Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 13th of April 2018 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

The dire financial condition of pension funds across the US has been a frequent topic here at The Sounding Line. At the core of the problem is a simple reality: pension funds have promised to pay out more in retirement benefits than they receive in funding. A new report from the Pew Charitable Trust shines light on the scope and causes of this underfunding problem.

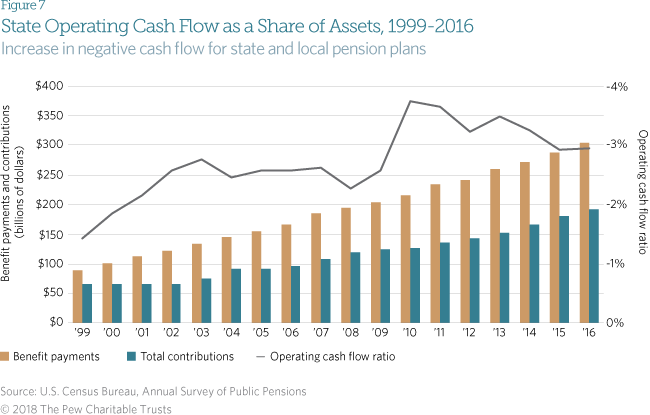

Every year since at least 1999, US state and local pension funds have paid out more in benefits to retirees than they receive in contributions from current workers. The result has been increasingly negative cash flows.

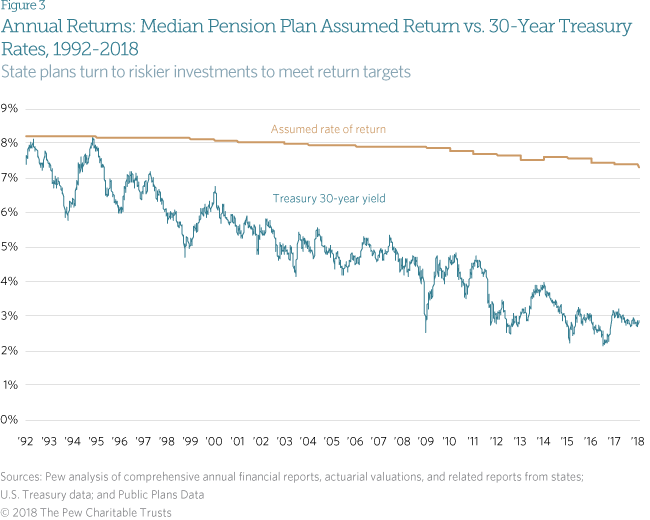

Public pension funds have relied on investment earnings on their assets to make up for the difference between payments and contributions. However, pension funds have been assuming extremely optimistic annualized investment returns. In 2016, the median pension fund expected to earn 7.5% and yet only earned about 1%. The following chart shows the difference between what pension funds are telling themselves that they will earn on their investments and actual ‘risk-free’ returns on 30-year treasuries.

Public pension funds have relied on investment earnings on their assets to make up for the difference between payments and contributions. However, pension funds have been assuming extremely optimistic annualized investment returns. In 2016, the median pension fund expected to earn 7.5% and yet only earned about 1%. The following chart shows the difference between what pension funds are telling themselves that they will earn on their investments and actual ‘risk-free’ returns on 30-year treasuries.

Due to the growing gulf between what pension funds have assumed that they would earn and what they are actually earning in today’s low interest rate environment, pension funds have begun to move into riskier assets in a big way. As Pew notes:

Due to the growing gulf between what pension funds have assumed that they would earn and what they are actually earning in today’s low interest rate environment, pension funds have begun to move into riskier assets in a big way. As Pew notes:

“Twenty years ago, states needed only to exceed the yield on a 30-year Treasury bond by 1 percentage point to meet their investment targets. Currently, the typical state would need to outperform a 30-year Treasury bond by 5.2 percentage points to meet its now-lower investment assumption. That reality has forced plans to take on higher levels of investment risk.”

“The share of public funds’ investments in stocks, private equity, and other risky assets has increased by over 30 percentage points since 1990—to over 70 percent of the portfolio of state pension plans. As a result, pension plan investment performance now closely follows equity returns.”

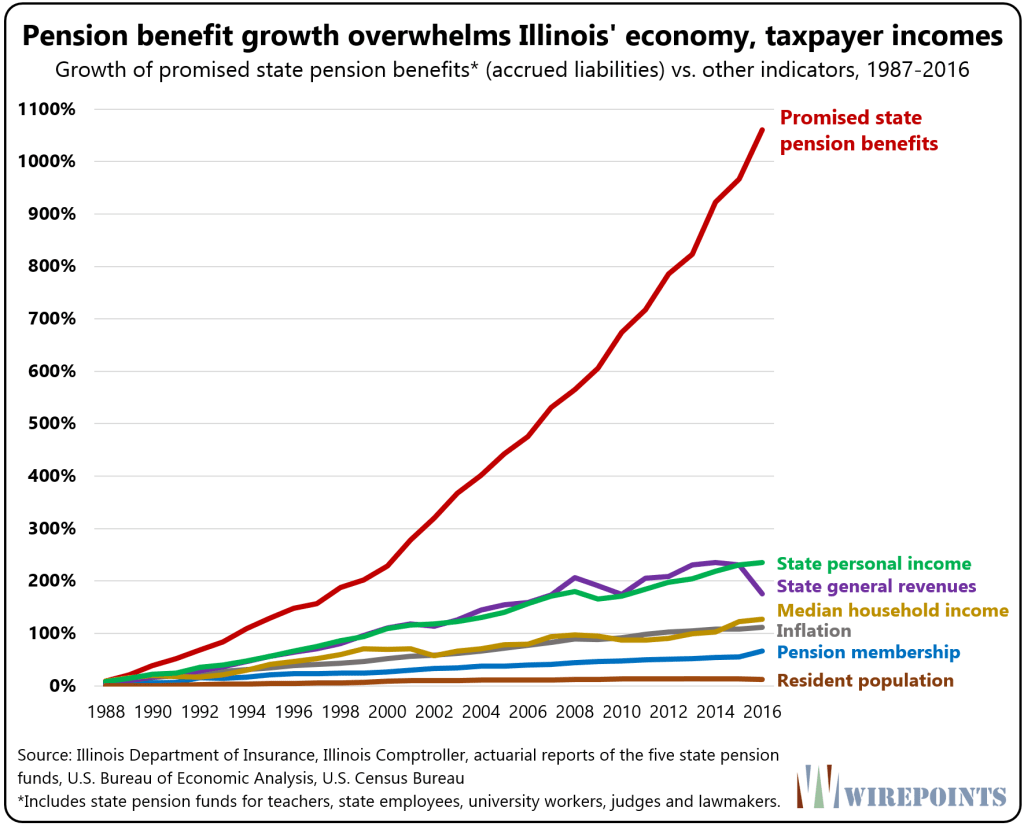

The under funding problem is further compounded by the astronomical growth in promised pension benefits in many states. Promising cushy pension benefits has become an irresistible political currency for unscrupulous elected officials around the country. As we noted here, Illinois, which has one of the most underfunded pension funds in the country, has seen its pension benefits grow six times faster than state revenues and eight times faster than median income.

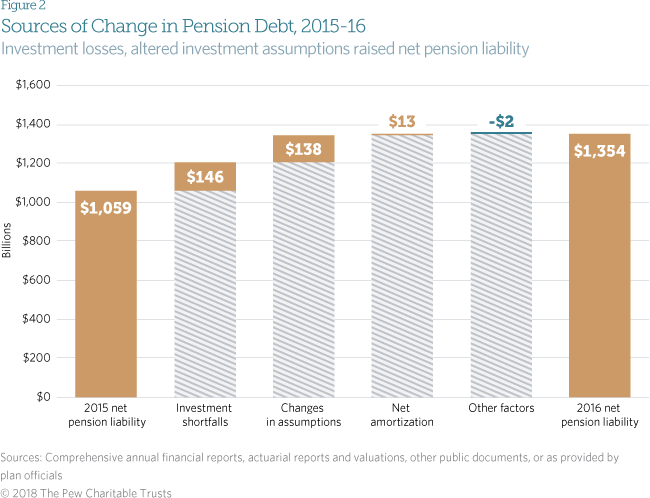

All of this has led to a $295 billion increase in pension underfunding in 2016 alone. As detailed below, $146 billion of that increase was a result of investments under-performing their expectations. The bulk of the rest came from pension funds reducing their expectations for future investment returns, often from 7.5% to a still-impossible-to-achieve 7%.

“Investment returns that fell short of state assumptions caused a major part of the increase in the funding gap. The median public pension plan’s investments returned about 1 percent in 2016, well below the median assumption of 7.5 percent—a disparity that added about $146 billion to the debt.1 Assumption changes—primarily states lowering the assumed rate of return used to calculate pension costs—accounted for another $138 billion in increased liabilities”

“Even if plan assumptions had been met in 2016, the funding gap would have increased by $13 billion because states did not allocate enough to their systems. As a whole, they would have needed to contribute $109 billion to pay for both the cost of new benefits and interest on pension debt; the actual amount contributed, $96 billion, fell short.”

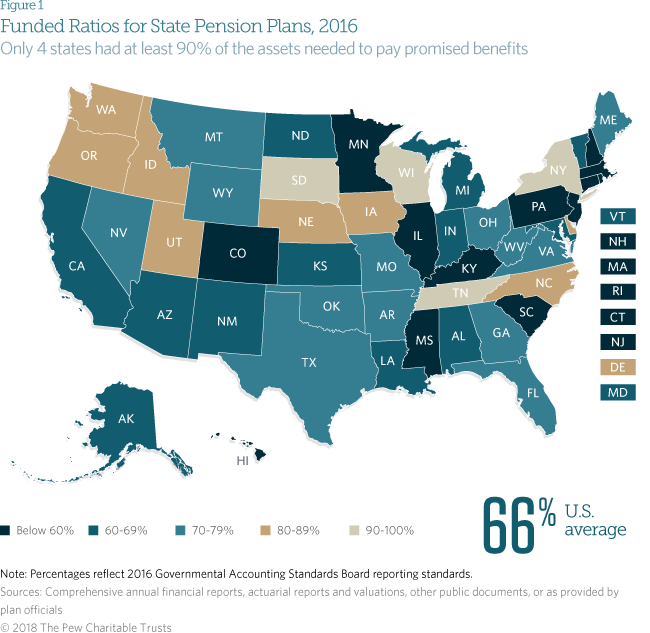

The net result is that the average US state only has 66% of the funds that it needs to pay the benefits that it is committed to pay. Only four states have at least 90% of the required funds: New York, Wisconsin, South Dakota, and Tennessee. 17 states have less than two-thirds of the money required. New Jersey has just 31%.

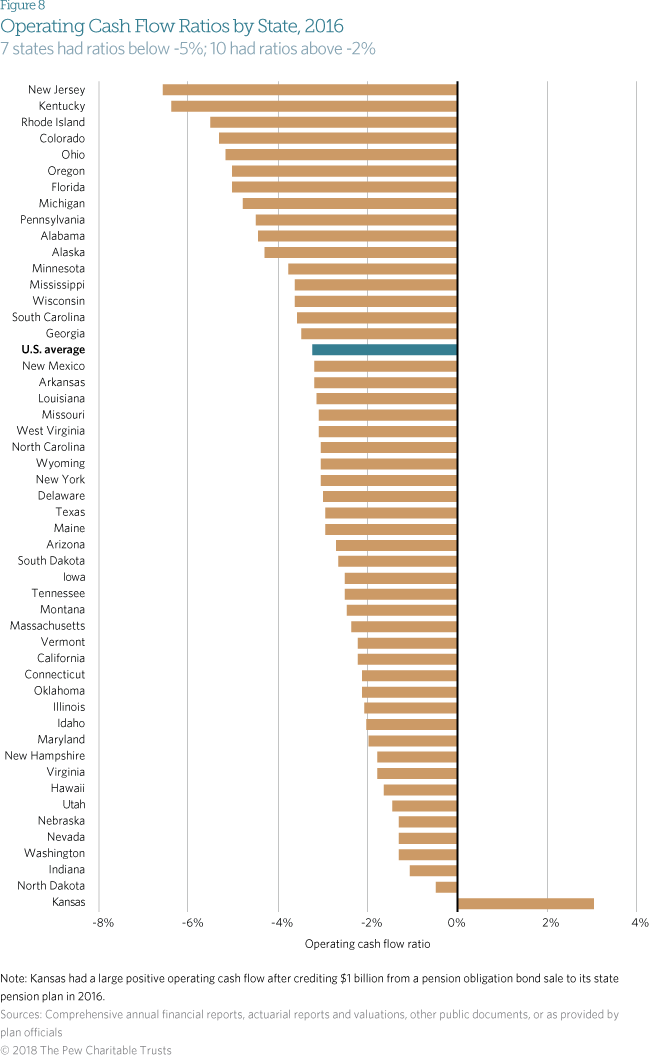

Another way to look at the problem is via operating cash flow ratios.

Another way to look at the problem is via operating cash flow ratios.

“A new indicator, the operating cash flow ratio, represents the difference between financial outflows (primarily benefit payments) and cash coming in before investments (primarily employer and employee contributions) divided by the level of assets at the beginning of the year. A plan with an operating cash flow ratio of 3 percent, for example, would need to achieve investment returns of at least 3 percent that year to keep assets from dropping.”

Accordingly, the chart below shows the cash flow ratios for every state. Only seven states have operating cash flow ratios better than -5%. In other words, many states are likely to see their already underfunded pension funds become much more underfunded. In the end, taxpayers will end up footing the bill for pension plans that private sector workers could only dream of.

Add in the possibility of a recession or decline in the stock market and the future looks dismal for America’s increasingly vulnerable pension system.

Add in the possibility of a recession or decline in the stock market and the future looks dismal for America’s increasingly vulnerable pension system.

P.S. If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

The obvious solution is called ‘face reality’.

Whatever is actually in the pension fund, that is what gets doled out. Period. End of story.

The idea that people with no pensions are on the hook to make good the ‘promises’ to those who resisted realistic payroll deductions to fund the promises made to them is immoral and absurd. What is in your pension fund is what you have. If it is not enough, it is because you defaulted on your fiduciary duty and you can go cry me a river.

That would certainly be one way to fix the problem. Even with entitlement programs like social security

on average SS pays 15K to 25K a year after workers put in 13% of their earning per year far less than public pensions

No reason to cater to high salaried government employees. They who lament a reduction to their overly-generous pensions can join with the ranks of private sector employees thus affected. It is only fair that all Americans share the consequences of bad National economic policies, in fact more than fair considering it was government employees who created such policies.

We hear of pension funds that are soundly invested but then lost to schemes in various ways over time. Loopholes where corporate pension funds are misappropriated need closing and to be stopped cold by laws dedicated to the purpose. Pension funds need a special classification with federal protections and possibly insurance against loss.

Illinois sends approximately $40 billion in net taxes to the Federal Gov’t every.year and is subsidizing other states. If the State rec’d what it paid to the Feds on a net zero basis, the economy and State would be much healthier.

Illinois doesn’t pay net taxes to the Federal Government, the residents of Illinois pay net taxes to the Federal Government, just like many other states and half the US population.

If you include the fact that Illinois’s very high state and local taxes have been deductible from residents’ federal taxes until recently, Illinois has been getting a huge subsidy from states with low taxes where residents actually pay nearly all of their federal taxes to the Federal government instead of to the state.

Illinois is in trouble because it spent too much, borrowed too much, and promised too much.