Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 3rd of July 2016 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

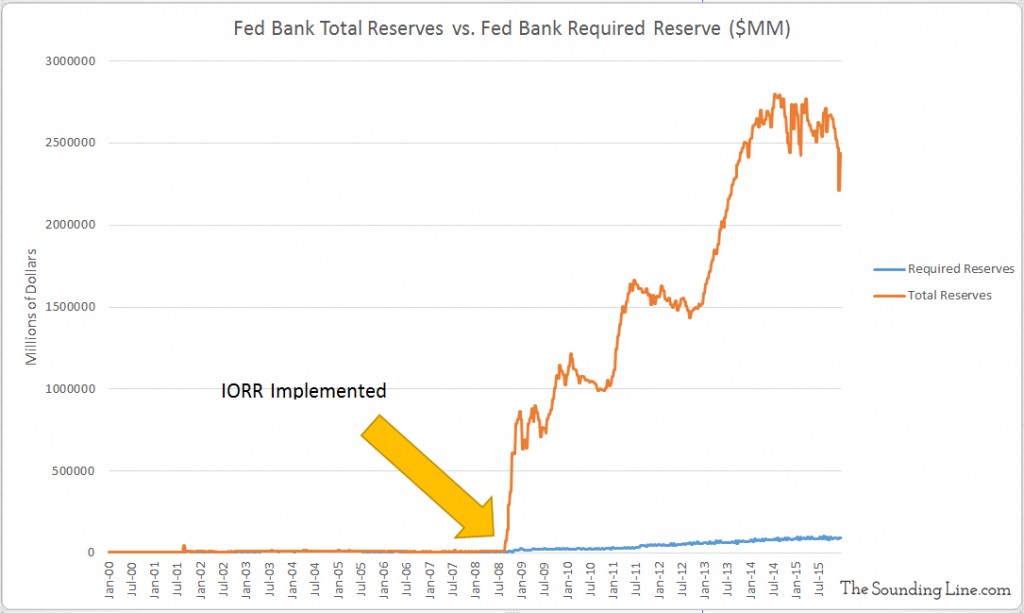

Back in February 2016 we posted an article, Negative Interest Rates – The Excess Reserve Overhang, that warned that the excess reserves being held by banks at the Federal Reserve posed a serious inflationary risk to markets. Over a year later, the issue of excess reserves is now being discussed broadly and with much more angst. Let’s take second look at the subject.

Back in 2016 we noted:

“The series of Quantitative Easing (QE) programs that were initiated during and long after the financial crisis were intended to… rebuild the banks’ reserves (and to suppress interest rates). The Fed accomplished this by buying securities, i.e. treasuries, from the banks. By doing so the Fed re-liquefied the banks’ coffers to the tune of $3.5 trillion (link here). Freshly flush with QE cash, the banks had much less need to borrow reserves from each other. This risked driving the Fed funds rate even lower than the Fed wanted. So the Fed did something new; they instituted a policy of paying banks interest on bank reserves kept at the Fed called the Interest on Required Reserves (IORR) and the Interest on Excess Reserves (IOER) (IORR and IOER are the same rate and used interchangeably here). They decided to pay a rate equal to the upper limit of Fed funds target rate. The Fed wanted the Fed funds rate to be between 0% and 0.25% so the IORR and IOER were set at 0.25%. The effect of this policy is that banks have no incentive to loan out their reserves for less than 0.25% because they would be forfeiting the IOER on those reserves and thus lose money. This had an important side effect that the Fed apparently also liked. It encouraged the banks to hold much greater amounts of reserves at the Fed.”

At the time, several European countries were experimenting with negative interest rates and we reasoned in the same article that these excess reserves posed a serious inflationary risk if negative interest rates were adopted in the US:

“Implementing a negative Fed funds rate may not be possible without eliminating the IOER. After all, the very point of the IOER was to keep rates above zero. Eliminating the IOER would eliminate the primary reason banks are keeping $2.34 trillion in excess reserves at the Fed. Without the IOER, and more importantly, if the IOER were to go negative, the banks would finally move the $2.34 trillion in excess reserves out of the Fed and into the real economy. Before assuming that this is a good thing, remember that the QE programs spent $3.5 trillion dollars over six years of which it appears that only $1.16 ever made it into the U.S. economy. A 0.25% or 0.5% decrease in the Fed funds rate could release $2.34 trillion in excess reserves into the real economy in a comparatively short period of time.”

Fast forward to today and, while the likelihood of negative interest rates has subsided, the risks that excess bank reserves pose to the economy remain as we described them.

Since 2016, the Fed has raised the Fed Funds Rate to 1-1.25%, and in a continued effort to keep excess bank reserves from spilling back into the economy, they have raised the IOER rate to 1.25%. This means that the Fed, and by extension the US taxpayer, is now paying the world’s largest banks approximately $27 billion dollars a year for taking zero risk and providing no useful services to the economy. That amount could rise to $64 billion if rates rise to just 3%.

The Fed appears to be trapped in a “lose-lose” situation. They claim that they are trying to tighten liquidity conditions in the economy. Yet, if they stop paying banks increasing sums of money on their excess reserves, those very same banks will look elsewhere for returns and might inject trillions of dollars of liquidity back into the economy by using excess reserves to purchase securities or through lending, undermining the Fed’s attempts to tighten. Because banks lend on a 10-1 fractional reserve basis, $2.1 trillion dollars in excess reserves could theoretically become $21 trillion in market liquidity. Though it is unlikely that all this money would be lent out, if it were, that would nearly double the current liquidity in the financial system (~$12 trillion). The effect would be a replay of the Fed’s QE programs only even more powerful and much more inflationary. Needless to say, that is the opposite of what the Fed wants at this moment.

On the other hand, the Fed has now acknowledged the horrible optics of paying banks increasing tens of billions of dollars so that those very same banks don’t undermine the Fed and crash the US economy. Just last week there was a congressional hearing discussing this and many of the associated issues we have discussed in the past year here at The Sounding Line. These Federal Reserve payments on excess reserves are essentially taxpayer money. The Fed pays the US treasury most of the profits that result from its actions, so money diverted to pay banks reduces the Fed’s payments to the US government. At the end of the day that means that US taxpayers have to make up the difference in the Federal budget. The Fed currently pays about $100 billion to the US government a year. Rates wouldn’t have to rise too high before that number would turn negative.

To make matters worse, the Fed also wants to reduce its own $4.4 trillion balance sheet of US treasuries and mortgage backed securities. Despite ending its QE programs, the Federal Reserve has maintained its balance sheet of assets purchased through QE. This necessitates continual purchases of treasuries and mortgage backed securities by the Fed as their holdings mature. Within the next year alone they will purchase about $250 billion in US treasuries. This is simply more liquidity, printed by the Fed, that is flowing into financial markets, contributing to record stock, and bond prices, and undermining their attempt to tighten conditions.

Purchases of this sort by the Fed have been going on since 2009 and, as a result, the Fed has become one of the largest purchasers of treasuries and mortgage backed securities in the world. If they stop buying, it could cause rates to jump and money to flow out of other financial assets such as stocks to make up the difference in demand.

Herein lays the Fed’s conundrum. They need to juggle three largely incompatible objectives: reducing their own balance sheet, reducing bank excess reserves, and reducing payments to banks without causing too much inflation, or too much deflation, or scaring financial markets.

As Dr. Michel of the Heritage Foundation described in his testimony to Congress, a combination of slowly selling the Fed’s assets and lowering the IORR at the same time may entice banks to use their excess reserves to buy the assets that the Fed unloads. Even without lowering the IORR, rising yields may entice banks to use their excess reserves to buy more securities. It is conceivable, perhaps even probable, that for a time this process could result in increasing liquidity flowing into financial assets if excess bank reserves decline faster than the Fed’s balance sheet. However, as the chart below shows, the Fed’s balance sheet is over $2 trillion dollars larger than excess bank reserves, so this proposal is not a complete solution if the Fed intends to completely eliminate its balance sheet. Surely balancing all of these forces while financial asset prices remain extremely overvalued by most metrics will be both tremendously difficult and involve very high risks.

The good news is that banks have begun to reduce their excess reserves from a peak around $2.7 trillion to $2.1 trillion. It is hard to know exactly what is prompting this and where that money is winding up (much is likely ending up in Treasuries). Nonetheless, the heavy lifting remains ahead. The bill for nearly a decade of highly experimental and controversial monetary policy is coming due.

The other good news is that discussions of reducing the Federal Reserve’s “mandates” are also increasingly in the news. All of this means that big changes are most likely coming.

P.S. We have added email distribution for The Sounding Line. If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any spam.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Thank you for the well written piece.

We live in interesting times….hedge accordingly.

That we do. Glad you enjoyed it.

great article. Have been searching for information on both the balance sheet issue and the IOER issue and this is the best I’ve seen yet.

The fed’s argument for instituting IOER/IORR makes very little sense to me-

with QE targeting 0%-0.25% anyway through QE (buying up treasuries from the banks), I really don’t get the logic behind thinking the fed funds rate would go below zero.

The Logic that all this accomplishes is promoting the banks to hoard cash – THAT makes sense to me. Am I missing anything?

Glad you enjoyed the article, thanks for the interest. This article from the Fed may help explain it. http://www.frbsf.org/education/publications/doctor-econ/2013/march/federal-reserve-interest-balances-reserves/ It says: “As the financial crisis deepened, Fed lending from the discount window soared, lending from the newly created liquidity facilities spiked, and excess reserves climbed into the hundreds of billions of dollars range, far exceeding depositories’ required reserves. In this situation, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York said that the Open Market Desk ‘…encountered difficulty achieving the operating target for the federal funds rate set by the FOMC, because the expansion of the Federal Reserve’s various liquidity facilities has… Read more »

Thank you, this does help make some sense of it. Whether it made sense to begin with.. maybe. But as rates continue to go up, I mean this can’t go on. We can’t have the fed paying interest on reserves if it keeps clicking up along with the federal funds rate.. 1.25% is already way too much.

Like the other poster said, interesting times.

Agreed. Any % is already too much.

Banks have gained control of the quarter ” point”? Each time it ticks up , banks get more windfall?

Exactly correct

Giving banks free money so they can (if they desire) buy the crap mortgages off the Fed balance sheet? Why can’t the Fed sell mortgages when hedge funds and sovereign wealth funds would pay a massive premium to participate?