Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 30th of August 2018 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

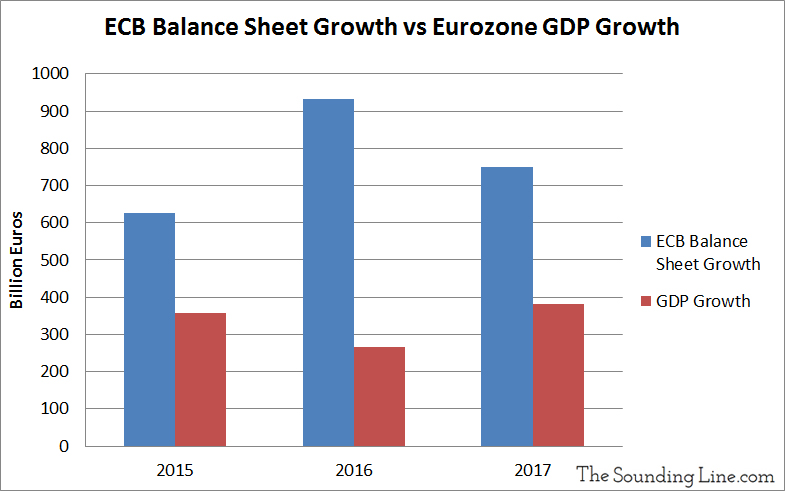

The long-heralded end to the European Central Bank’s (ECB) quantitative easing (QE) program is fast arriving. The ECB continues to maintain that it will stop expanding its balance sheet by the end of 2018. Doing so would mark a turning point in nearly a decade of money printing which has reached a stunning level, equivalent to 40% of the Eurozone’s GDP. The ECB’s QE campaign has reached such proportions that it has grown by more than the Eurozone’s GDP for three years running. As the following chart shows, the ECB’s balance sheet grew by several times more than the Eurozone economy in 2015, 2016, and 2017.

The ECB’s balance sheet is on pace to outgrow the Eurozone economy this year as well, despite the ECB’s plan to end the program this winter. The ECB is insisting that the Eurozone economy is finally strong enough and inflation high enough, that it can reduce its monetary accommodation and end its QE program. While inflation is accelerating, economic growth is markedly slower than last year. Eurozone GDP in the first two quarters of 2018 has been 0.4%, essentially half the rate seen in 2017. The Eurozone’s inflation rate is not primarily rising due to healthy factors like accelerating economic growth, strengthening consumer confidence (which is the most negative it’s been in years), or accelerating wage growth (which remains stagnant and below the inflation rate). Inflation is rising as a result of a depreciating currency, declining foreign direct investment, negative interest rates, and excessive money printing at a time when the US monetary base is contracting.

The ECB is not ending QE because it is confident in a strengthening economy but because it is concerned about the prospect for inflation (currently at 2.1%) continuing to rise further above its 2% target. To make matters worse, for years the ECB has been printing money and buying government debt faster than all the governments in the Eurozone have been borrowing, in essence financing 100% of budget deficits in countries such as Italy. If not the ECB, who will lend to the Italian government at very low interest rates amid rising inflation, growing deficits, and increased currency risk while its economic growth remains below 1%? It’s hard to imagine who because no one other than the ECB has been a net buyer of Italian government debt for years.

The unfortunate consequence of years of overly accommodative monetary policy form the ECB is that it has achieved its long-wished-for goal of 2% inflation for all the wrong reasons.

P.S. If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Your article highlights several issues concerning the Euro-zone and raises a few questions. The first and most important is just how much of the growth in the GDP was actually based on good solid quality economic production. If the so-called growth was the result of adding and caring for a huge number of immigrants that would be a big red flag. Another has to deal with just what the ECB bought and where the money went as they expanded their balance sheet. As your article pointed out a lot of it was spent on buying bonds from debt-ridden countries at… Read more »