Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 16th of April 2020 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe.

As we have noted on a number of occasions, the Federal Reserve has launched what is arguably the largest monetary stimulus program in the nation’s history. Not only has the Fed pushed overnight rates back to zero, the entire treasury yield curve has dipped below 1% for the first time ever. All but the 30-Year still remains under 1% at the time of writing.

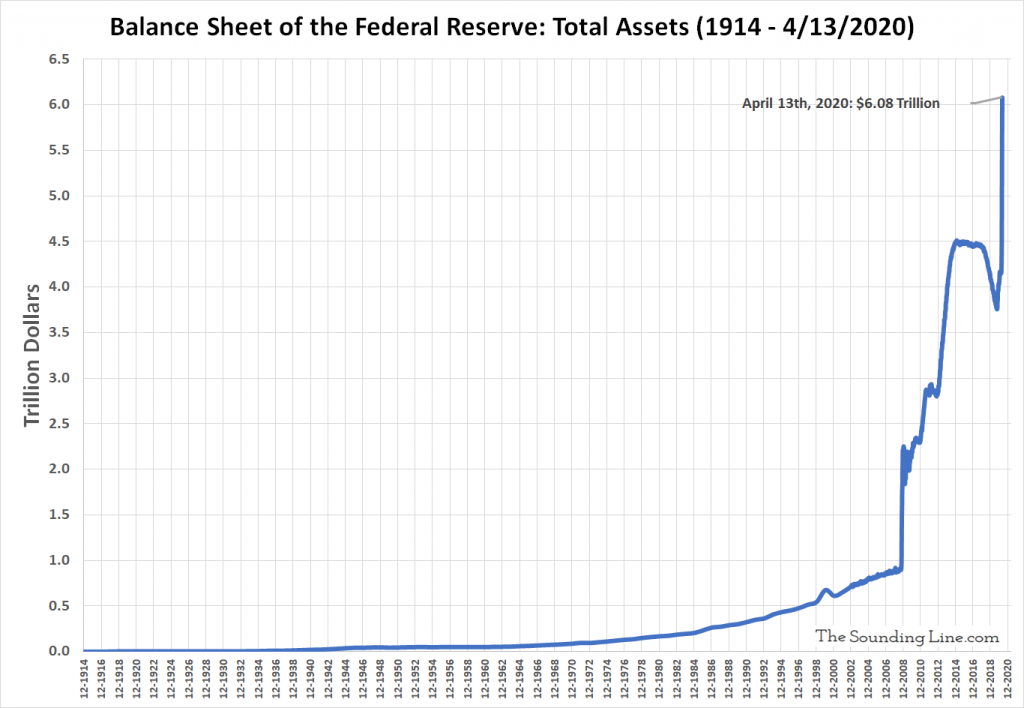

Meanwhile, the Fed’s balance sheet has grown by nearly $2 trillion since the outbreak started, dwarfing its initial response to the Global Financial Crisis. The Fed and its ‘Special Purpose Vehicles’ are now printing money and buying or borrowing: treasury securities of all maturities, repos, mortgage-backed securities, commercial mortgage-backed securities, commercial paper, corporate bonds, junk bonds, investment grade bond ETfs, and junk bond ETFs.

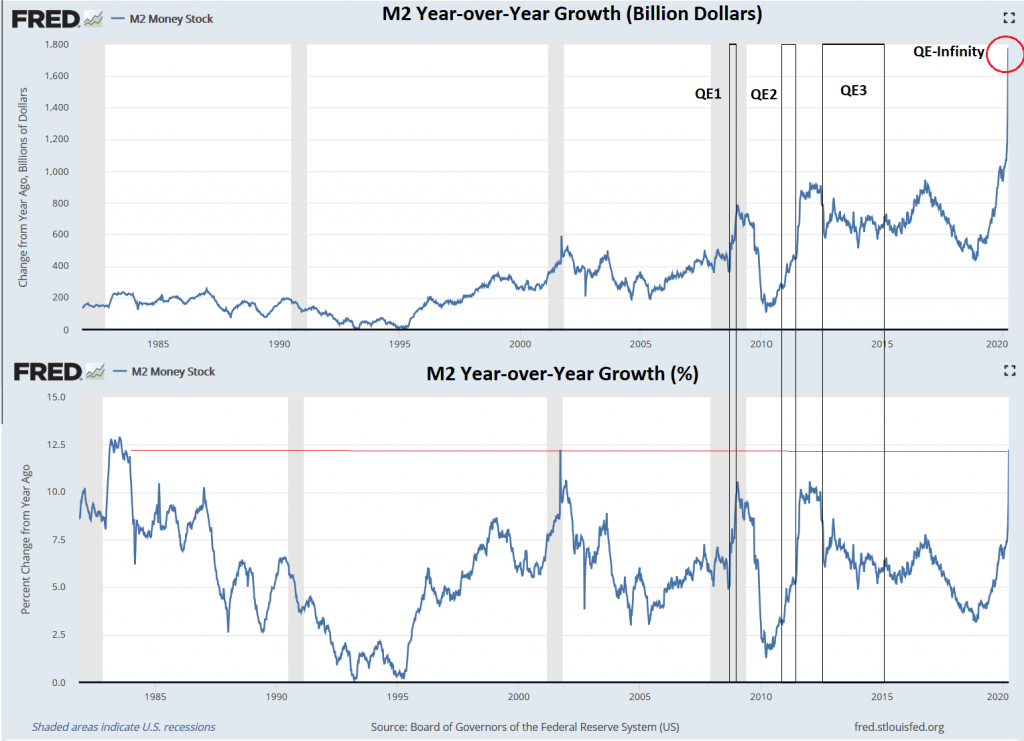

The net result is that the money supply in the US has surged by its largest amount on record, by far, and is growing at a year-over-year pace that was last seen when inflation was peaking at over 10% in the early 1980s.

All of which begs the question: how will the Fed normalize monetary policy after the crisis passes?

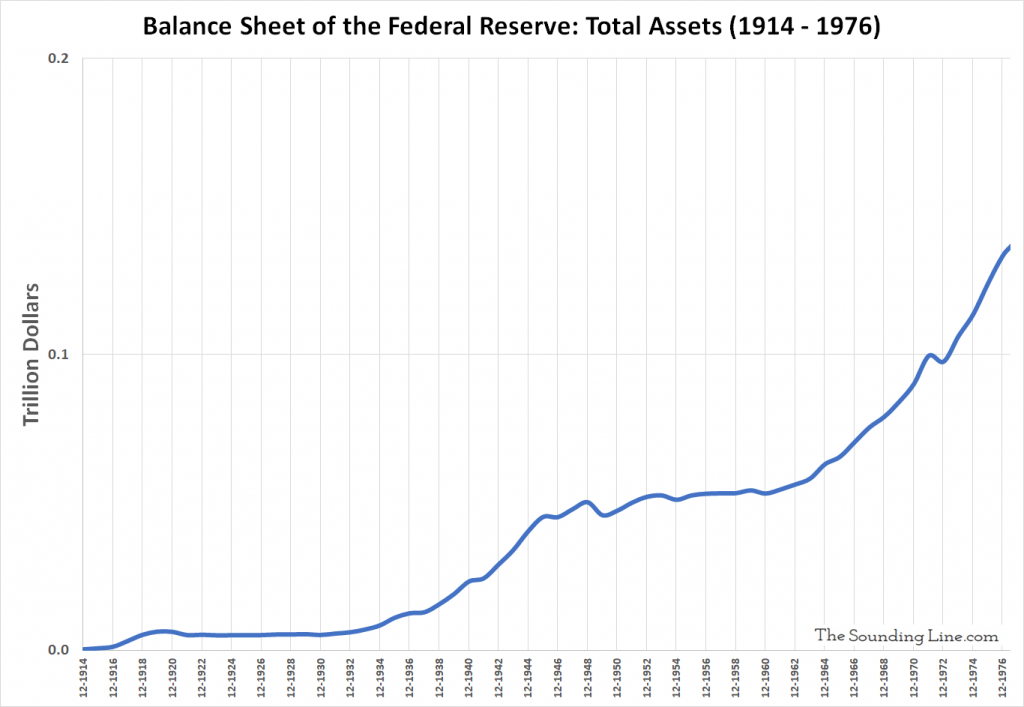

The problem with imagining the Fed reducing its balance sheet to where it was just a few months ago is that, since it’s founding in 1913, Fed has never succeeded in reducing its balance sheet for more than a matter of months.

Indeed, the only real attempt that the Fed has ever made to reduce its sheet balance sheet by a large percentage was in 2018 and early 2019. That still fairly modest reduction, about 15%, resulted in a massive selloff in markets in late 2018, a sharp slowdown in the industrial economy in 2019, and a blowout in repo markets that forced the Fed to resume balance sheet expansion by September of 2019.

The Fed’s failed attempt to reduce its balance sheet in 2019 occurred despite very strong economic growth, a record long bull market, low interest rates, record consumer optimism, record employment, and it followed shortly after record large corporate tax cuts.

If the Fed wants to have the same tailwinds when it attempts to normalize after this crisis, it is going to have to wait a very, very long time.

While its waiting, the Fed’s balance sheet is likely to remain historically large, both in dollar value and relative to the economy.

Inflation Coming?

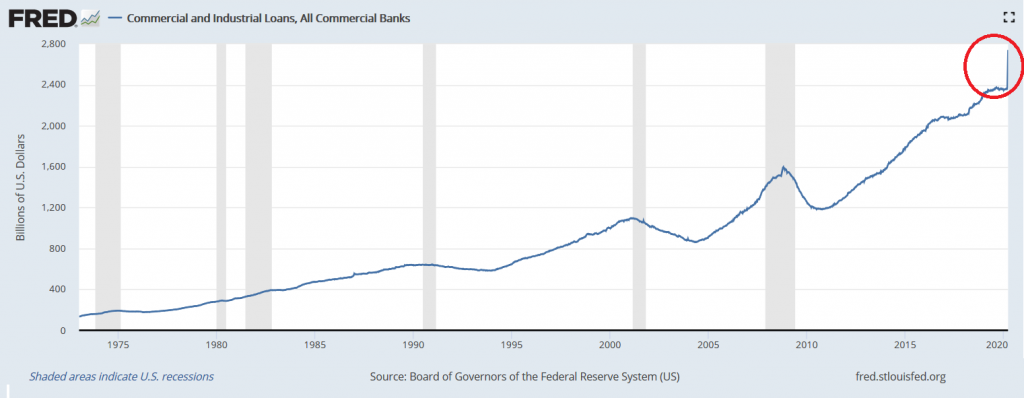

An often overlooked factor that prevented the Fed’s past QE programs from causing more inflation was that they coincided with a huge expansion of banking regulations. Those regulations (and the IOER policy), led the banks to massively increase their reserves. That meant that the large majority of the extra liquidity that the Fed created through its QE programs ended up being parked at the Fed itself. Critically, the liquidity did not create the potential for a significant acceleration of bank lending and, therefore, had limited effects on the endogenous money supply.

The current jump in the Fed’s balance sheet is very unlikely to be accompanied by stricter bank regulations. To the contrary, reserve requirements are being suspended and all efforts are being made to get as much credit into the economy as possible. Indeed, commercial and industrial lending has spiked by the largest amount on record, by far.

Observably, the Fed’s current QE-Unlimited program is having different and more powerful effects on lending and the money supply than its past QE programs. Once this crisis passes, I suspect that it will have a materially different effect on inflation too.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Hi,

Is it possible to have the FED balance sheet in csv?

Available on FRED but not before 2000 🙂

Thanks