Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 4th of November 2016 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

In our recent article, Congress – The Art of Incumbency Part I, we reflected on the very poor and declining approval rating of the US Congress and the seemingly incongruous fact that members of both parties in Congress are serving more and more terms despite being liked less and less:

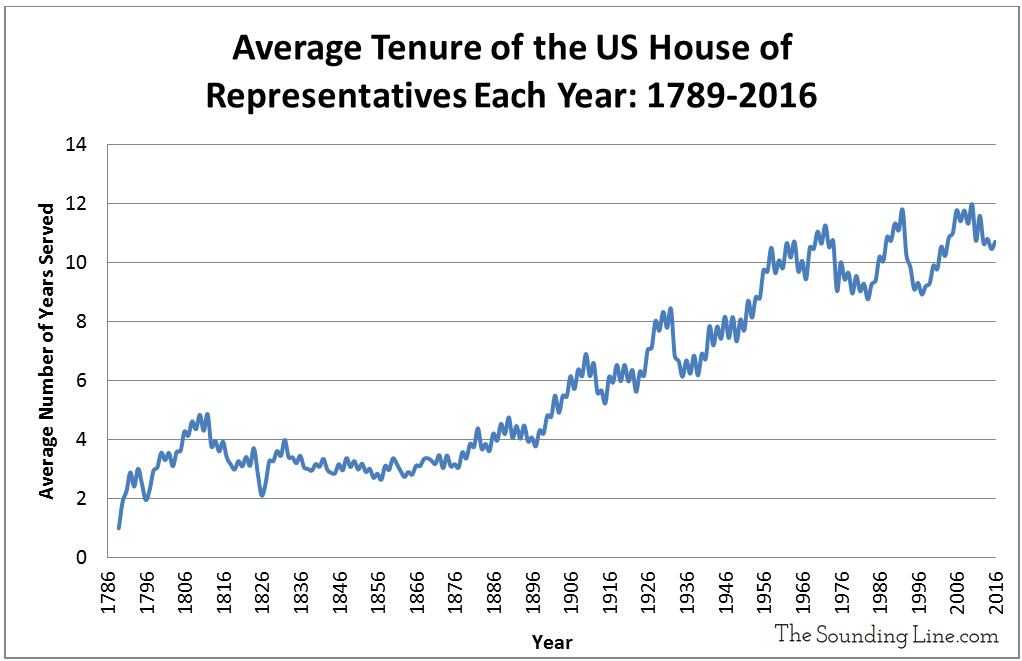

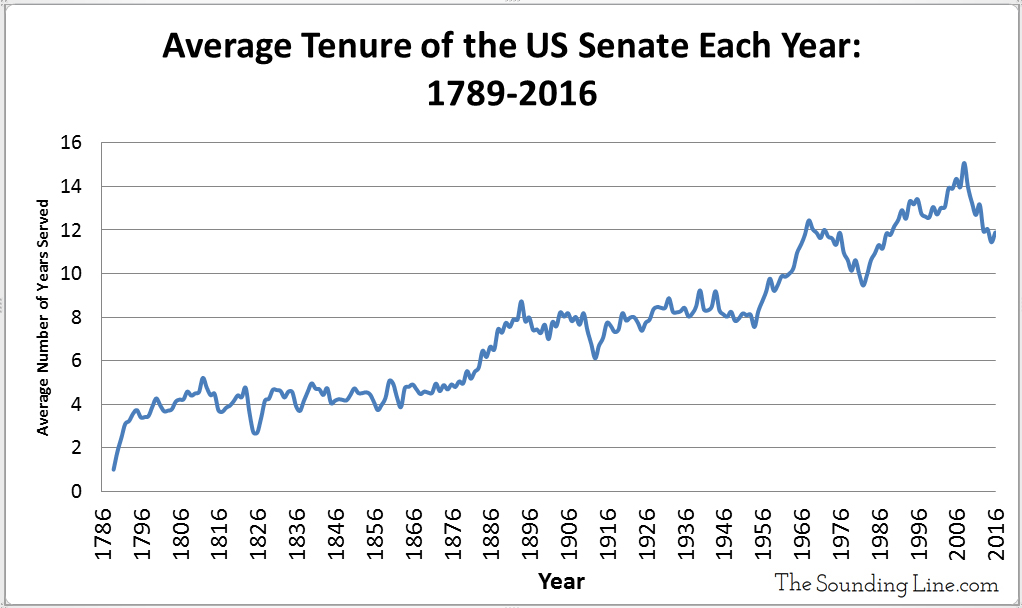

“Having accounted for the careers of over 13,000 Congress men and women, over a period of 227 years, we are able to chart the average years served, or ‘tenure’, of the House of Representatives and the Senate every year from 1789 until today.

As you might suspect, and as the charts below testify, there has been an unmistakable trend towards Representatives and Senators serving more and more terms. Until the start of the 20th century, the average years served in the House was typically less than four years, equivalent to less than two full terms. After that, the average tenure started to rise dramatically, hitting a high of 12 years or six full terms by 2008. The Senate follows a similar trend going from roughly four and a half years (less than a single six year term) for the first 100 years of American history to a high of 15 years (just less than three terms) in 2008.

While the average tenure has declined modestly since 2008, there is no indication that the long trend towards Congress members serving more and more terms is going anywhere. The current batch of Congress men and women are nearly the most ‘incumbent’ of all time.”

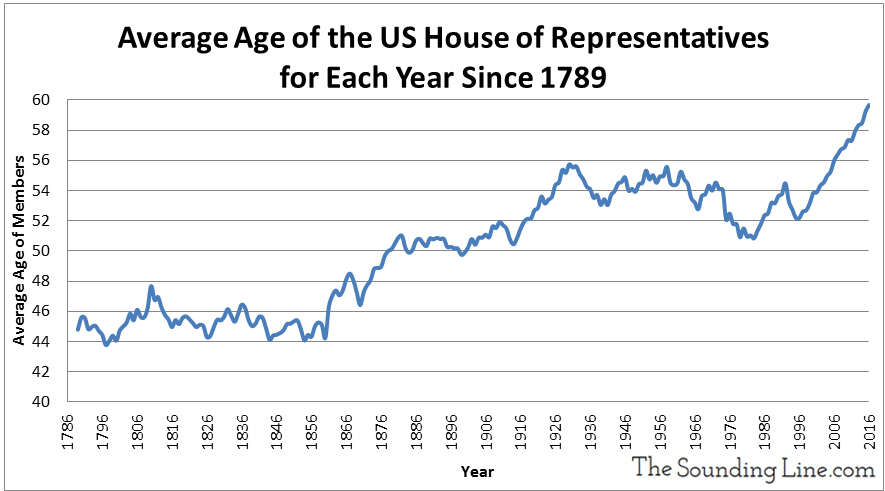

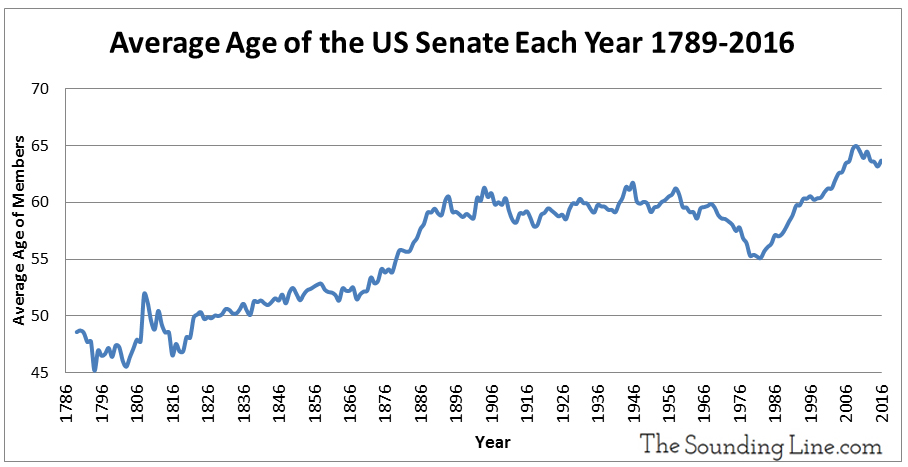

Drawing further on our database, the next question that sprung to mind was: “How has the average age of members of Congress changed since its inception?”

The two charts below show the average age of serving members of the House of Representatives and the Senate every year since 1789 (the few members whose birth dates are unknown were excluded). Both charts show the unmistakable trend toward an older and older Congress. Since 1996, the average lifespan in the US has increased by slightly less than two years and the median age in the US increased by roughly three years, yet the average age of the House of Representatives increased by nearly eight years and the average age in the Senate increased by more than four years.

It would be baseless to say that seniority should be viewed as an exclusively negative attribute. There have been great leaders much older than 65 who have benefited from the seniority and experience afforded by age. Yet, when taken within the context of Congress’s dismal track record and rock bottom approval rating, and given the fact that members of Congress are serving for longer and longer, the aging of Congress does not seem emblematic of a healthy institution.

P.S. We have added email distribution for The Sounding Line. If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

I think the increasing age is a subset of the longer tenure and not the other way around. That is, the longer tenure is not occuring just because the Senators are living longer (and thus stating in office longer) but that they are staying in office longer allowing for the greater age. If you look at the ante-bellum years of the Republic you see that the average tenure of Senators was only 4 years. In fact, only 1/3 ever stayed the full 6 year term. And it wasn’t because they were die in office! It was because they resigned after… Read more »

I agree with your statement. The aging of Congress likely has more to do with increasing terms served than the other way around. The increasing incumbency is the root problem. Aging is a significant secondary concern nonetheless.

Thanks for your interest!

What would be great if is you could send out a histogram of the current house and senate ages. I’d enjoy getting a better understanding of the distribution.

Thanks in advance.

I didn’t forget about this. It’s on my list

It would be interesting if you overlapped the pay and benefits values. Maybe a factor such as senator pays over public average wages, adjusted for inflation. I mean, its such a cushy job anymore it seems. Plus pensions.

I will look into it

Some years ago, I read that there was a higher degree of turnover in the Soviet Politburo, than there is in the US Senate. (From memory, incumbents are re-elected 92% of the time, unless they retire).