Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 8th of August 2017 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

In nearly every major economy in the world, from Japan, to Europe, to the United States, government debt has rocketed higher in recent years. As we recently noted:

“Combined, the largest 50 countries in the world owe nearly $65 trillion. That is a staggering 90% of their combined GDPs! Such a figure is unprecedented. The majority of the 50 largest economies in the world have sovereign debt over 50% of GDP and eight have debt over 100% of GDP including two of the three largest economies in the world: the US and Japan.”

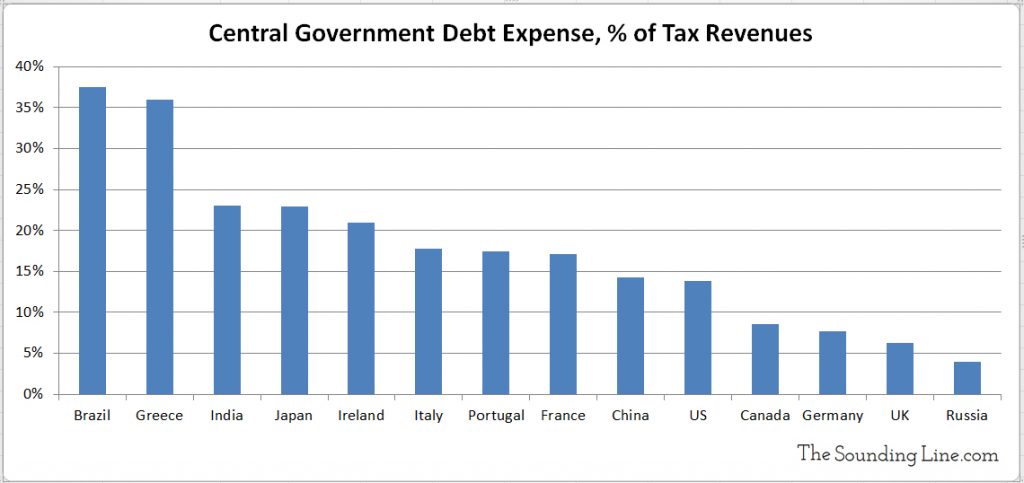

Governments around the world have been able to continue to service their growing debts without infringing on actual government services and entitlements, due to the current era of low interest rates induced by central banks and surging borrowing. However, in many countries, government debts have now become so large that the expense of servicing their debts is already consuming large portions of tax revenues, despite low interest rates. In order to illustrate this point, we have created the following chart, which shows the percent of central government tax revenue that is already being spent on servicing the debts of 14 of the world’s most important economies. Astoundingly, despite the lowest global interest rate environment in 5,000 years of recorded history, Brazil and Greece are paying over 30% of all tax revenues to service their debts. India, Japan, and Ireland are paying over 20%, and Italy, Portugal, and France are paying over 15%.

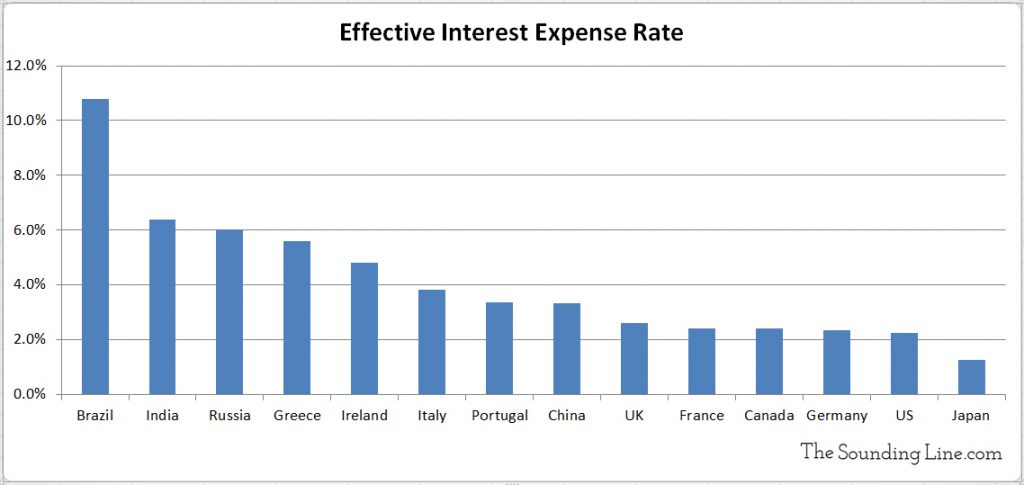

By dividing the total outstanding government debt by the current yearly debt expense, it is possible to determine the simplified ‘effective’ interest rate that these same countries are paying on their debt. As the chart below shows, only Brazil is paying a rate above 10%. Most countries are paying less than 4% a year, well below historically normal long term interest rates.

The scope of the government debt problem becomes clear from these two charts. Japan, for example, is paying nearly 24% of its tax revenues to service its debt, despite only paying an effective interest rate of 1%! Even a modest normalization of interest rates from 1% to 4% would consume 100% of current Japanese tax revenues.

How will it all end?

Central banks continue to suppress interest rates hoping that this will eventually boost lagging economic growth and inflation in these very same countries. The trouble is this: if low interest rates ever succeed in boosting economic growth, the inflation and rising interest rates that normally accompany such economic acceleration will send the already high cost of servicing government debt through the roof unless government spending is dramatically curtailed. On the other hand, if economic growth remains sluggish and government debt continues to grow, even without rising interest rates, interest expenses will consume ever increasing portions of tax revenues, necessitating ever increasing government borrowing, compounding the inevitable problem of what happens when interest rates eventually rise even the slightest amount.

The further trouble for most countries on this list is that government spending and employment have become such an important part of their efforts to revive their economies (and curry favor among voters) that significant spending cuts would be economically self-defeating or politically impossible.

Either these countries’ economies recovery quickly and governments make deep cuts to entitlement programs and spending, or many of these countries are likely to face sovereign debt crises and the default or hyperinflation that accompanies them.

P.S. If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

You area assuming that Gov debt interest payments are immediately sensitive to interest rate changes – only new borrowing will attract higher rates, as previously issued debt will continue at the coupon it was issued at. So if there is anyone forward-thinking in Gov Treasury right now & they can issue 100yr at 0.5% to fund new borrowing (budget deficit and maturity roll-over) the interest on those bonds are low and fixed for 100yrs. Problem is if budget deficits are not gotten under control AND markets start asking for 1%, 1.5%, 3%…on new issues – then the problem begins, but… Read more »

You are correct. I am assuming that the government continues to run a deficit and therefore must issue new debt. History says that that is a very safe assumption but if the deficit is somehow eliminated it would eliminate the risk of future rate increases. One can hope…

Thanks for the interest!

Hello,

I was wondering if you could post the source for these calculations? They don’t seem to align with the worldbank data?

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/GC.XPN.INTP.RV.ZS

Thanks!

Josh

Josh,

I believe the interest expense numbers came from https://www.nationaldebtclocks.org/

The tax revenues came from individual queries for each country and thus come from a variety of sources, as I was unaware of the worldbank data set when I wrote the piece in 2017.

At this point, I would default to the World Bank data

I’ll try and do an updated post