Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 13th of August 2019 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe.

Italy has witnessed a historic economic retrogression over the last decade. As of the first quarter of 2019, Italy’s economy is still 5% smaller than it was at its peak in 2008 (as measured in inflation adjusted Euros).

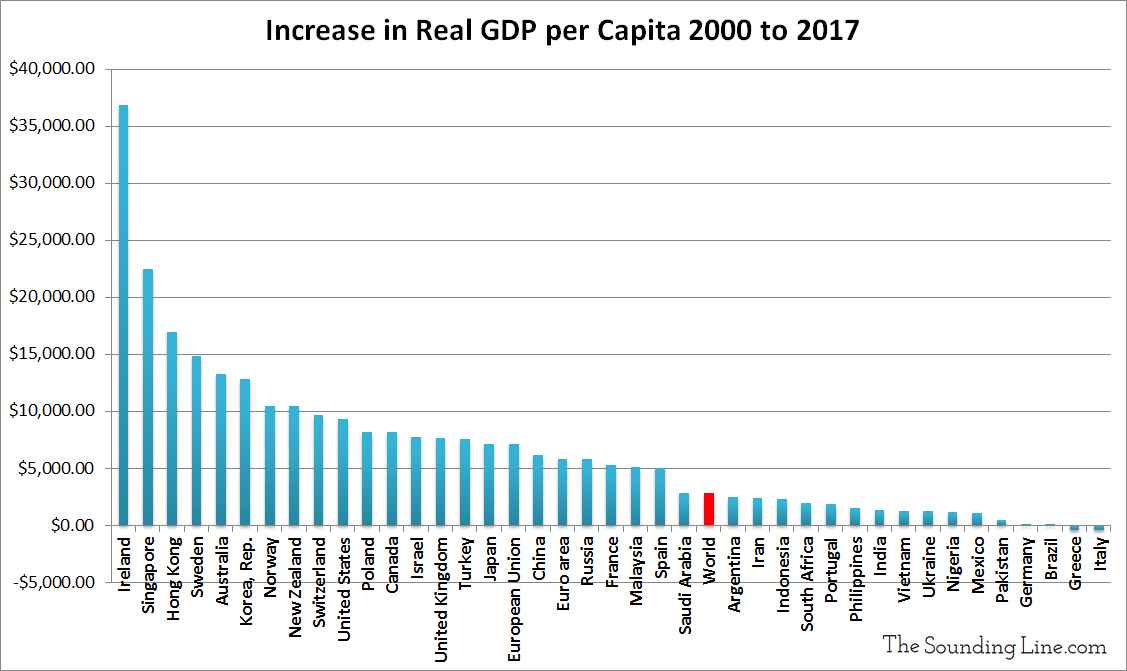

Since 2000, Italy’s economy has barely grown 1%. It’s the fifth worst growth rate among 181 countries around the world for which inflation adjusted local currency GDP data is available. Measured in inflation adjusted US Dollars, Italy’s economy is actually smaller than it was in 2000.

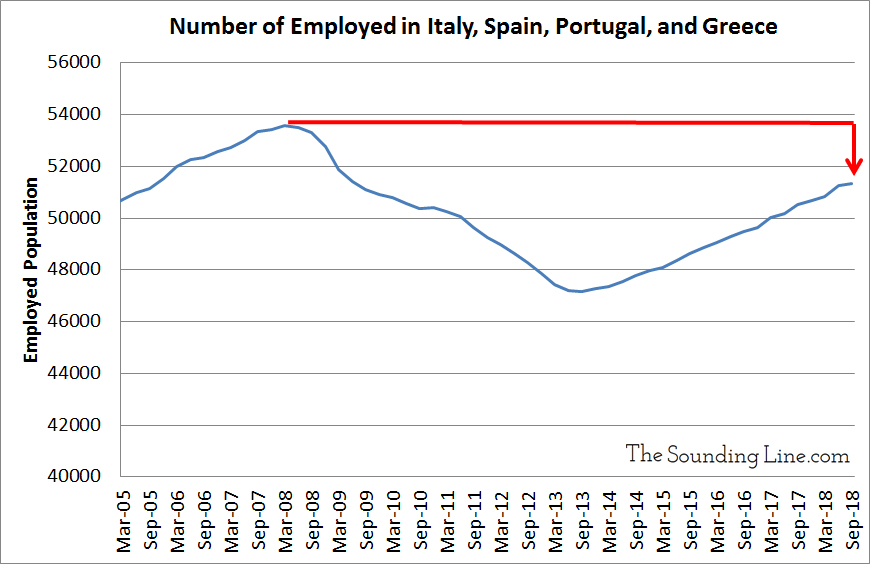

The number of people working in Italy, and Southern Europe in general, is still lower than it was before the Financial Crisis.

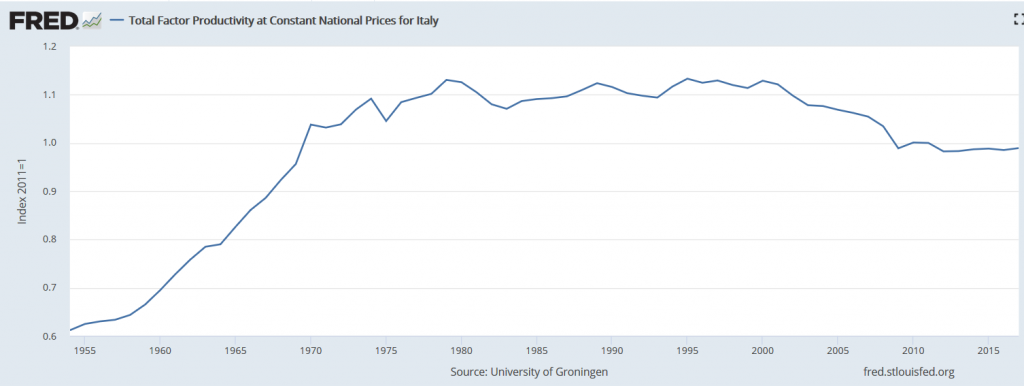

Italian wages have fallen dramatically and total factor productivity is below levels last seen in 1970.

Meanwhile, Italy has the fourth highest government debt level in the world, 132% of GDP, and the 10th highest non-performing loan ratio.

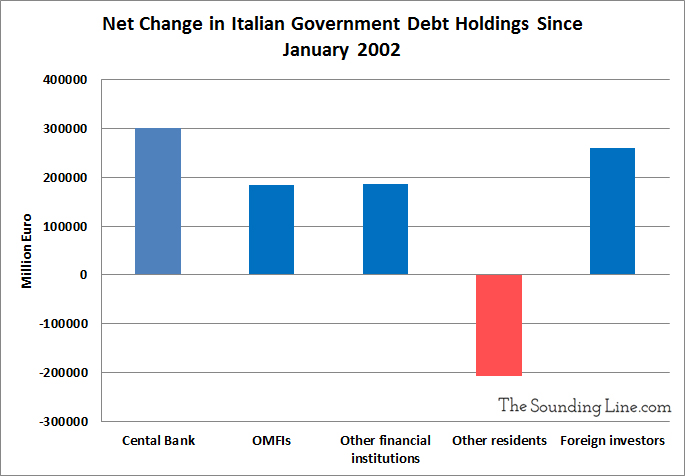

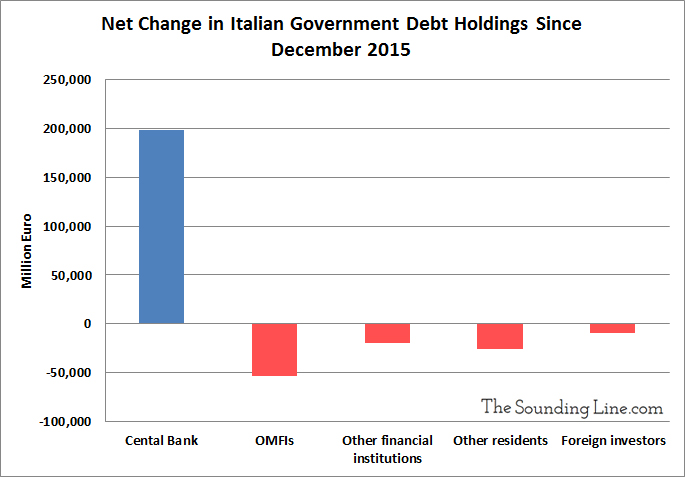

All of this is despite Italy being the largest single recipient of quantitative easing in the Eurozone. In fact, the ECB is now the single largest net buyer of Italian debt since the founding of the Euro.

How Did Italy Get Here?

Beyond the burden of having its currency, the Euro, priced according to Germany’s very different economic situation, Italy has the fifth highest overall tax burden in the world and the second highest payroll tax rate among developed economies. Italy ranks a dismal 79th for economic freedom, the second lowest in the developed world and below the likes of Kyrgyzstan. It ranks 49th for economic competitiveness, and 45th for business friendliness. Italy’s population is also among the oldest in the world, aging rapidly, and beginning to shrink.

What’s the Recovery Plan?

The current economic turn-around plan being pushed by Italy’s populist coalition government is a combination of tax cuts and increasing government spending: universal basic income, infrastructure spending, and lowering the retirement age to 62. In other words, the economic plan is to run large fiscal deficits for the foreseeable future.

There is no doubt that, all other things being equal, increasing deficit spending adds to a country’s GDP. The problem for Italy is that it hasn’t run a budget surplus in well over 30 years, it already runs a budget deficit larger than most countries in the Eurozone, and it is already one of the most indebted governments in the entire world.

Who is going to loan money to Italy to finance ever more deficit spending? Keep in mind the Italy’s coalition government is simultaneously talking about creating a parallel currency to enable a soft-default on its current debts. It is not surprising that, since 2015, the only entity that had been a significant net buyer of Italian debt has been the ECB.

If Italy had spent any part of the last 30 plus years bringing its fiscal house into order, it could conceivably use fiscal stimulus to turn around its faltering economy. Having already used fiscal stimulus for over 30 years without interruption, the idea that fiscal spending is now going to turn around the Italian economy is a pipe dream.

Italy expects that the ECB will continue to monetize its debts at whatever pace is necessary to keep Italian interest rates at historic lows. Performing QE as a temporary means to prop up financial markets during an acute recession is one thing. Doing QE as a permanent measure to finance otherwise unsustainable government spending is very different, and is likely to result in inflation and/or cross-currency deprecation that mitigates nominal growth benefits. It is a classic money-printing-to-finance-out-of-control-government-spending scheme that always ends badly, whether it be Revolutionary France, Wiemar Germany, or even the US during the 1970s.

Fiscal stimulus, much like monetary stimulus, is only really effective when it is counter-cyclical. Neither can be counter-cyclical when implemented in perpetuity. One must ‘save up’ fiscal and monetary policy potential during ‘good times’ so that it can be used during recessions. Italy has done nothing of the sort. Neither has the US, or most other developed economies.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.