Submitted by Taps Coogan to The Sounding Line on the 31st of January 2016

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

In this post we will look at the intersection of three ideas.

- First there has been a clear divergence between Germany and other members of the Eurozone (Part I here).

- Second the E.U. countries that first adopted the Euro have experienced slower growth and deteriorating employment compared with the European countries that have maintained their own currencies (Part II here).

- Third, as recent history can attest, relatively small countries like Greece are persistently threatening the stability of the Eurozone and sending global markets into turmoil.

This leads us to ask the following question:

“Why has the adoption of the Euro benefited a few countries to a greater extent than or even at the expense of others, and why do small countries like Greece create such large systemic risk for the Eurozone and global markets? “

Countries that utilize the Euro currency are suffering from the flawed structure of the common currency system that transfers a disproportionate amount of economic productivity to Germany and increasingly destructive debt to other member nations.

The flaw is the combination of three critical elements of the Eurozone system that, when taken together, create an unsustainable system. These three elements are:

- A single currency union that prevents member nations from having individual national monetary

- While at the same time allows for member nations to implement independent fiscal, regulatory, and labor policies

- But that lacks a single and critical instrument found in other “federal” systems: a consolidated Eurozone debt instrument that is independent of any one member country (analogous to Treasuries in the U.S.)

The tension between these elements results in capital gravitating to the strongest, most competitive, and ‘free market oriented’ economy. That most competitive nation is Germany (see here). Weaker member countries cannot respond to this movement of capital because their ability to create independent national monetary or trade policy has been eliminated. As such, the normal balancing forces of creative and reactive policies at the independent national level are eliminated. This leads to the accelerated economic divergence that we can plainly see today.

As certain Eurozone economies deteriorate, it further illustrates that a critical monetary and fiscal policy tool is missing in the Eurozone and at the European Central Bank (ECB). The ECB does not have a single “super national” debt instrument, similar in construction to U.S. Treasuries, and this increases risk exponentially. As frequently noted and advocated by Martin Armstrong (example here), the continued utilization of individual Eurozone nation’s sovereign debt in place of such a ‘super national’ instrument cannot properly reflect, within the interest rate applied, the risks associated with each individual Eurozone nation’s sovereign debt. If risks are not properly priced and rates are artificially suppressed, debts will continue to build within nations until they become a systemic risk to the entire Eurozone. In the long run, suppressing rates does not lower the default risk for any single member country, instead it delays the risk and allows more debt to accumulate. This makes default more likely and of greater systemic risk to the Eurozone and global markets. They key to understanding this is understanding the link between inflation, risk, rates on sovereign debt, and the economic policy of member nations.

- Rates on debt instruments are largely a function of inflation expectations and the risks of default. Higher inflation expectations and higher default risks both increase applied rates.

- To take the example of Greece, by sharing a common currency, inflation that might arise from a weakening economic or fiscal outlook is counterbalanced by strong performance in Germany. If runaway inflation were to somehow happen in Greece, investors could simply take their proceeds to Germany where inflation pressures would presumably be of little concern. This mitigates the inflation risk of debt in Greek debt.

- With the inflation risk component of rates largely eliminated, rates on the sovereign debt of weakened Eurozone countries do not rise fully in relation to their economic deterioration. Thus they can amass more debt at lower rates up until the risk of actual default rises.

- If Greece had their own currency, inflation risks would push rates higher far sooner. This serves as a critical feedback loop for political leadership and economic planners by creating a clear tangible point of diminishing return that would force political leadership, either out of good intentions or through sheer mathematical necessity, to curtail spending and seek means to create real sustainable economic growth.

- In the distorted Eurozone process, rates finally start to rise only due to concerns of actual default. By that point the debt has become much larger than it would otherwise be and this creates greater hazard for Greece and the possibility for systemic risk to the Eurozone.

- As the default of any nation’s sovereign debt becomes a systemic risk to other member countries, the European Central Bank (ECB) or other members of the Eurozone are forced to step in and provide exceptional policy or bailouts in order to save themselves from cascading defaults and loss of confidence. This intervention suppresses rates again and the debt builds further beyond the amount that was already a default risk. A desperate loop is created where the risk becomes more systemic and thus the effort to suppress rates becomes greater, allowing more debt to accumulate.

- The final and most critical flaw that truly enables these problems and produces enormous systemic risk is the lack of a ‘super national’ debt instrument analogous to treasuries. Treasuries provide the U.S. banking system and the Fed with an instrument to facilitate interbank reserve lending and allows the Fed to target the ‘Fed Funds Rate’ using instruments that actually have very small yet measurable risk. That greatly diminishes the chances of any one state’s debt (Alabama or New York for example) from permeating the system and creating systemic risk. This frees politicians, private banking members, and the Federal Reserve from the need to backstop state debt to avoid national or international financial crisis (see Puerto Rico here ). In a Treasury based system, state debt more closely reflects real risk. Because the Eurozone doesn’t have such an instrument, it must either use debt provided by all the other member nations, some of which already have real risk, or grant privileged status to certain member countries and exclusively use their debt. These types of special privileged arrangements carry a highly disruptive and corrosive political effect.

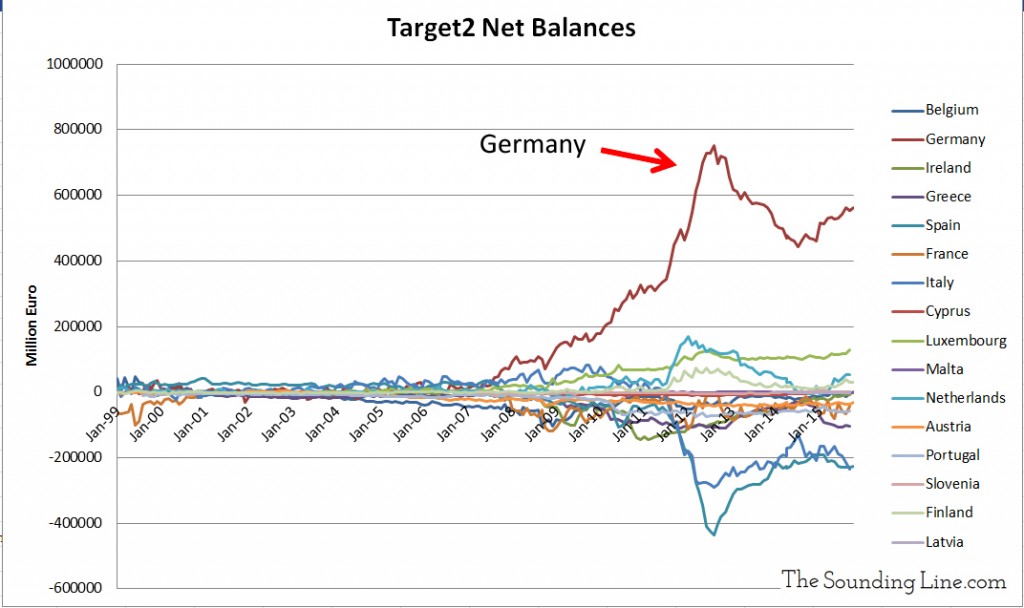

There is a metric that can allow us to visualize one element of this systemic risk. The Target2 balance represents the money ‘owed’ to the ECB by the various national central banks in the Eurozone. A fairly concise explanation of the statistic can be found here (link). Put simply, if someone with a Greek bank account owes money to someone with a German bank account, that debt can be settled through the Target2 system that allows the monitoring of the net balance of payments owed by the various central banks. Positive values indicate that the central bank is owed money and negative values indicate that it owes money. From this metric we can see that one of the risks that German banks would face, if the Greeks started a cascade of defaults and Euro departures, is approaching 600 billion euro.

Data Source and More info (here)

With upcoming votes scheduled in a number of key European nations on the subject of continued participation within the European Union and/or adoption of the Euro, much of the decision by those members will be based on the benefits achieved or lost thus far in this grand experiment. One thing is most certainly clear, only one nation has seen clear benefit so far. With another Eurozone debt crisis looming, for Eurozone members who haven’t strongly benefited from adopting the Euro, why not get out ahead of the problem instead of waiting for the worst time and worst reasons to re-establish national currencies?

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.