Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 29th of April 2019 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe.

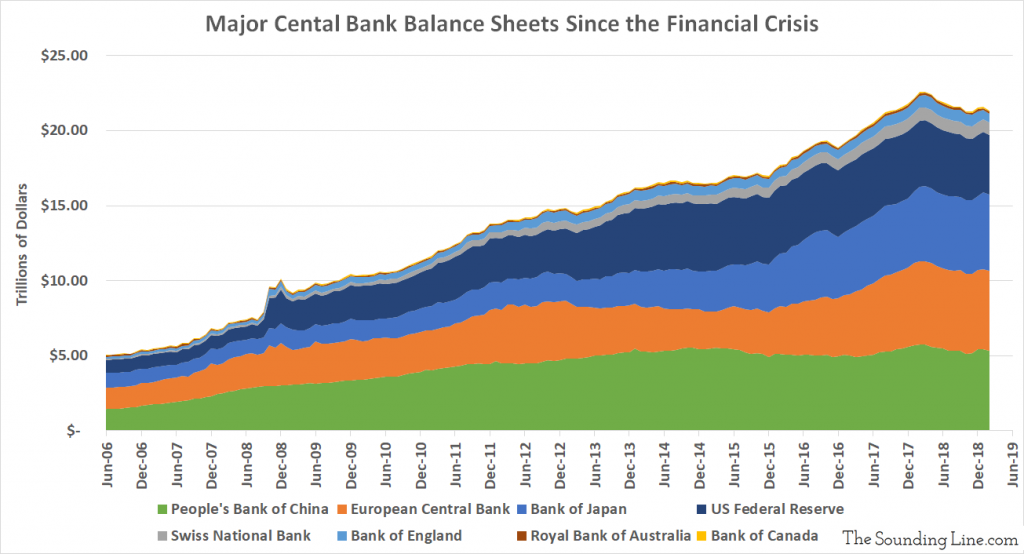

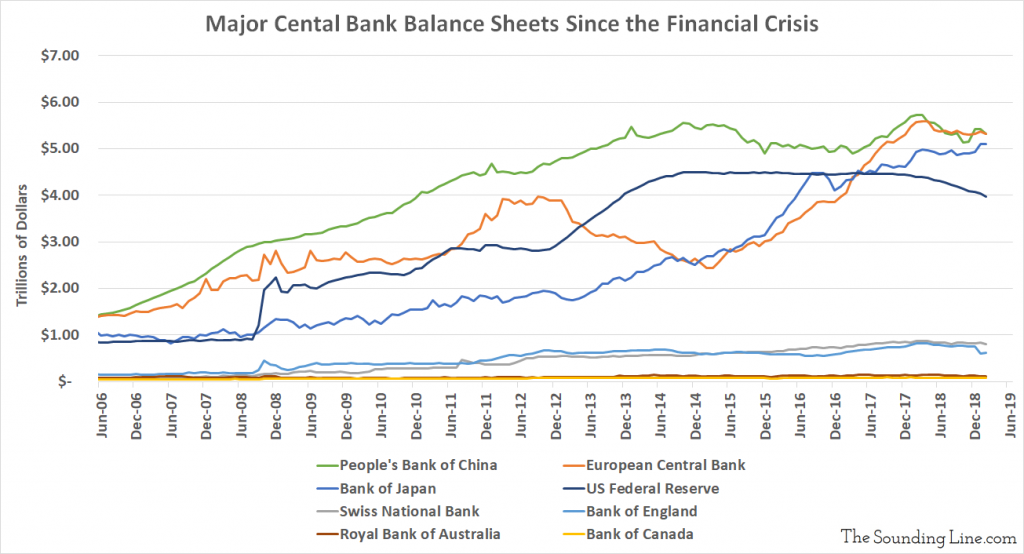

As the following charts show, the deluge of quantitative easing (QE) since the Financial Crisis has driven the world’s central bank asset holdings up from just over $6 trillion in the summer of 2007 to $21.3 trillion as of February 2019, a $15.3 trillion increase. Central banks’ balance sheets are now the size of roughly 20% of all of the non-financial debt in the world.

With the current economic expansion in the US poised to become the longest in American history, and given the recent slowdown in global growth, the question of how central banks will fight the next recession is as important as ever.

With very little room to cut short-term interest rates in any developed economy, QE will inevitably be a central tool used to fight the next recession.

The desired stimulative effects of QE are two fold. QE pushes down long-term interest rates and it displaces investors from low risk sovereign debt markets and into higher risk markets.

Pushing Down Long-Term Interest Rates

Not only are short-term interest rates in all developed countries still very low, so are long-term interest rates. 10-year Treasury yields in the US are under 3%. In Canada, 10-year government bonds are yielding less than 2%. In the UK, they are just over 1%. In Japan, Germany, and Switzerland they are already below zero. Just as there is little room to cut short-term interest rates, there is little room to cut long term interest rates. Pushing deeply into negative territory across the entire yield curve in all developed markets would make profitable banking essentially impossible and would be just as likely to create a financial crisis as it would be to fix one. Central banks can do all of the QE they want, but long term interest rates can only fall a couple of percent in a couple countries before they are likely to become counter productive.

Displacing Investors from Low Risk Markets

Every asset that central banks buy via QE is one that would otherwise have been owned by the private sector. As such, performing QE displaces investors, dollar-for-dollar, into higher risk asset classes or cash. That drives interest rates down and financial asset prices up across the entire spectrum of asset classes.

Unfortunately, central banks have already displaced most of the investors that can be displaced in several key markets. The European Central bank already owns over 50% of the total Eurozone sovereign debt market, the Bank of Japan owns roughly 45% of their sovereign debt market, and the Bank of England owns just under 30% of theirs. Many of the investors that remain in these markets are institutions such as pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, banks, and insurance funds that are legally obligated to hold allocations of sovereign debt. They cannot be displaced.

Once all of the investors that can be displaced from a market have been, further monetization of that market stops being stimulative.

In order to perform a large amount of additional QE, central banks would therefore have to expand to purchasing other assets such as corporate bonds and stocks, as some have already done. However, the entire corporate bond market is worth roughly $12 trillion, less than the amount of QE already performed by major central banks since the Financial Crisis ($15.5 trillion). In other words, central banks could buy every corporate bond in the world and it would represent less QE than they have already done. In the process, they would end all private investment in corporate bonds.

The Bank of Japan and the Swiss National Bank have already started purchasing stocks. The Bank of Japan is already a top 10 share holder in 40% of Japan’s listed companies and the Swiss National Bank owns more Facebook Class A shares than Mark Zuckerberg. When central banks start buying stocks, one has to ask: what exactly is it doing to help the economy? What will be left of the private sector? How could such a policy ever be unwound?

Despite all this, Central banks will almost certainly do QE during the next recession, and probably before. In principal, central banks could do more QE than they did last time, but doing so would require monetizing nearly all of the global sovereign and corporate bond markets. Meanwhile, the point of diminishing returns on QE has probably already been reached. In truth, accomodative monetary policy itself is unlikely to be of much help in the next recession. It may very well be the cause of it.

If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

The most serious problem that is happening NOW is the number of baby boomers taking retirement.Many have planned their lives to afford a comfortable retirement.If they manage to scrape and save to give themselves an income of @ $60,000 pa getting a interest rate of say 3% then most would be just getting by.An average cost today for 2 people retired is @ $52,000 pa(No debts just living costs)then any reduction of interest rates would push millions into poverty.Then what?They become a burden on social services with all the costs involved.They have worked all their lives to avoid the very… Read more »

Indeed. Retirees and savers have been sacrificed at the alter of monetary policies that have done little more than inflate financial asset prices for the rich. The solutions to our economic problems are economic reforms, not tinkering with interest rates.

retirement