Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 25th of October 2018 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe.

Ever since central banks’ initiated their campaign of extremely accommodative monetary policy a decade ago, critics have been warning that it was a dangerous idea. They warned that continuing negative interest rates and quantitative easing for years after the recessions had passed would lead to miss-allocations of capital, moral hazard, asset bubbles, wealth division, and complacent investors. Critics warned that the policies would mask the need for real pro-growth structural reforms and destroy price discovery mechanisms. For years, critics have pressed central banks to normalize policy while the times were good, lest they have no tools and no ammunition to fight the next recession when it inevitably arrives.

It appears that the critics were right.

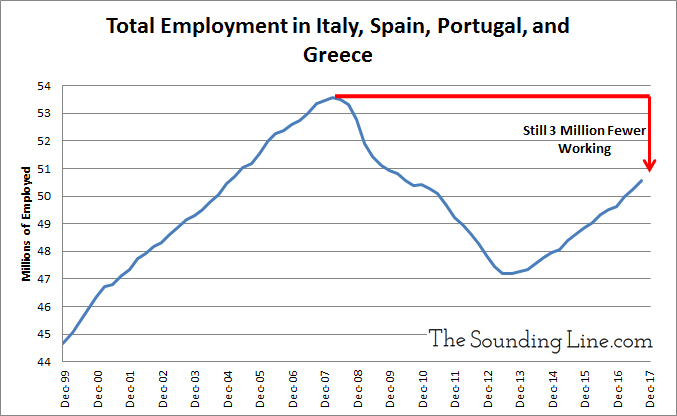

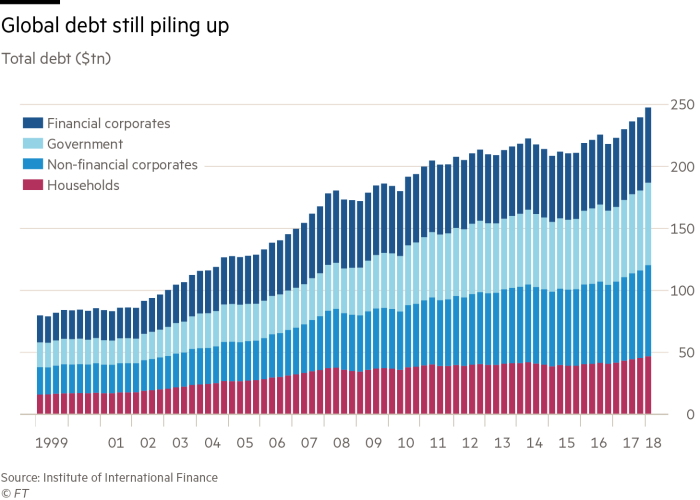

Since 2008, the world has witnessed the largest buildup of debt in modern history. The search for yield in a negative interest rate environment has pushed trillions of dollars of debt into emerging markets that didn’t have the means to support it, companies that never turned a profit, and governments that don’t use it productively. With few exceptions, labor markets have become less flexible, taxes have risen, regulation has tightened, and fiscal discipline has gone out the window. The torrent of cheap money allowed emerging markets like Turkey, South Africa, Brazil, and the Philippines to paper over weak institutions, corruption, and autocratic tendencies. The non-performing loan problem that contributed to the Eurozone’s last crisis is still many times larger than it was in 2007. Southern Europe’s labor market is still yet to recover to pre-2008 levels. These problems are now coming home to roost, economically, socially, and politically.

Perhaps the worst perpetrators of excessive monetary policy have been the ECB and the BOJ. Both central banks are still holding interest rates at negative levels and are still expanding their balance sheets, albeit at a reduced pace. They have monetized huge portions of their domestic economies and cannibalized their sovereign debt markets. The ECB has been the only net buyer of Italian government bonds for several years and is now the largest net buyer since the Euro was created. The BOJ has so thoroughly taken over the Japanese government bond market that days frequently go by without a single trade. Having destroyed that market, the BOJ moved on to equities. They are now a top ten shareholders in 40% of Japanese stocks. Once the bulk of real investors have been displaced from a market, continuing to monetize that market serves little real world purpose. That point of diminishing returns has been reached in many of the most critical markets around the world.

It has been a decade since the global financial crisis and years since the Federal Reserve began tightening monetary policy in the US. Finally, amid slowing global growth, rising inflation, and a string of bona-fide bear markets around the world, the BOJ and the ECB have signaled an intent to eventually stop expanding their balance sheets. Talk about bad timing.

The ECB and the BOJ missed an entire decade-long tightening cycle and now face the possibility of a recession without traditional monetary policy tools at their disposal. Lowering interest rates further will do little and, having already displaced the bulk of investors from of their sovereign debt markets, re-accelerating QE is not going to have the same effect as it did in 2009. Furthermore, because the Fed has been slowly tightening policy for years and because the US economy has finally received some degree of regulatory and tax reform, the sort of synchronized global monetary response that occurred in 2008 will be harder to execute today. Imbalances in monetary policy and growth mean that currency risk must now be taken seriously, significantly constraining their policy options. Perhaps most concerning of all, while the Eurozone’s growth is slowing, its inflation is rising. Even if the ECB had normal policy tools at their disposal, which they don’t, the convergence of these trends would be a nightmare to deal with.

Whether the weakness that global markets have been enduring this year is the prelude to a recession or just a prolonged correction is unclear. Either way, it forces one to contemplate the perfectly plausible scenario of slipping into a recession with powerless central banks and badly distorted markets. It would be a perfect storm.

If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Both the Euro and the yen are way over valued. With a government gross debt to GDP ratio of 253 percent, Japan has the unwanted title of ranking highest in the developed world. The recent budget requests by Japan’s central government ministries and agencies for fiscal 2019 total a record-high 102.77 trillion yen.

Japan’s trade balance has again swung into deficit territory and a matter that has not garnered enough attention is how the economic problems that continue to develop in China will most likely spill over and affect Japan. The article below delves into these issues.

http://brucewilds.blogspot.com/2018/10/japan-end-of-third-quarter-update.html