Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 26th of March 2016 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

A central argument put forth to oppose a British exit is the idea that membership in the common market of the EU has aided British industry by allowing them to export more, particularly to the EU, than they would otherwise be able to do.

In order to evaluate the veracity of this claim we answer four questions.

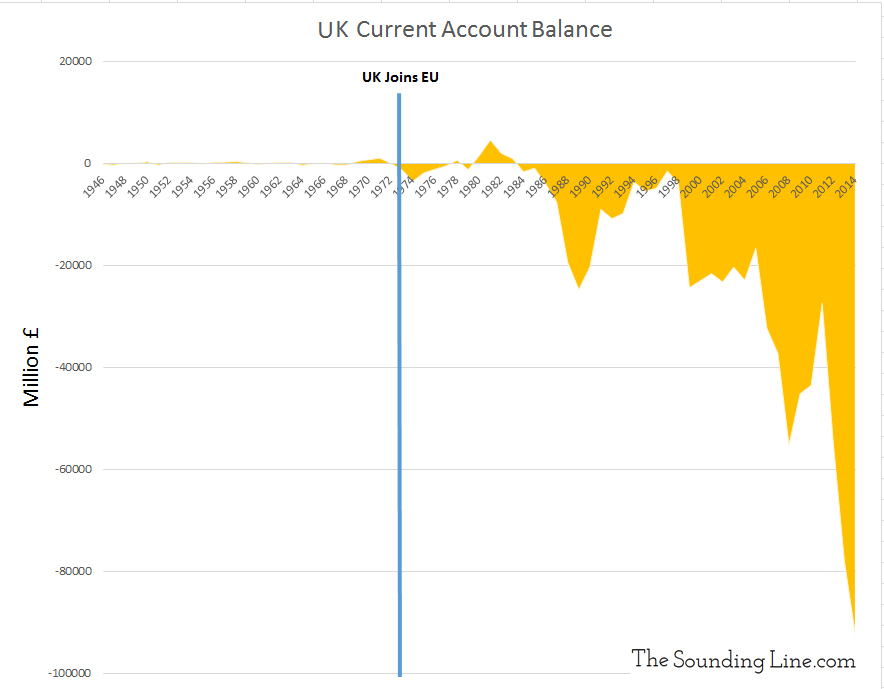

1. How has the UK’s balance of trade changed since joining the EU?

The UK current account balance is the net sum of all transactions between residents of the UK and the rest of the world and is a comprehensive measure of the UK’s balance of trade. Prior to joining the EU in 1973, the UK maintained closely balanced trade regularly posting small trade surpluses. Since 1973, the year they joined the EU, the UK has not maintained a positive current account balance of any consequence. In fact, the last time the UK had a positive account balance was 1982. The deterioration seen below is clear, with the period following the 2006 global downturn creating a balance of trade free-fall for the UK.

It is a similar case for the UK’s trade within the EU community itself, the very thing that was the purpose of membership. The chart below shows that the UK’s balance of trade with the EU has deteriorated since 1996, the earliest date for which data was available. The UK is now a net importer from the EU.

Based on the UK’s negative current account balance and negative trade balance with the EU, the UK’s balance of trade has not experienced a net benefit from EU membership. Quite to the contrary, the reciprocal nature of the UK’s access to the EU marketplace and the associated regulatory restrictions appears to have benefited foreign producers selling their products into the UK at the expense of indigenous British industry.

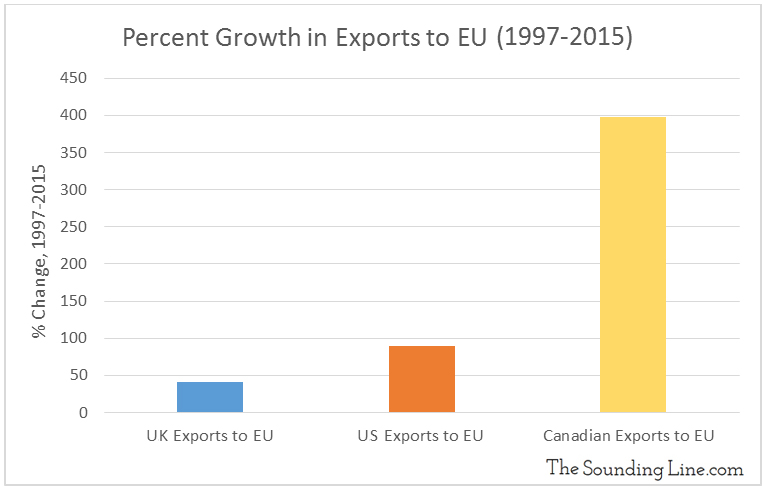

2. How has the growth rate of the UK’s exports to the EU been compared to that of non EU member countries’ exports to the EU?

As the chart below shows, despite not being in the EU and not being members of the supposedly advantageous common European market, both U.S. and Canadian exports to the EU have grown at a far faster rate than the UK’s. This casts serious doubt on the assertion that access to the common market has outweighed the regulatory burden associated with EU membership in helping the UK remain competitive. Instead, it suggests that EU membership is either irrelevant or counterproductive when it comes to exporting to the EU.

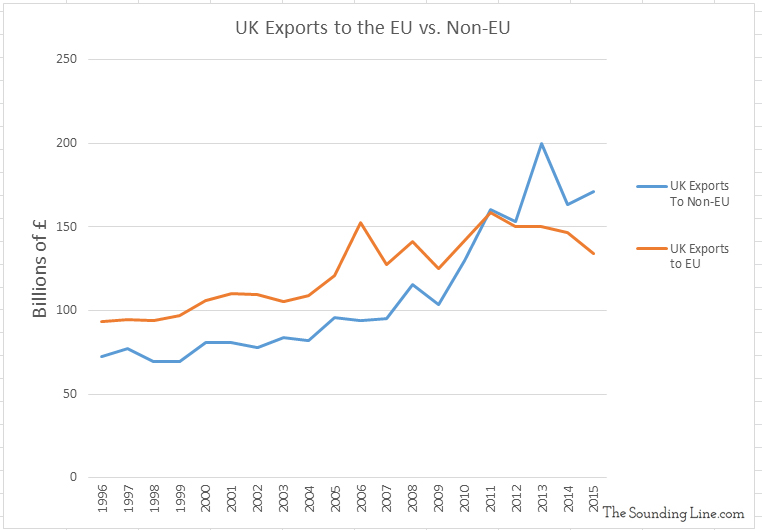

3. How has the growth rate of the UK’s exports to non EU countries compared to exports to the EU?

As the chart below shows, the UK’s exports to the EU have plateaued with exports in 2015 lower than in 2006. Despite this, the UK’s exports outside the EU have continued to grow and have surpassed exports to the EU since 2011. The importance of the EU market to the UK is diminishing while markets outside the EU are growing.

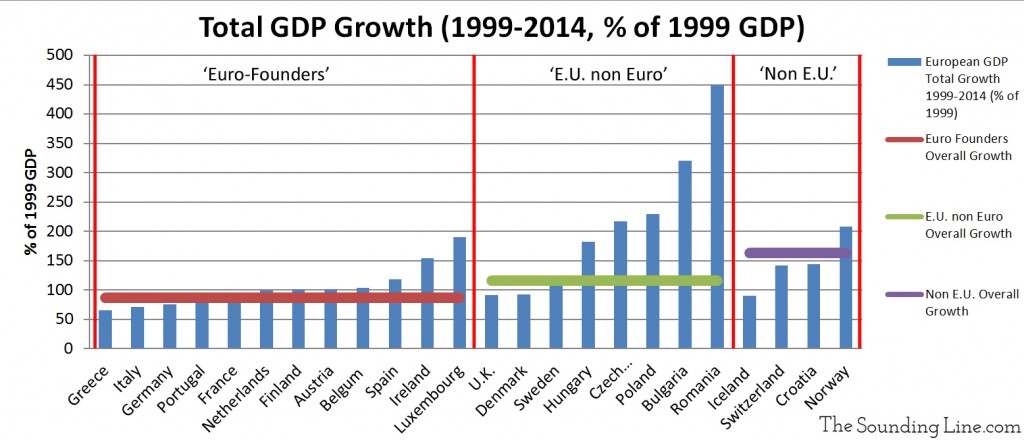

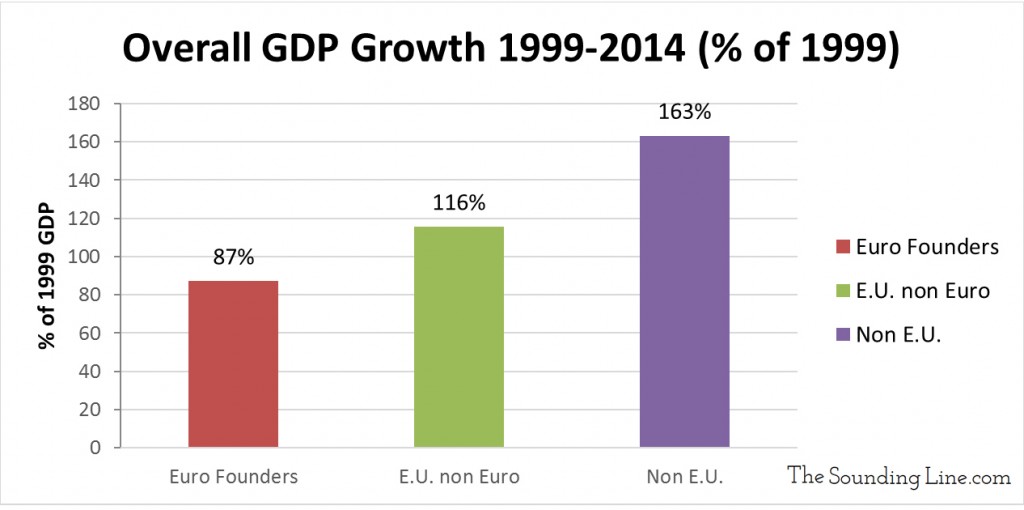

4. How has the overall economic growth rate of EU countries compared to European countries which have opted to remain out of the EU?

As we discussed in ‘Eurozone Help or Hindrance Part II’ (link here), the western European countries which have elected to remain outside the EU (Iceland, Switzerland, Croatia until 2014, and Norway) have experienced significantly faster overall GDP growth than those in the EU. Furthermore, the UK’s GDP growth has been the slowest of all countries in the EU not participating in the Euro currency.

We watch with great interest as the UK makes a critically important choice in the upcoming referendum. To sum up our observations:

- The UK went from balanced trade to massive trade deficits rapidly after joining the EU in 1973.

- The UK became a net importer from the EU and British exports to the EU have grown more slowly than other non EU countries like the US and Canada.

- In fact, the UK’s exports to the EU have not grown at all for a decade and are now smaller than the UK’s exports to the rest of the world.

- The overall economic growth rate of western European countries outside the of EU has been faster than those in the EU, and the UK has experienced uniquely slower growth.

The assertion that indigenous British industry has benefited in regard to global trade, global exports, or trade within the EU via its membership in the EU, is simply not supported by the facts. To the contrary, membership in the EU appears to have exposed British markets to lower cost foreign producers while simultaneously stymieing British competitiveness with foreign regulations.

For those concerned about the risks associated with a Brexit, look not to Britain which has little to lose and much to gain, but to the EU itself. The UK is the second largest economy in the EU. If the EU has geopolitical ambitions, losing the UK would also strip it of the bulk of its military relevancy. The UK invests 50% more in its military than the next largest EU spender, Germany.

Germany and the UK have been the wings keeping the EU aloft. Without the UK, the EU would be left flying with one wing, heavily loaded and aerodynamically unstable. Perhaps the more pressing question is will the Germans want to remain in an EU absent the UK?

P.S. We have added email distribution for The Sounding Line. If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Remove politics from the argument and there is no argument to make for the UK remaining in the EU.

The US and Canada have free trade agreements, relatively easy movement of people across the border, and the largest cross-border trading relationship in the world. All this without a ‘North American Union’ or a political superstructure analogous to the EU. You are correct that the EU is an expressly political project. There are countless counter examples to idea that the political control demanded by the EU is needed to allow for free trade, harmonization, or convenient travel between nations.

It’s far more complicated than that. The UK (and other developed contries) starting going downhill coincidentally at the same time the EU was taking off. Did the US turn into a sh|thole because of Europe too? Or was it due to the slow departure from the common sense values that our grandparents used to have?

Of course it is more complicated then just that. But it is part of a mosaic of problems, some controllable and some not, that have been hampering western economies for decades.

One difference between Norway & Switzerland’s relationship with the EU and that which the UK will have is that the UK won’t have the same access to the single market. So surely one can’t infer that the UK would have the same success in exporting to the EU as Norway and Switzerland.

No but they might have as much success as Canada or the US which would be an improvement, as you can see in the charts.