Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 26th of September 2019 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe.

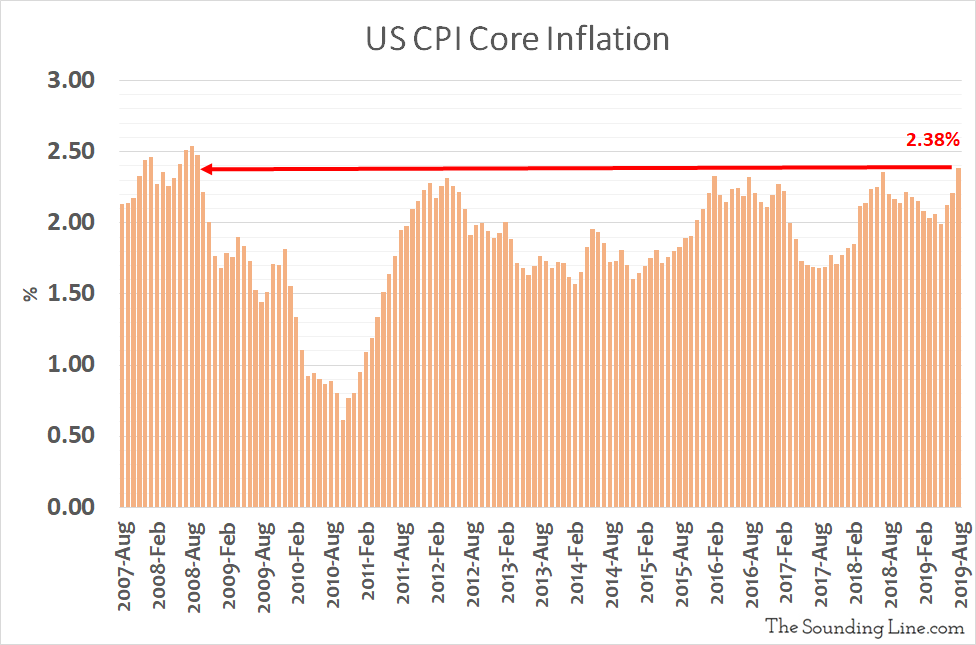

With the Fed actively cutting interest rates and bemoaning a general ‘lack of inflation,’ it might come as a surprise to learn that US core CPI inflation is currently running at its highest rate in 11 years.

For the month of August, the most recent date for which data is available, core CPI inflation rose to 2.38% on a year-over-year basis. It is the highest rate since the Global Financial Crisis.

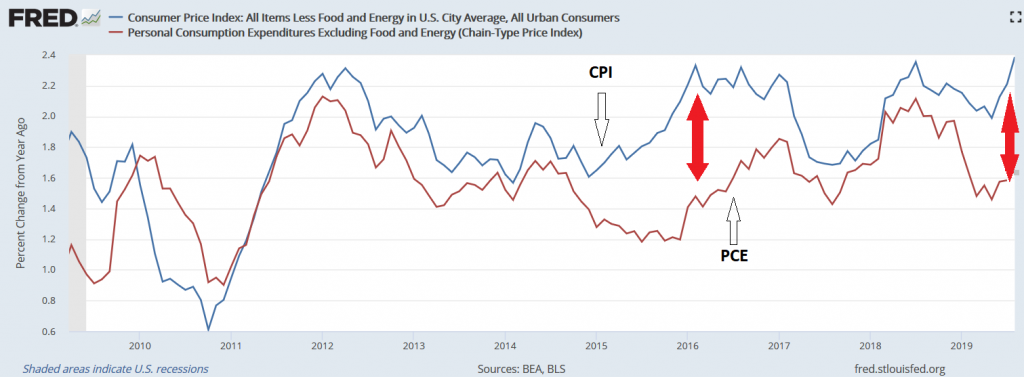

Although core CPI is the most commonly referenced inflation measure, the Fed prefers to use PCE core inflation when setting monetary policy and has a 2% target. For a discussion of the differences between between the two measures of inflation, read here.

PCE core inflation was 1.58% for the month of July, the most recent date for which data is available. While 1.58% is below the Fed’s 2% target, July represented the third monthly increase in PCE and also the average rate of PCE inflation since 2009. Because CPI and PCE inflation are closely correlated (increases in one are typically followed by increases in the other), the PCE inflation rate would most likely have converged towards 2% in the coming months, even without the Fed’s recent rate cuts.

CPI and PCE Core Inflation – Year-over-Year

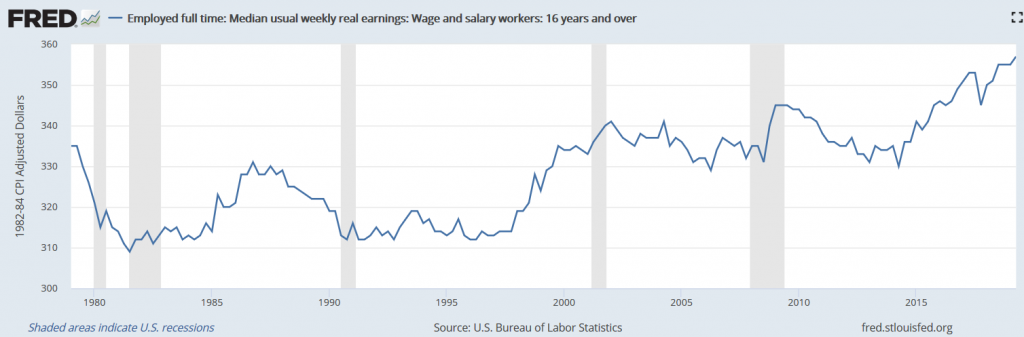

The fact of the matter is that inflation really isn’t very far from the Fed’s 2% target. Considering that unemployment is at a 50 year low and real median wages are rising at their fastest rate since the late 1970s, the recent Fed rate cuts risk embedding a hard-to-get-rid-of inflationary pressure in the economy just as financial markets finish fully pricing in accomodative policy and low interest rates forever (aka negative long term interest rates).

Median Weekly Full Time Earnings

As we have noted before, PCE core inflation was significantly below today’s rate for much of the early 1960s. In fact, PCE core inflation started 1966 at just 1.36%. By the end of 1966, it was over 3% and on its way to 5% by 1971. It peaked at 10% in 1975 and wouldn’t fall below 2% until 1996. In 1996, when inflation fell to roughly where it is today, it represented the culmination of 30 years of painful work to intentionally constrain short term economic growth to combat inflation.

The Fed is supposed to be counter-cyclical, providing stimulus during recessions and removing it during expansions. Cutting interest rates with inflation rising towards 2% and economic growth above average because the economy may weaken in the future is not counter-cyclical, it’s pro-cyclical. It is deploying stimulus during an expansion in the hopes that the expansion continues. It may work for a while, but eventually you end up like the Eurozone and Japan: facing the prospect of a recession with rates already far too low.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.