Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 1st of July 2019 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe.

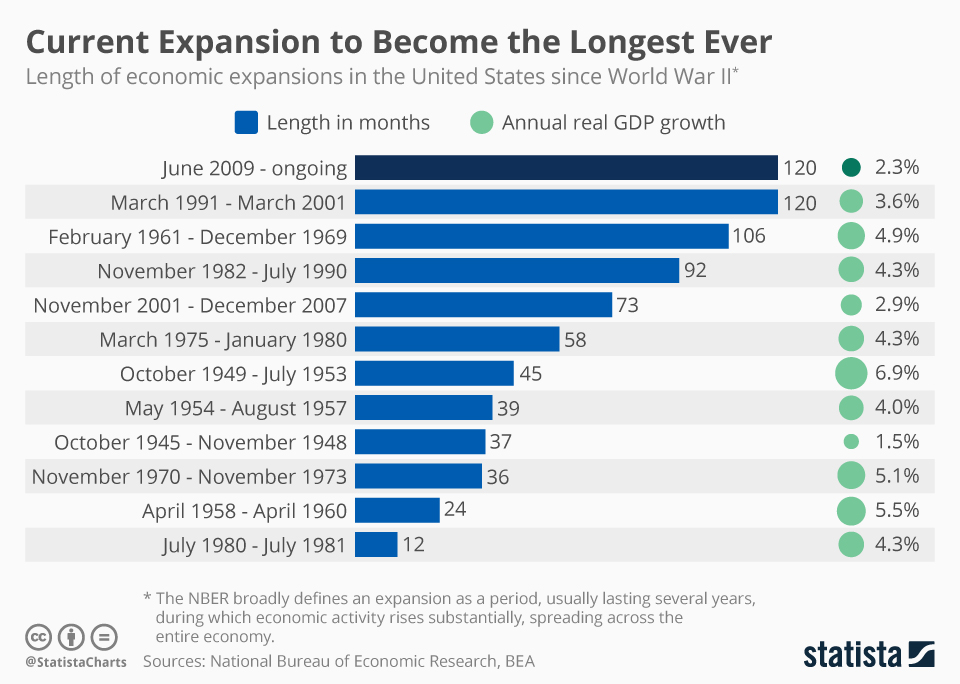

As of the 1st of July 2019, the ongoing US economic expansion has lasted over 120 months. It has now outlasted the 1990s expansion to become the longest expansion in recorded American history. Since 1854, the average economic expansion lasted just over three years. Since World War II, the average expansion lasted slightly less than five years. The current expansion has lasted ten years and counting.

You will find more infographics at Statista

The US has also been in the midst of the longest bull market in American history since last August. We came extremely close to ending that bull market in the fourth quarter of 2018 (defined as a 20% decline in the S&P 500), but technically avoided it.

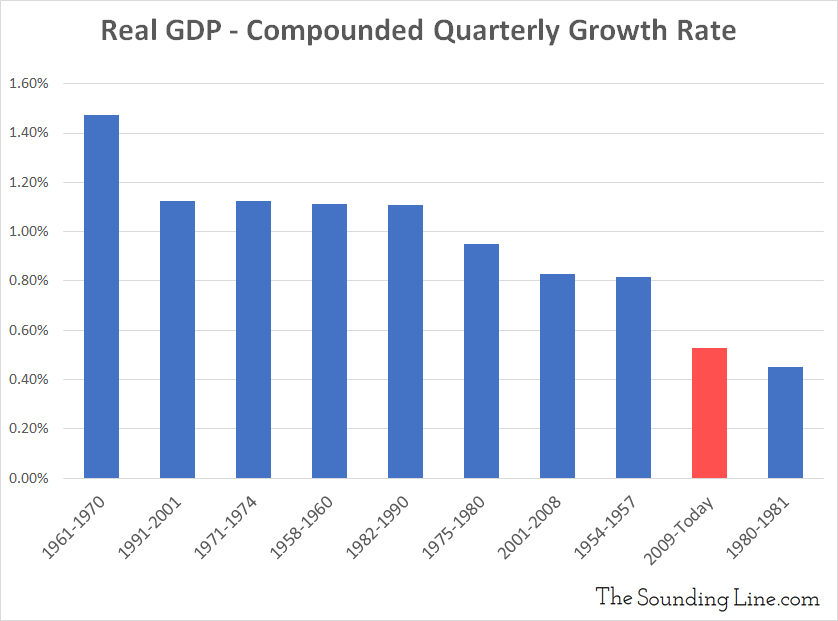

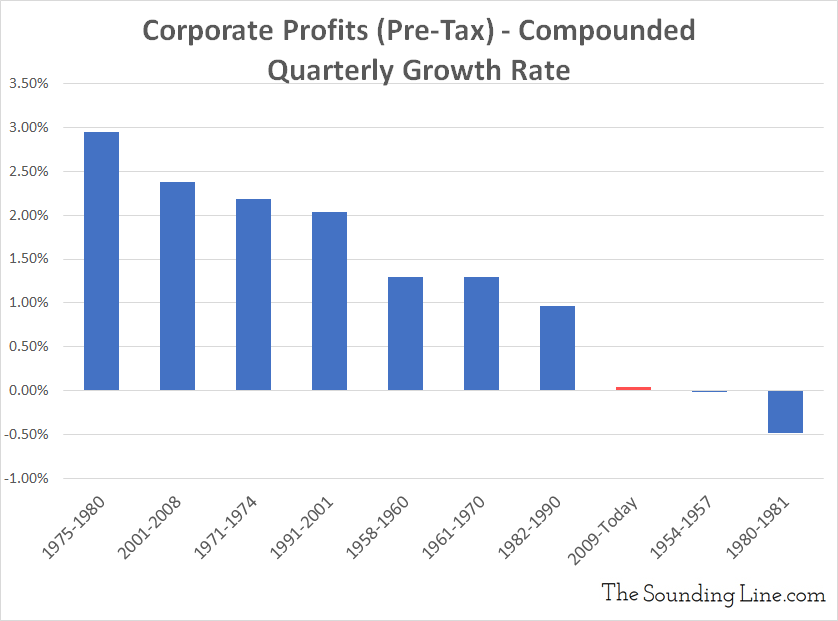

While the current expansion has been the longest, it has been far from the strongest. When looking from cycle peak to cycle peak, the current expansion has seen slow GDP growth, slow corporate profit growth (pre-tax), and slow equity appreciation.

Last summer, when the US crossed the milestone for longest bull market in US history, I noted that:

” Not for everyone and not equitably, but if there is such a thing as economic ‘good times,’ these are they… We all know that good times don’t last forever. The question is: how long can they last for? In the search for a useful analogue, parallels are being drawn between virtually every period in American history… The truth is that useful parallels can be drawn with virtually every economic cycle because they all share similar attributes: excess liquidity leading to asset bubbles followed by constricting liquidity which reaches some always-hard-to-forecast critical level, popping the bubble. The US is now somewhere in that constricting phase. While various analysts point to different economic cycles in American history, they all point to the same period in those cycles: the part within a year or two of the bubble popping. While they may all be wrong (it happens), history is on their side. Tightening cycles virtually always end in recession, usually within a handful of years. So while times are looking good, and there will inevitably be a certain momentum to that fact, there is no better time to contemplate what has always come next: not good times.”

When the passage above was written, the Federal Reserve was raising interest rates and reducing its balance sheet. Today, the Fed is now considering a cut to interest rates and a restart of QE. Many central banks have already cut rates or eased lending rules.

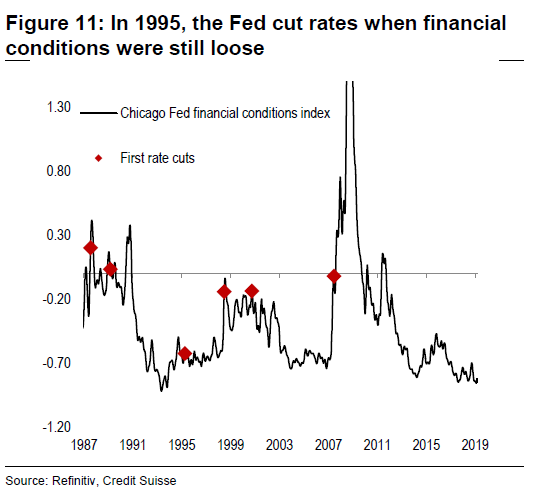

It is typical for central banks to begin to reverse tightening policy in the very late stages of an expansion. Sometimes is gives the expansion an extra leg, such as in the late 1990s, and sometimes it doesn’t.

I fear, however, that the dovish pivot currently underway is not consistent with historical analogues and may represent a secular shift in monetary policy. The Fed has never cut interest rates with liquidity conditions this accomodative. In fact, liquidity conditions have rarely ever been this accomodative.

Central banks seem to have adopted a strategy of using all of the tools within their power, including the arsenal of unconventional tools created since the Financial Crisis, the avoid recessions at any cost.

Recessions are a healthy, necessary part of the economic cycle. They keep investors, businesses, and households disciplined. They remove overcapacity and make room for innovation and evolution. The US has endured 42 recessions and five depressions since the 1780s. The US economy recovered from every single one, returning to growth within an average of roughly one and a half years. That includes the 39 recessions and depressions that proceeded the establishment of the Federal Reserve in 1913, and the 20 that occurred when the US had no central bank at all. The eras of the most robust growth in American history have been punctuated by frequent recessions, not long stretches without them.

The increasing stretch of time since the last recession is evidence of a growing cult of ideology among central bankers who believe it is possible and desirable to eliminate recessions. It is neither. While they may succeed to forestall the next recession yet further, it comes at the cost off continued mis-allocation of capital and rising debt levels.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.