Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 4th of February 2017 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

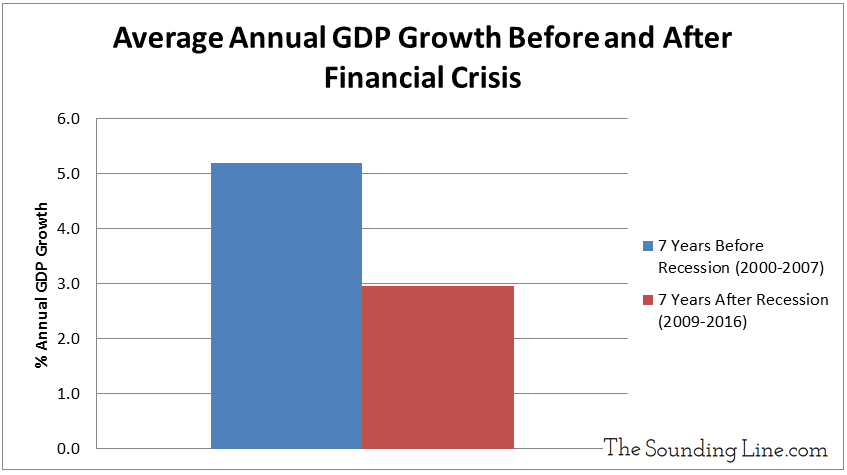

The following graph illustrates the slowdown in US economic growth since the 2008 financial crisis and recession.

The US GDP growth rate has slowed from an average annual rate above 5% to an average rate below 3% in the years following the financial crisis. Despite record highs in financial asset prices, many fundamental economic indicators have shown little to no recovery since the recession. Labor participation, capacity utilization, industrial production and many other indicators are still lower than before the crisis (see a list here).

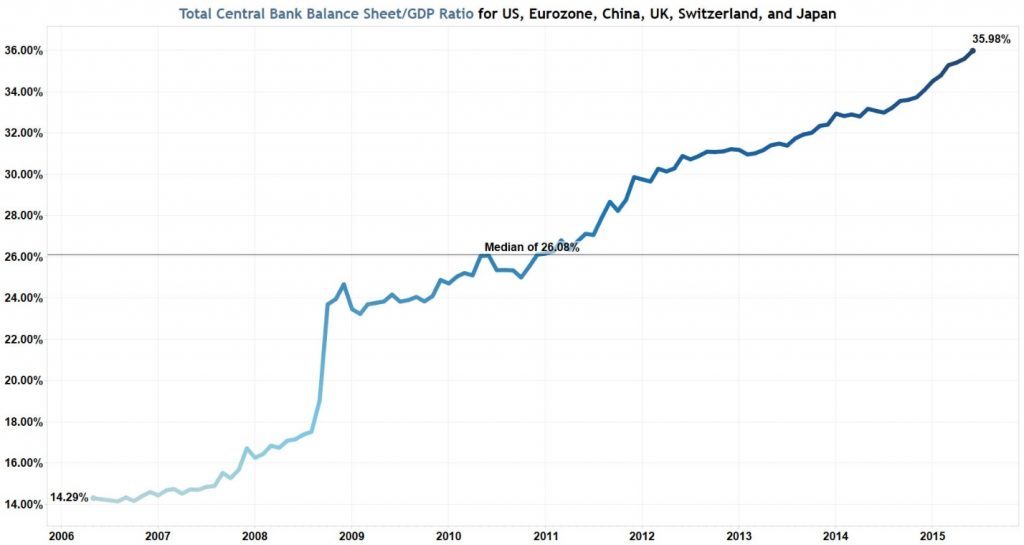

This disappointing economic recovery has taken place despite the largest monetary stimulus program in the history of the Federal Reserve: one that was co-ordinated with similar programs at nearly all major central banks around the world. These programs have aimed to lower interest rates and re-liquefy banks via quantitative easing programs (QE).

Central banks have purchased a cumulative $16.8 trillion dollars in financial assets equaling over 35% of global GDP.

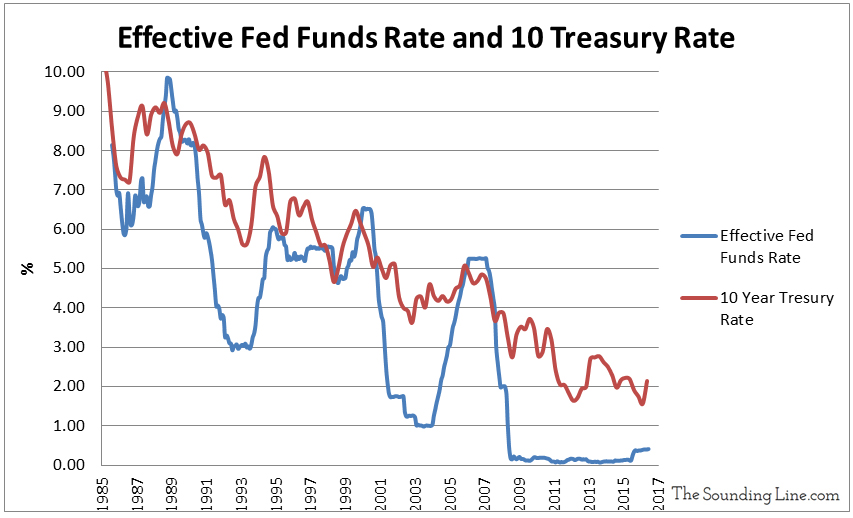

The Fed has dramatically lowered its Fed Funds Rate since 2008 and with it other interest rates have fallen.

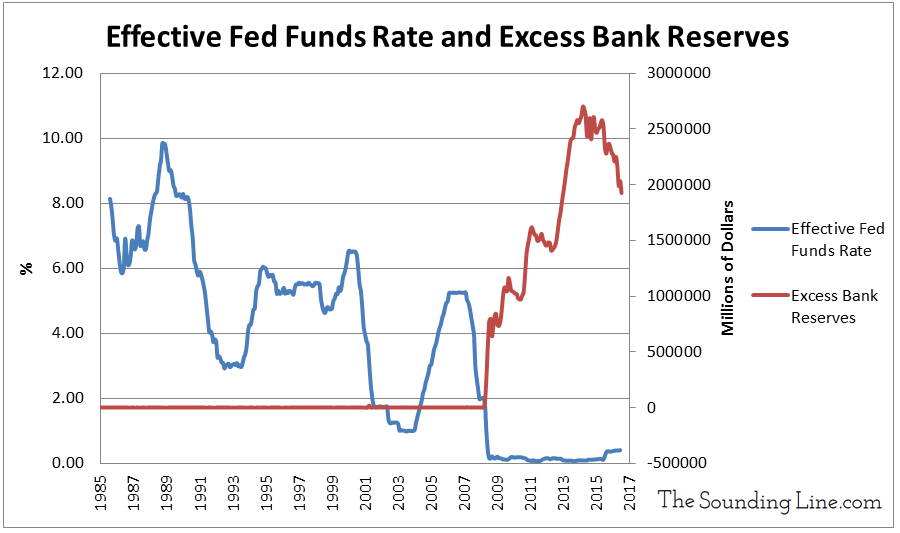

The Fed has similarly succeeded in injecting banks with massive amounts of liquidity, producing record reserves.

As a result of the Fed’s policies, interest rates are low, banks are recapitalized, and stock markets have rallied.

So why haven’t low interest rates produced underlying economic growth in line with historical averages?

Interest rates follow the same underlying supply and demand dynamics as other prices. Speaking in general terms:

When interest rates are falling it is a sign that demand for credit has fallen in relation to its supply. Falling rates mean that lenders are competing to lend to a shrinking pool of eligible borrowers. As the pool of eligible borrowers shrinks, lending slows, and so does credit creation. As credit creation slows so does the money supply and in turn inflation. Eventually interest rates become so low the lenders’ overhead costs exceed market interest rates. Below this point it is no longer profitable for lenders to lend. That reduces credit growth further and the negative cycle continues. All the while lenders’ (read banks) profits and revenues are reduced, threatening their stability and compounding problems further.

This is where the Fed steps in. To break the cycle of declining lending and declining inflation the Fed lowers its Fed Funds Rate. The Fed Funds Rate is one of the costs of lending for Banks. By lowering this cost, the Fed enables banks to resume profitably lending at lower rates than they otherwise would be able to do. Hopefully more borrowers will be credit worthy and more business plans viable at these artificially lower rates and credit growth will restart, ending the negative cycle.

That’s the theory. Here is why it hasn’t worked:

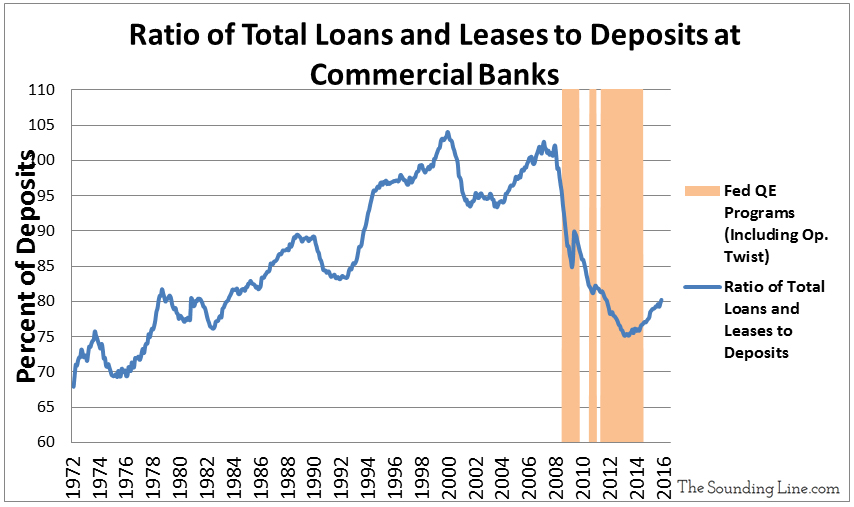

It is important to separate the root cause driving the cycle of weakening demand for credit from the symptoms. Declining interest rates and inflation are the symptoms not the cause of the current economic slowdown. The Fed has attempted to treat the symptoms not the disease. Accordingly they have had little success. Credit worthy borrowers did not become seldom because interest rates rose too high, borrowers became seldom because the financial crisis exposed, and compounded, growing structural problems accumulating in the US economy. These problems have only worsened since the crisis. Fewer people are creditworthy and fewer opportunities for economically viable loans exist as result of these problems, even at lower rates, and so credit growth has remained slow despite low interest rates. The chart below shows that the ratio of loans and leases to bank deposits plummeted following the recession and remains very low today. Banks can’t lend if eligible borrowers don’t exist.

That brings us to the underlying problem: Practically speaking, the US has the highest corporate taxes IN THE ENTIRE WORLD (here). Large multinational companies don’t pay these rates, but small and medium sized companies do. These same small and medium sized companies have also been extremely disadvantaged by the increased cost of compliance associated with geometrically increasing quantities of regulations (here). Once again it is large companies who can afford the cost of compliance and thus gain a competitive advantage in increasingly regulated industries. As a result of over taxation and over regulation, the startup rate of new companies is the lowest on record and has fallen below the rate at which companies are closing. Disadvantaging small and medium sized companies undermines the US economy. They are the largest employers in country (here) and it is new companies, less than 5 years old, which account for all of the net job creation since 1992 (here).

The US economy needs dramatic structural reform: lower taxes and less regulation. The Fed cannot be blamed for wanting to help, but its attempts to manipulate asset markets and risk premiums have not only failed to produce real economic growth, they have created the exact kind of market imbalances that led to the last financial crisis. They have also distracted from the real problems.

For the first time since the last crisis, the US has political leadership that has articulated a strategy to cut taxes and regulation. Small wonder that strategy was so vehemently opposed by those whom have benefited from the overtaking of the US economy by large corporate and financial interests.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.