Submitted by Taps Coogan to The Sounding Line on the 26 of January 2015

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

In Part I of the ‘The Euro – Help or Hindrance’ (link here), we contrasted the trends in a few key economic indicators for Germany as compared to France, Italy, and Greece since adopting the Euro currency in 1999. We saw that France, Italy, and Greece’s economic performance has been weak particularly when compared to Germany’s.

In Part II we ask the question:

How has the economic performance of the early Euro adopters been compared to European countries that chose to maintain their own currencies?

Adoption of the Euro currency first began in 1999 by Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain. Of the 28 members of the European Union others have gone on to adopt the Euro currency at later dates.

In contrast some countries in the E.U. have chosen to maintain their own national currencies. These countries are Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

It should be noted that Denmark nominally maintains its own currency but has pegged it to within 2.25% of the Euro. This makes it a bit tricky to group but at least it has 4.5 degrees of fiscal independence…

Other major Western European countries; Norway, Switzerland, and Iceland are neither in the E.U. nor adopters of the Euro. Croatia, which is currently an E.U. member and hasn’t adopted the Euro, joined the E.U. in 2013. For the purposes of this analysis, which spans 1999-2014, Croatia will be considered a non-E.U. country like Norway, Switzerland, and Iceland.

Putting this together we will compare three categories:

- Countries that adopted the Euro in 1999 (Euro Founders): Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain

- Countries in the E.U. that have not adopted the Euro (E.U. non Euro): Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Sweden, and the United Kingdom

- Western European countries that have neither joined the E.U. nor adopted the Euro (Non E.U.): Croatia, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland

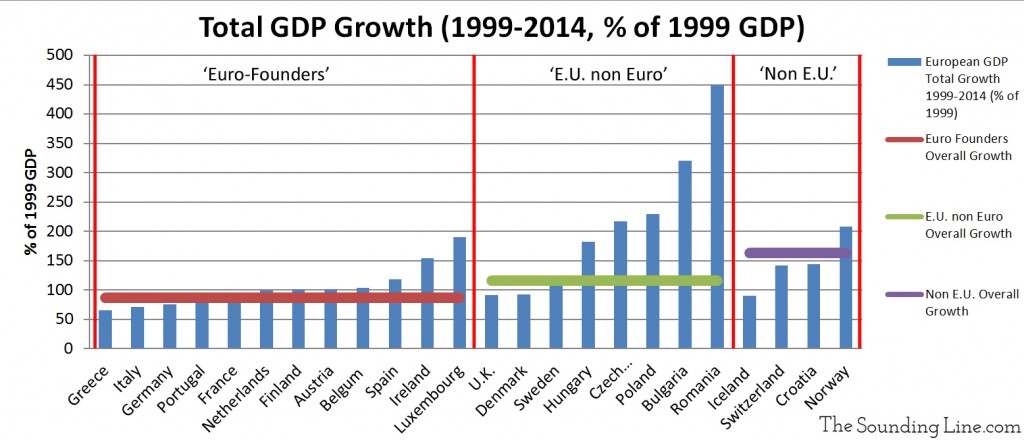

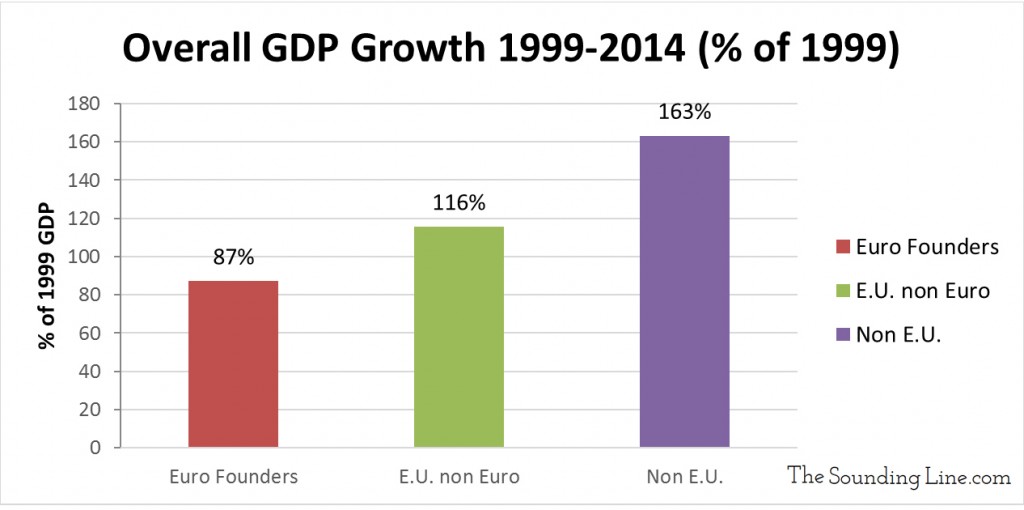

The first metric that we will examine is the total GDP growth from 1999 to 2014 as a percentage of the 1999 GDP for each of the target countries and for each of the categories listed above.

From the two charts below a number of important observations become apparent. First, we find that the countries which adopted the Euro currency in 1999, the ‘Euro Founders,’ experienced 87% overall GDP growth. That represents the poorest performance throughout this period. The countries in the E.U. that have not adopted the Euro, the ‘E.U. non Euro,’ have done better with 116% growth and those countries which stayed out of the E.U. entirely have done the best with 165% GDP growth. We can see from the charts below that every single country outside the ‘Euro Founders’ group has had growth above the overall growth for the ‘Euro Founders’ (the lowest being Iceland at 91% compared to 87% for the ‘Euro Founders’). These two charts make a fairly compelling case that the Euro is not helping its adopters maintain competitive GDP growth. It’s also clear that Iceland, Switzerland, Croatia, and Norway have grown robustly when compared to their E.U. neighbors.

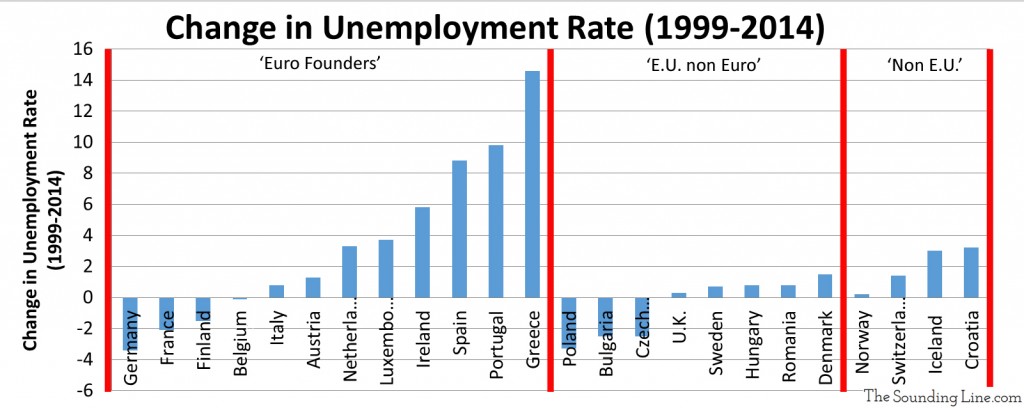

The next comparison is the change in unemployment rates for the same countries and categories.

The chart below shows the difference in the unemployment rate in 1999 and in 2014 for each country. Positive numbers indicated that the unemployment rate went up (poor performance) and negative numbers mean the unemployment rate went down (improved performance). One can see very clearly that all of the worst performing countries were in the ‘Euro-Founders’ group; Luxembourg, Ireland, Spain, Portugal, and Greece. To contrast this, Germany, France, and Finland showed some notable improvement. Nonetheless, in Part I (link here) we noted that France recently declared an ‘economic state of emergency’ because their unemployment rate has climbed back up to 10.6% and has remained persistently above 10%. The ‘E.U. non Euro’ countries performed much better with a few countries showing improvement and a few showing moderate increases in unemployment. None of the ‘E.U. non Euro’ countries come close to the worsening performance of the ‘Euro Founders’. The ‘Non E.U.’ group all saw some moderate worsening in unemployment, though again, nothing to the scale of the worst ‘Euro-Founders’.

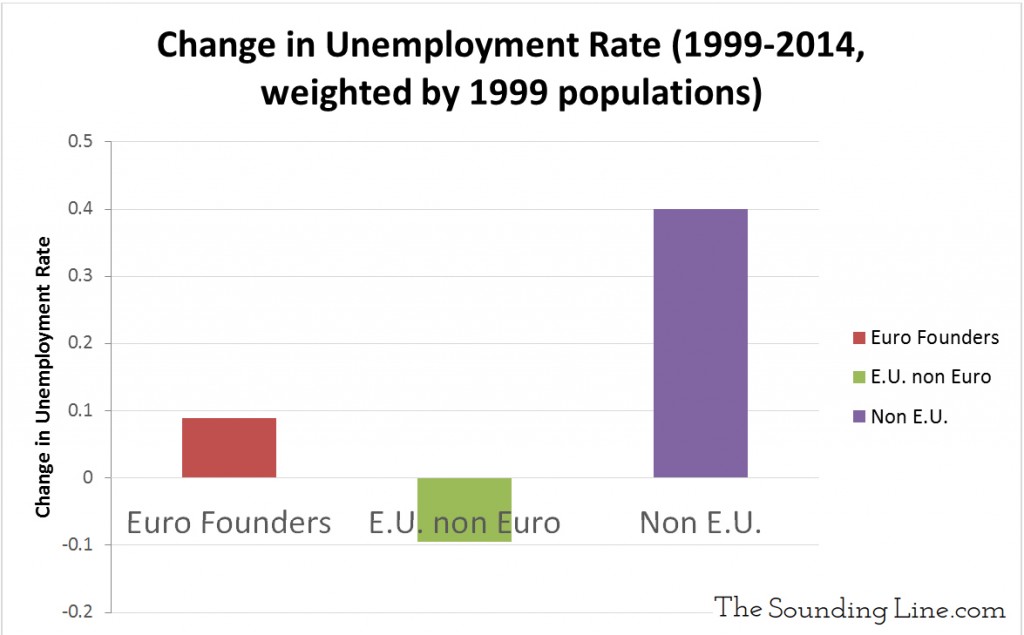

The chart below shows the overall changes for each category. To determine the overall changes fairly the changes were weighted by the population of the countries in 1999. For the ‘Euro Founders’ group the overall change has been a small increase in unemployment. The improvements in populous Germany and France largely offset the bad performance of smaller countries like Greece and Portugal. This belies the very profound divergence that occurred among the early adopters of the Euro which can be seen in the chart above. In contrast, the ‘E.U. non Euro’ category showed a slight improvement. The worst performer was the ‘Non E.U.’ category. All of the countries in the ‘Non E.U.’ group experienced some moderate worsening in unemployment.

In Summary:

When we take all of these charts together a picture begins to emerge. Those countries which adopted the Euro in 1999 have seen the slowest GDP growth and an overall increase in unemployment. There is a very stark divergence between ‘strong’ countries like Germany and nearly everyone else. The E.U. countries that have maintained their own currencies have experienced significantly higher GDP growth and an overall decrease in unemployment and importantly, more homogeneous performance than the countries that adopted the Euro. The countries which chose to stay out of the E.U. completely have seen the largest GDP growth but have all witnessed some modest increase in unemployment.

In ‘Part I’ (link here) we saw that there was a clear divergence between the strong economic improvements experienced by Germany and those of France and Italy, the next largest Eurozone economies, and Greece as well. When we combine this with the realization that the overall GDP growth has been slower for the ‘Euro Founders’ as compared to those E.U. countries that have maintained independent currencies, serious questions arise about whether the Euro is a help or a hindrance.

In ‘The Euro – Help or Hindrance – Part III’ we will discuss why the Euro system is fundamentally flawed and why relatively small Eurozone countries keep threatening the stability of the entire global financial system.

Stay tuned!

P.S. We recently added email distribution for The Sounding Line. If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

In order to fully evaluate and frame the base question of whether the euro has helped/hindered the European Union, should we start with the base question of “what was the purpose of the euro?” The statistics sure seem to point towards it being a potential hindrance for some countries, but would the financial crisis of the past ~8 years have been that much worse for the members of the EU were the euro not established? Would the countries who display the most negative trends have seen their currencies spike into runaway inflation, or would they have collapsed or suffered other… Read more »

Thanks for the observations and great questions The question of ‘what was the purpose of the euro’ is a good place to start but a difficult one to answer without bias. From a political sense, the Euro was conceived as an instrument to further European integration into the E.U. I am sure the idea was that having a common currency would encourage member countries to be co-operative and cohesive with an added benefit that it makes it much more complicated for member countries to leave the E.U. In an economic sense, many smaller countries on the peripheral of Europe were… Read more »

Thanks for the quick reply, good insight. I’m really interested in this part:

“As we will discuss in depth in Part III that is a key part of what creates systemic problems in the Euro, namely creating a disconnect between a country’s real economic health and the provision of a stable currency and cheap debt. This combination destroys an important feedback loop and allows leaders to postpone important economic reform because cheap debt and a stable currency remain despite ineffective economic policy.”

…i.e. politics and human nature clashing with sound decision making. Keep up the good work!

Part III is now up. Hope its provides some useful further explanation.

Thanks!

[…] Second the E.U. countries that first adopted the Euro have experienced slower growth and deteriorating employment compared with the European countries that have maintained their own currencies (Part II here). […]