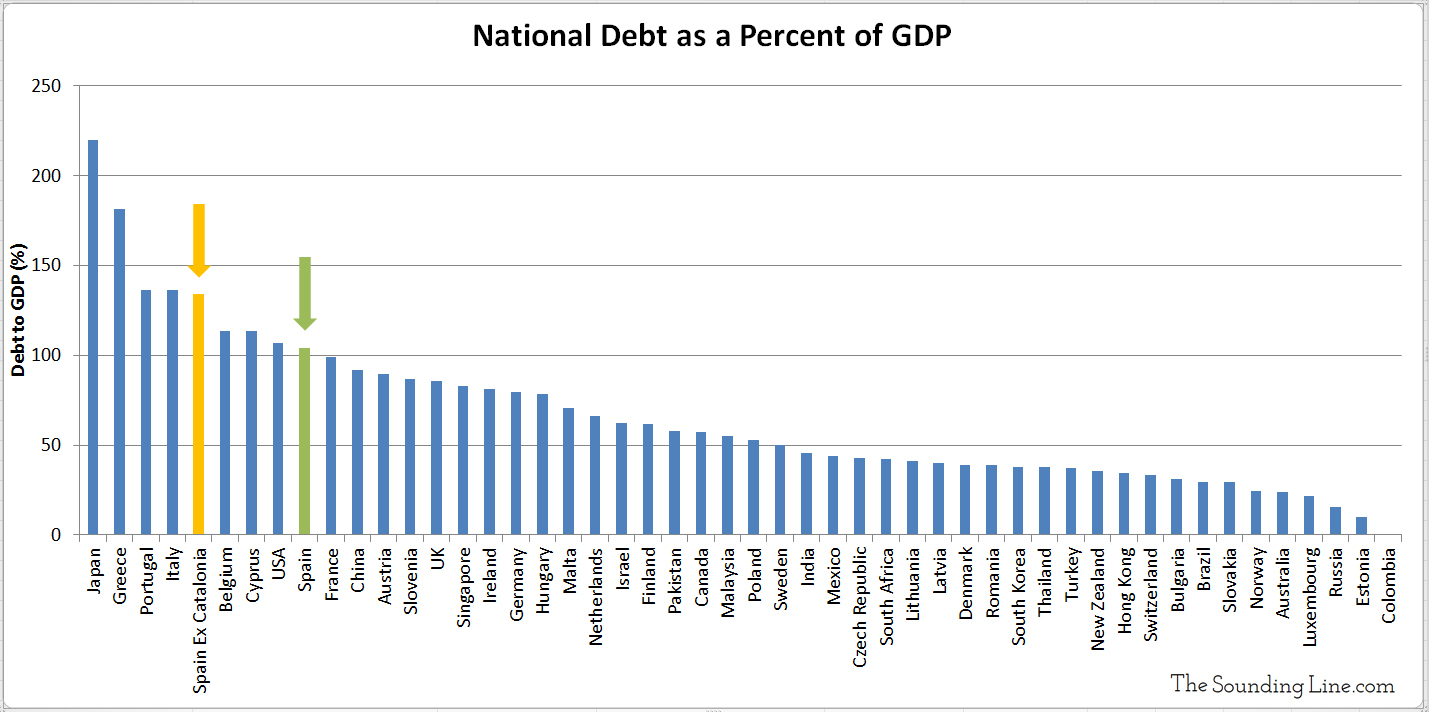

Importantly, Catalonia is responsible for about 20% of Spanish tax revenues despite accounting for only 16% of its population. If Catalonia were to split from Spain, Spain would maintain the same amount of national debt but it would have a smaller economy and fewer taxpayers to support that debt. Accordingly, Spanish government debt-to-GDP would immediately jump from 104% to 134%. At 134% debt-to-GDP, Spain would leapfrog Belgium, Cyprus, and the US to become the fifth most indebted government in the world relative to its economy.

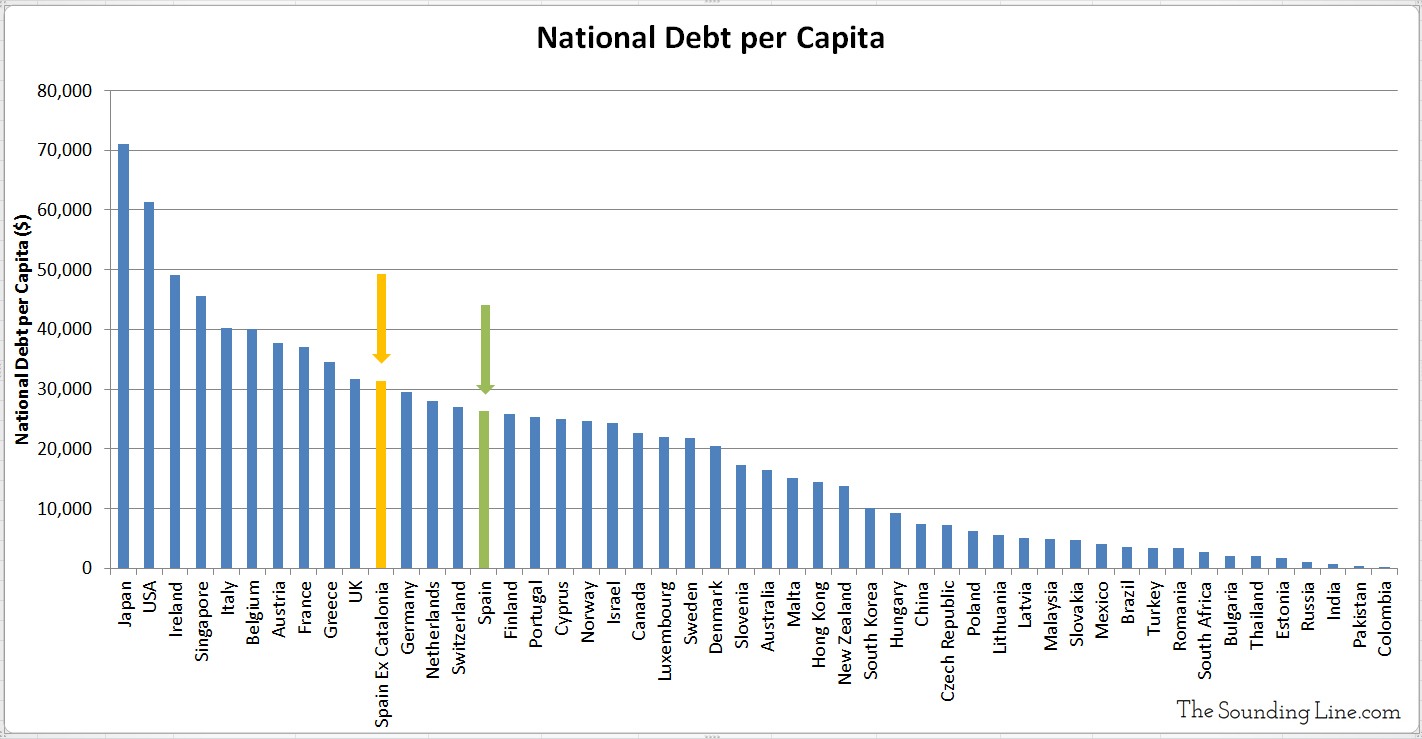

After losing 7.5 million residents, Spain’s government debt per capita would jump from about $26,000 per person to over $31,000, leapfrogging Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland.

It is safe to assume that Catalonian independence from Spain would dramatically degrade business and investor confidence in both Spain and Catalonia, resulting in serious and lasting disruptions to both economies. With a current government debt-to-GDP ratio over 104%, Spain already struggles with the over-indebtedness of its central government and economy. The loss of the Catalonian economic and tax base, the messy legal and economic consequences of a separation, and investor uncertainty over Spain’s ability to service its debts could throw Spain, and potentially other EU countries back into the thick of the highly destructive sovereign debt crisis from which they have just barely emerged.

It is because the stakes are high for Spain that their approach up to this point has been so perplexing. Instead of meeting Catalonia half way on earlier demands for greater autonomy within Spain, the Spanish government has consistently opposed Catalonian demands. As Wolfstreet recently noted:

“The most recent tensions were inflamed in 2010, when Spain’s highly politicized Supreme Court, at the urging of the now governing People’s Party, annulled many of the articles of Catalonia’s recently agreed Statue of Autonomy, effectively stripping the agreement of any meaning. Gone was any chance of any fiscal autonomy. That this happened just as the Financial Crisis was beginning to bite in Catalonia hardly helped matters.”

“Since then, the Rajoy administration has refused to offer greater fiscal autonomy for Catalonia, or the chance to hold a legitimate referendum on national independence. The argument is always the same: the 1978 constitution forbids it from doing so and it can’t change the constitution, although the Rajoy’s party voted to change the constitution to enable Spain’s bailout of its savings banks while in opposition in 2011.”

“Catalonia’s regional government, the Generalitat, in the face of such intransigence and seeking to deflect public attention from the brutal austerity cuts it was making, began to take matters into its own hands. Little by little, disobedience became defiance, which gradually evolved into open rebellion.”

Most of all, the police crackdown on the referendum appears to have succeeded only in enraging the Catalonians and driving them further from the Spanish government. The one thing that the police action failed to do was actually prevent the referendum from taking place. By all accounts, voters participated in the referendum and the overwhelming majority supported independence. It is difficult to conceive of a worse outcome for Spain. To make matters worse, so far there has been no attempt at reconciliation by the Spanish government since the referendum. The Spanish government, either through intent or incompetence, is forcing a showdown with a soon to be self-declared independent Catalonia government and it’s hard to imagine that ending well for anyone.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

What on earth makes you think that if a new country secedes from an old one, the old one keeps the entirety of the debt and the new country comes out clean? That would be equivalent to a massive theft, one that no country in the whole world would allow, even if a secession were to be permitted (which, again, no country in the world will allow if it’s done ilegally). And it’s funny to believe that Spain would suffer more than Cataluña in case of secession, when Spain would remain in the UE, when Spain remains the larger economy… Read more »

The Spanish central government debt exists in the form of bonds issued by the government of Spain. There is no mechanism or precedent for the government of Spain to hand responsibility for repaying those bonds (or any portion of them) to any third party. That would constitute a default by Spain. I could go on about things like how would Spain determine what portion Catalonia is responsible for and what if Catalonia rejects that, or the issue of how Catalonia could be expected to accept legal responsibility for those bonds and pay if it isn’t a legal state, or the… Read more »