Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 24th of November 2017 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

The Eurozone is, once again, trying to get a handle on its ‘bad debt’ problem. As the Guardian reports:

“The European Central Bank is attempting to put a lid on the near €1tn (£886bn) of bad debts stored in Eurozone banks by asking lenders to be more prudent about the way they handle new customers falling behind on repayments.

The Frankfurt-based institution issued guidance on Wednesday intended to stop a new pile of problem debts being built up inside Eurozone banks by setting out how much cash it wanted lenders to set aside for bad debts incurred from January 2018.

The measures are not applicable to the existing €1tn of bad debts, which are largely a legacy of Europe’s financial problems in the aftermath of the 2008 crash and languishing on the balance sheets of banks in countries such as Greece, Cyprus and Italy.

The ECB wants lenders to set aside 100% of the value of an unsecured loan within two years and gives lenders seven years to put aside the full amount of a secured loan, such as a mortgage.”

As noted above, this effort will not effect the approximately €1 trillion in bad debt already on the books of Eurozone lenders. Instead, it focuses solely on keeping the problem from getting worse. While this is a start, it begs the question: just how bad is the problem already?

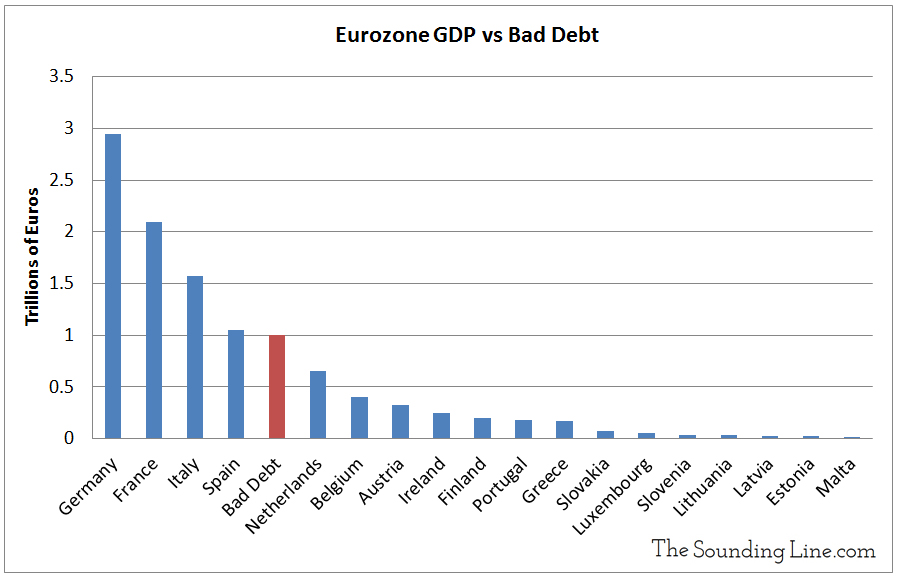

To put approximately €1 trillion of bad debts in perspective, consider this: the gross annual economic output of Spain (Spain’s GDP) is estimated at €1.05 trillion. In other words, the bad debt problem in the Eurozone is the size of its third largest economy and probably growing faster. Here is how the Eurozone’s bad debt problem would stack up if it were a country:

The Eurozone’s bad debts are bigger than the gross annual economic outputs of Ireland, Finland, Portugal, Greece, Slovakia, Luxembourg, Slovenia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Malta combined. Furthermore, these loans are not evenly distributed across the Eurozone. Instead, they are concentrated in the weakest economies: Portugal, Italy, and Greece. As we have discussed on numerous occasions, these countries have seen some of the worst long term economic growth in the world. When accounting for inflation, Greece has seen negative 3% GDP growth since 2000, Italy has seen just 1%, and Portugal has seen just 6%. In fact, this weak growth is a primary reason for the bad debt problem in the first place. As these economies languish, borrowers of all stripes struggle and fail to repay their debts.

The recent uptick in economic growth that the Eurozone has enjoyed so far in 2017 is forestalling the inevitable. When that growth slows, as it eventually will, this bad debt problem is going to put enormous strain on an already fragile financial system.

P.S. We have added email distribution for The Sounding Line. If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Presumably GDP is the GDP figure for one year.

Of course bad debts figure is far higher than it should be, but the GDP figures are one years GDP for each country listed.

Yes these are annual GDPs. The non-performing debt in the Eurozone is bigger than the annual economic output of the various countries listed. That is the point of the article. I added a couple words to make that more explicit. Thanks for the clarification

The equivalent statistic for the US is substantially less than 1% of GDP. At it’s peak in 2010 is was about 2.5%

Thanks Taps.

The point of the article is correct, in that volume and value of bad debt is far too high in an economic area said to be in economic recovery.