Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 18th of September 2019 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe.

Advocates of negative interest rates and large public deficits often point to Japan as an example of a developed economy that has endured both conditions for decades without succumbing to an acute economic crisis. Such advocates contend that other countries can follow Japan’s lead and use negative interest rates and deficit spending much more aggressively without worrying about negative side effects like inflation.

Such advocates are wrong.

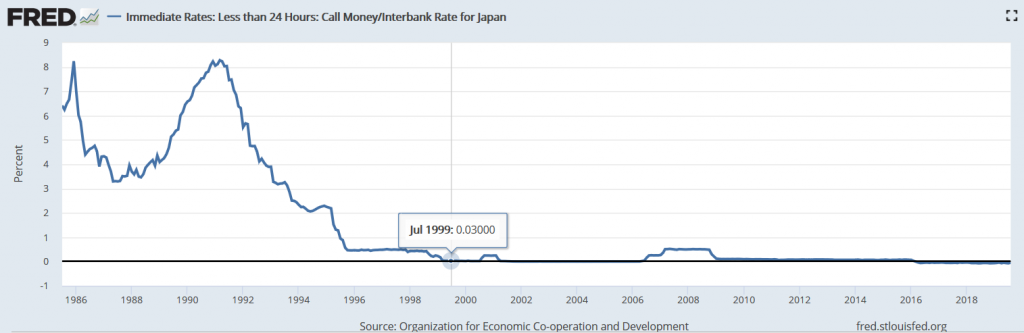

The Bank of Japan first cut it’s overnight interbank rate to zero in early 1999 after the Japanese property market collapsed. With a couple of brief exceptions, rates have remained at-or-below zero ever since. Today, Japanese interbank overnight rates are -0.045% and likely heading lower.

Japanese Interbank Overnight Rates

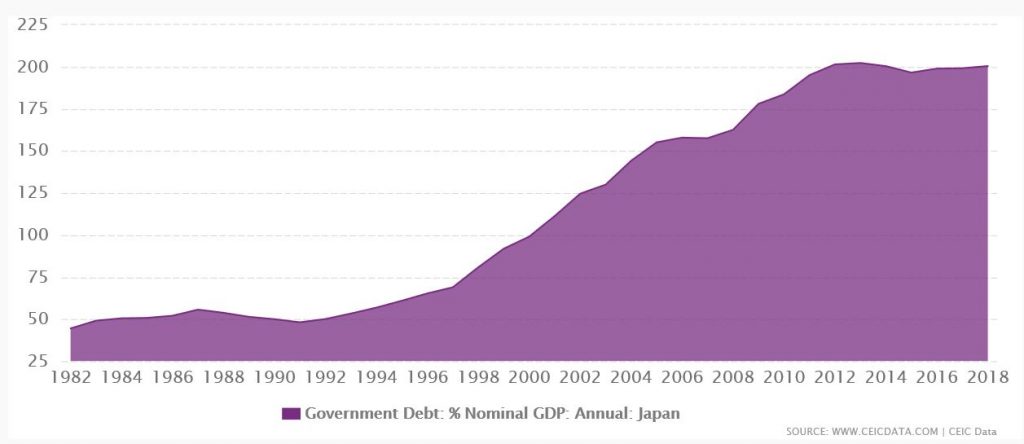

During the same period, Japan’s central government debt swelled from roughly 75% of GDP in 1999 to over 200% of GDP in 2018. Japan is now, by far, the most indebted government in the world relative to the size of its economy.

Japanese Central Government Debt to GDP

Most of Japan’s deficits are now monetized by Japan’s central bank, the Bank of Japan (BOJ). That means that the BOJ has been ‘printing’ money and buying Japanese government debt for 20 years in order to keep interest rates at artificially low levels. As a result, the BOJ’s balance sheet is now larger than Japan’s entire GDP. In other words, the monetary base in Japan is now larger than the output of the Japanese economy.

One would expect that these factors would be producing intense inflation in Japan. In reality, Japan has experienced vanishingly little inflation. Since cutting rates to zero in 1999, Japan has witnessed just 1.5% CPI inflation. That is 1.5% over the course of 20 years, not 1.5% per year. As a point of reference, CPI inflation in the US is currently running at about 1.7% per year.

Based on those details alone, it would seem as though Japan has discovered a way to print money, run large deficits, suppress interest rates, and suffer no negative consequences. Of course, there is a catch. In fact, there are several.

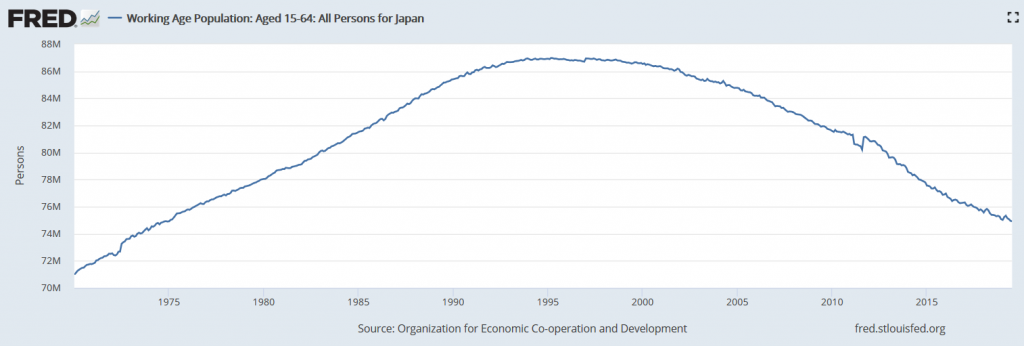

Catch 1: Declining Population

Japan’s working age population (15-64 years old) peaked in 1997 and has declined nearly 14% since then. Japan’s overall population has been declining since 2008. Furthermore, the average age of Japan’s population has risen from 41 years old in 1999 to 49 years old today, making it the most elderly country in the world. These demographic changes have been highly deflationary. Fewer young people means fewer workers, fewer consumers, fewer borrowers, and fewer home buyers.

Japanese Working Age Population

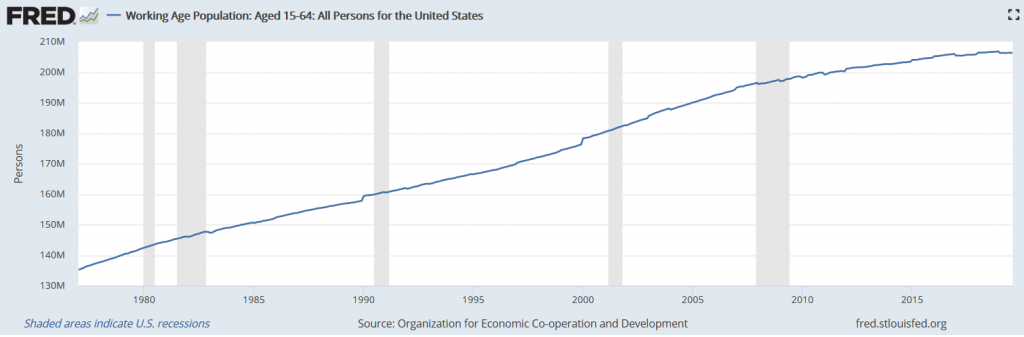

By comparison, the US working age population has grown by 17% since 1997 and, while the rate of growth is slowing, the working age population is expected to continue growing until at least 2050. The overall US population is expected to continue to grow until at least year 2100.

US Working Age Population

Catch 2: Declining Bank Lending

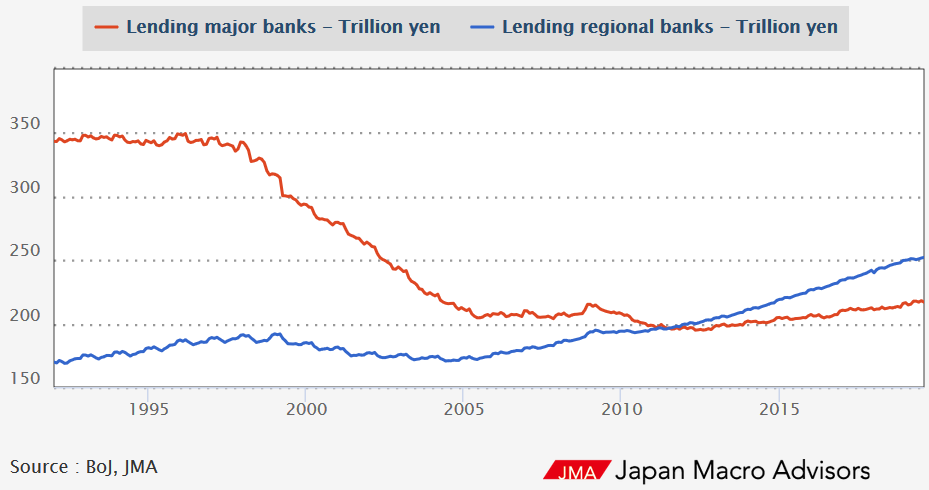

Since Japan’s working age population peaked in 1997, total bank lending has declined 12.7%. Bank lending is responsible for most of the money supply growth in an economy and is a primary driver of inflation. Japan’s deep contraction in bank lending is highly deflationary.

Japan Commercial Bank Lending

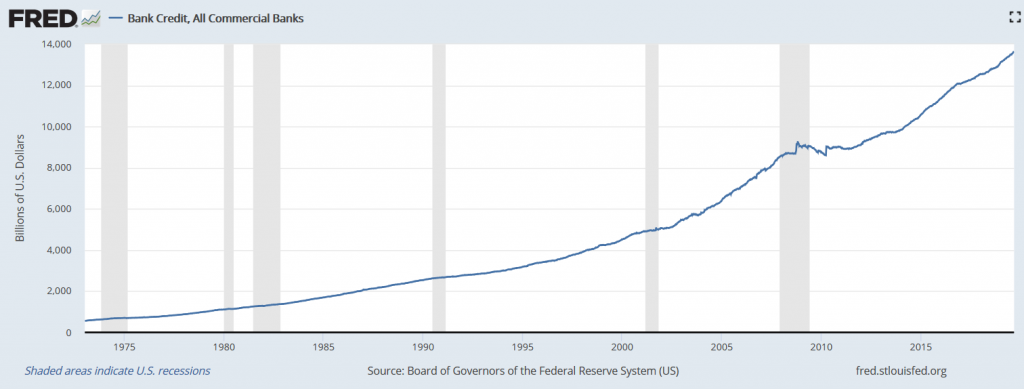

By comparison, US bank lending has grown 250% since 1997 and is currently growing by over 6% year-over-year, above average for the current expansion.

US Commercial Bank Lending

Catch 3: Very Little Economic Growth

When Japan’s population peaked in 1997, its nominal GDP was $4.41 trillion. Today, Japan’s nominal GDP is $4.97 trillion. In other words, Japan’s economy has grown 12% over the last 20 years, averaging significantly less than 1% growth per year. Slow growth implies slow investment, consumption, and production, all of which is dis-inflationary.

During the same time period, the US economy grew from roughly $8.57 trillion to $20.58 trillion. The US economy has grown 139% since 1997 and is likely to grow by over 2% this year, above average for the current expansion.

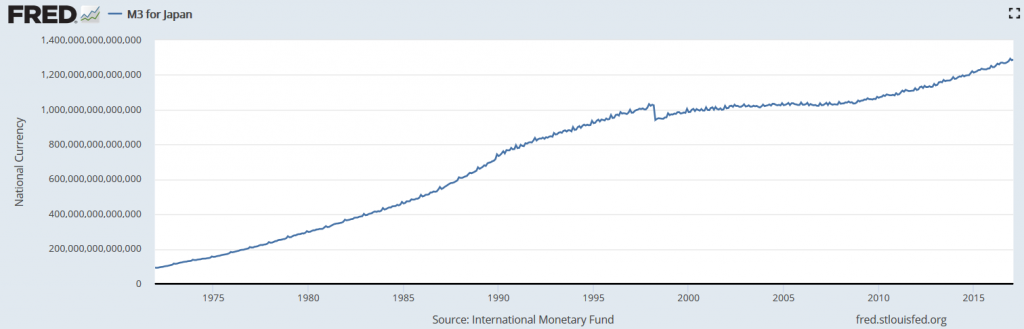

Catch 4: Modest Growth in the Money Supply

Despite Japan’s extreme monetary and fiscal policy, its overall money supply has only increased by about 28% since 1999 (as measured by M3). The growth in Japan’s money supply has been so modest because the dramatic growth in the BOJ’s balance sheet has served to offset the strong deflationary forces of a shrinking and aging population, shrinking bank lending, and stagnant economic growth.

Japanese M3 Money Supply

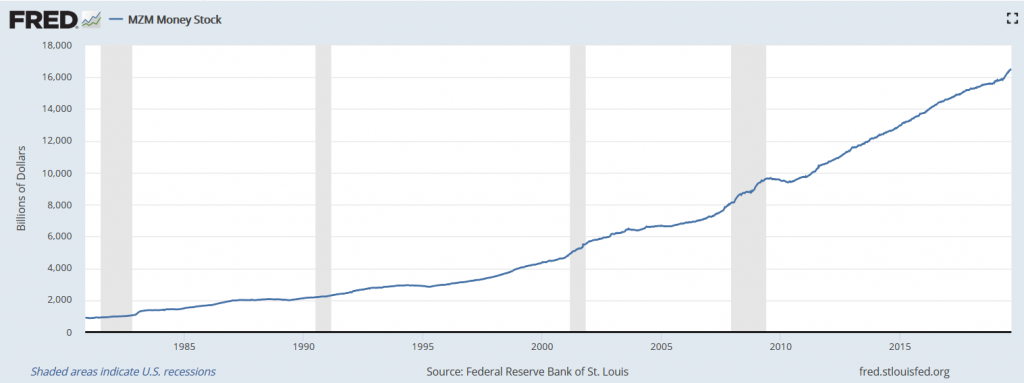

In the US, money supply has grown by a stunning 415% during the same time period and is currently growing by over 6% year-over-year, above average for the current expansion.

US MZM Money Supply

The US Is Not Japan

As the previous statistics highlight, Japan’s 20 years of fiscal and monetary stimulus have compensated for an array of deeply deflationary factors. Those factors do not exist in the United States. The proposition that extremely accomodative monetary and fiscal policy wouldn’t lead to inflation in the US because it didn’t do so in Japan ignores all of the relevant details.

Nonetheless, Japan’s experience over the last 20 years does offer several important insights into extremely accomodative policy. 20 years of zero-to-negative interest rates and large deficit spending has left economic growth and inflation right where it was in 1999. Japan is not any closer to fixing its economic problems than it was 20 years ago. Perhaps, Japan would have had a deeper decline in growth if not for these policies. Perhaps, they would have had a sharper recovery as well. We’ll never know. What we do know is that Japan is now stuck with over 200% debt-to-GDP and gross distortions in its financial markets. If Japan’s economy ever does normalize and even modestly high inflation were to return, the policy normalization that would be required to fight that inflation would be deeply painful for Japan.

US GDP, banking lending, and money supply are currently growing at rates above the average for this expansion. Employment levels are at 50 year highs, real wages are rising, financial asset prices are near fresh all time highs, and inflation is a rounding error away from the Fed’s 2% target. The increasingly popular idea that now is the time to be deploying monetary and fiscal stimulus more appropriate for combating a full blown deflationary depression is ludicrous.

Will the US have a recession in the coming years? Absolutely. There is always a recession looming in the coming years. Should the US adopt self-destructive policies that undermine the structural viability of the free market economy in a pyrrhic attempt to delay that recession? Absolutely not.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Interesting to note how the money supply is sharply lower than the growth in government debt. That helps explain the deflation. I expect the yen to someday collapse like a cheap umbrella.

The rest of the story many people forget is Japan has remained relevant because they have tied into China’s rapid growth since 2000.

Yeah, very true. Japan has been very lucky in that regard. They also run a current account surplus and a trade surplus and invested really heavily in automation

Excellent article, absolutely spot-on

Thanks!