Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 29th August 2019 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe.

At the moment, the longest duration bond issued by the US Treasury is the 30-year bond. With a 30-year bond, US taxpayers pay interest on the principal of the bond every year for 30 years and then repay the principal. 30-year treasuries currently yield 1.94% per year, the lowest rate in the history of the 30-year bond. For the last ten years, 30-year rates have averaged closer to 3%. Nonetheless, at 1.94%, by the time the time a 30-year bond matures, its interest expense will by roughly 58% of the principal.

For the first time ever, the US Treasury is now ‘very seriously considering‘ issuing 50 and 100-year treasury bonds. With a 100 year bond, US taxpayers would pay interest every year for 100 years, and then our great grandchildren will pay off the principal.

In an era of massive deficit spending, there are some advantages to ultra-long dated bonds. While only a portion of future deficits would be funded through these new ultra-long bonds, they would allow the Treasury to extend the average duration of the bonds that represent the US national debt. Because the federal government is unlikely to run a budget surplus for the foreseeable future, extending the duration of the national debt means that the government can roll over its debts less frequently. It would also allow the government to ‘lock-in’ today’s historically low rates for even longer. Furthermore, by the time 100-year bonds mature, inflation will have destroyed most of the value of the dollar and repaying the principal will be much easier. During the past 100 years, the value of the dollar has declined by about 95%.

All-in-all, extending the duration of treasury bonds probably makes sense today given that rates are at historic and unsustainable lows.

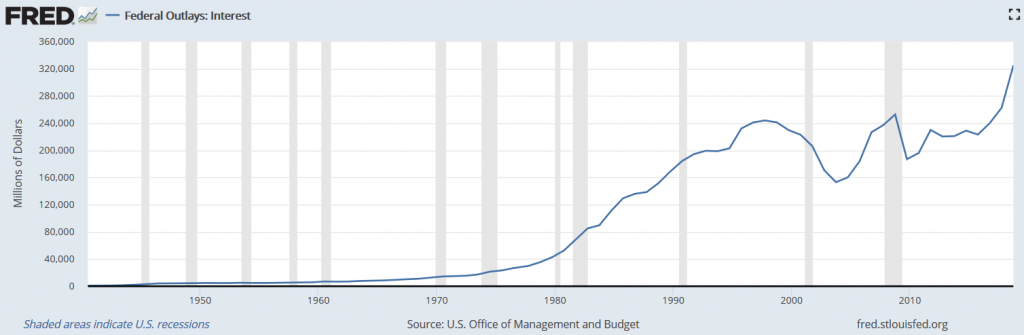

There are, of course, a couple of problems with 50 and 100-year bonds. First, these bonds will likely command higher interest rates than current bonds. That will raise the interest expense on the national debt above current forecasts. The interest expense, $394 billion in 2019, is already the fastest growing federal spending item and is larger than a dozen of major government programs combined. The interest expense is expected to surpass the military budget within the next ten years.

The Interest Expense on the National Debt Is Surging

The second problem with ultra-long bonds is a philosophical one. By issuing 50 or 100 year bonds to pay for today’s decadence, we are obliging our children, grandchildren, and even great grandchildren to carry the burden of repaying today’s ill-advised debts. While inflation will ‘lighten’ the burden of those debts over time, the interest expense on a 100-year bond yielding 3% would be 300% of the principal over its life. If one reasonably assumes a 3% yield and 2% annual inflation for the next 100 years, the ‘real’ interest expense on a 100-year bond will be about 130% of the principal in appropriately sequenced inflation adjusted dollars. Then the principal will have to be repaid, though it will be worth only 13% of what it was when the bond was issued. In other words, extending the duration of our debts does not actually eliminate them, even when accounting for inflation.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.