Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 6th of December 2019 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe.

The following example highlights why official CPI numbers can be misleading when determining changes in the actual cost of living, particularly for lower income individuals:

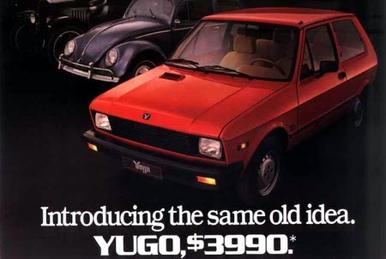

In 1990, the cheapest new car in America was a Yugo GV, with a manufacturer’s suggested retail price of $3,990. Although the Eastern-European ‘Yugo’ brand is no longer in existence, over 141,000 units were sold in the US between 1987 to 1992. While the Yugo was exceptionally cheap, other cheap cars of the time weren’t profoundly more expensive. The Hyundai Excel cost just $4,995 and the Dodge Omni started at $5,799.

In 2019, the cheapest car in America is a Chevy Spark, with a manufacturer’s suggested retail price of $15,159.

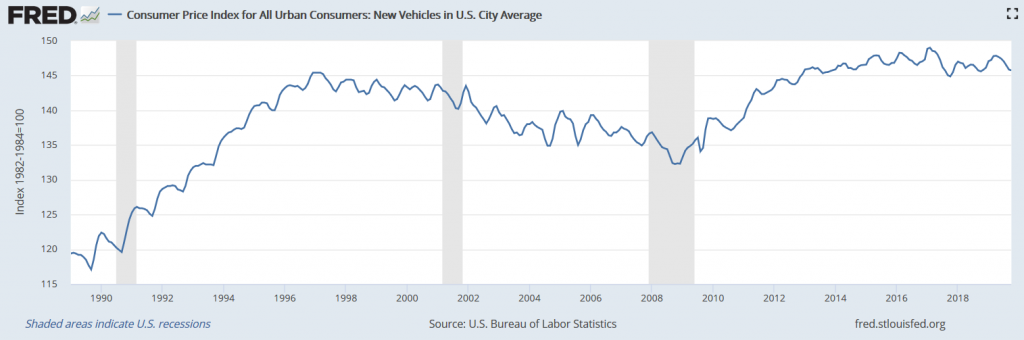

The price of the most affordable new car in the US has risen about 380% since 1990. Put in terms of income, the cheapest car in America represented about 28% of the median person’s income in 1990. Today, it represents 45%. Meanwhile, the official CPI inflation measure for new cars suggests that there has only been 17% price inflation since 1990.

There are a number of reasons for the discrepancy between the CPI inflation number and the actual increase in the price of a cheap new car in the US. To begin with, CPI measures changes in the price of the average car, not the cheapest car. The price rise between an average car like a Toyota Camry in 1990 and today, is closer to 80%, still much more than 17%, but less than 380%.

The rest of the difference comes through “Hedonic Quality Adjustments.” When the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics calculates inflation, they eliminate any price increase attributable to an increase in the quality or performance of an item, or changes in the composition of that item. The argument goes that if the price of a car goes up because it gets better, safer, or faster, or has somehow changed in composition, then it is not inflation that is causing that price increase. It’s changes in the product itself. While that may make reasonable sense when trying to determine an inflation rate, it is besides the point when trying to measure the increase in the cost of living for someone who can only afford the cheapest options, particularly if ‘unimproved’ products no longer exist. In the case of very cheap cars like the Yugo, they cannot be produced economically within today’s regulatory environment and modern equivalents simply aren’t sold in the US. In the case of the Yugo, the car ceased to be imported after failing to pass emissions tests in 1992.

Since 1990, safety regulations on cars sold in the US have been expanded to include LATCH child safety seat systems, electronic stability control, and front airbags. Fuel economy standards have also been kicking in since the 1970s, mandating all sorts of changes to materials and engines. An incalculable list of regulations have been added to the various sub-components that wind up in cars. Many of those regulation are not automotive in nature, but they still effect the parts, materials, and design of cars. In most cases, the BLS removes their costs from the CPI number.

Undoubtedly, the quality and features of a Chevy Spark are much better than that of a Yugo. Indeed, the features of any car today are likely superior to a car from 1990. However, you can only enjoy the qualities in a car if you can actually afford to buy it. For a person simply looking for the cheapest new car on the market, regardless of how good that car is, it has gone from costing them about a quarter of their annual income (assuming median income), to nearly half of it.

The same story has played out with many common expenses. The rise in the price-per-unit-of-quality may be roughly reflected in CPI numbers, but the fact that low end choices no longer exist is not.

Updated: The first version of this article was not precise with regards to the point that I was poorly attempting to make, so I have rewritten most of it. My apologies.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

“Put in terms of income, the cheapest car in America represented about 28% of the median person’s income in 1990. It represents 45% in 2019.”

That seems to be the key there, it’s risen by 61% of the proportion of income over the years, not 17% as CPI might suggest.

When they are advertising insurance policies to get your car fixed, you know something is wrong with this picture.

The CPI automotive component is for all cars, not just the cheapest one, weighted by what share of the market they held for new cars. Hugo’s were just not a very big part of the new car market. I think you are cherry-picking for something sensational to say.

Indeed, CPI automotive is not for the cheapest car, it is for the average car. Yugo’s are not a big part of the automarket, but other cheap cars were roughly similarly priced, as the article notes.

The point of the article is that using CPI inflation to judge changes in the cost of living is misleading, particular for someone at the entry level.

Also, this is not my best article…