Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 20th of February 2016 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Nearly eight years after the financial crisis and despite one of the longest, largest stock markets bull runs in history, artificially low interest rates are still dominating the global economy.

For many countries, interest rates are still being manipulated lower. Since 2014, 19 Eurozone countries, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland, and Denmark have issued sovereign debt at negative interest rates. According to Bloomberg, $7 trillion of bonds have been offered with negative yields, accounting for 29% of Bloomberg’s developed sovereign bonds index as of the 6th of February 2016.

Central banks around the world have purposefully manipulated interest rates lower since the 2008 financial crisis in an attempt to create and sustain an economic recovery. Behind this effort is a singular belief called the ‘wealth effect.’ This idea has directly led to the most radical central bank policy in modern times, the lowest interest rates in human history, and arguably the printing of more currency than in all previous human history combined.

The ‘wealth effect’ has supplanted the very foundation of free markets and capitalism. Articulated by Adam Smith in 1759, the most foundational truth of capitalism is that the ‘invisible hand’ of free markets will do a better job balancing supply and demand and pricing risk than bureaucrats.

Interest rates directly or indirectly effect the supply demand balance and price of everything in an economy from stocks, bonds, commodities, to real-estate and labor. The ‘wealth effect’ has replaced the idea that prices are best set by free markets with the idea that prices should be set directly, or indirectly, by bureaucrats at central banks.

What is the ‘wealth effect?’

The ‘wealth effect’ is the idea that if central banks artificially lower interest rates, people who have their money saved at banks or in low risk bonds will react to the new lower interest rates by moving that money into potentially higher risk/reward assets. Examples would include stocks, real-estate, or higher risk bonds. The cumulative effect of many people doing this will drive up the prices of these assets. If the value of these assets goes up, people will make money that they will spend in the ‘real’ economy. Voila, self-sustaining economic growth has been realized.

In this post we will discuss conceptual issues with the ‘wealth effect’ by attempting to answer the following question:

Is there a net longer term economic benefit afforded when the Federal Reserve artificially lowers interest rates?

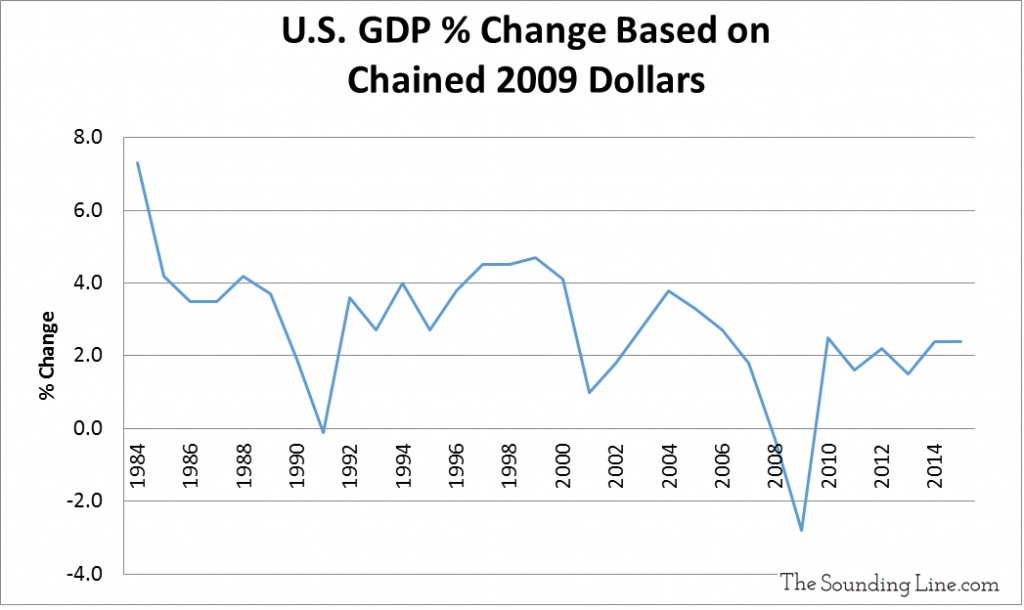

Since the Fed began lowering interest rates and executing quantitative easing (QE) starting in 2008, they have succeeded in driving the stock market and bond valuations to record highs. According to the ‘wealth effect’ this should have translated to great improvements in the ‘real’ economy. The truth is quite different. Despite record highs in stocks and high risk bonds, proportionality fewer people are working, wages haven’t grown meaningfully, a record wealth gap has emerged, commodity prices are declining, U.S. imports and exports are declining, and GDP growth has stagnated. It hard to argue based on those facts that higher stock prices lead to an improvement in the ‘real’ economy. This simply has not happened.

- The wealth gap between the wealthiest and everyone else hasn’t been higher since record keeping began (link here).

- The majority of the improvement in the unemployment rate since 2008 is due to people leaving the labor force, not getting jobs (link here). The percentage of working age people with jobs is far lower than before the 2008 recession.

- The percentage of people in the labor force under 55, under 25, and under 19 is lower than before the recession.

- The percentage of people not in the labor force who still want a job has increased since the recession. These are individuals who are not being counted as unemployed but who want a job.

- Real hourly private sector wages are still lower than in 1971 (link here).

- Commodities, which should be in high demand in a growing economy, have seen demand suffer resulting in prices that have been declining since 2011 (link here).

- Both U.S. imports and exports declined in 2015.

- The GDP growth rate is below per-recession levels.

The wealth effect hasn’t worked because the ‘wealth effect’ doesn’t make logical sense. Consider the following:

In order to concentrate money in an asset class, stocks for example, that money most come from somewhere else, or be printed. The gains and profits made by money accumulating in stocks will be offset by losses resulting from money leaving other asset classes or sectors of the economy. Similarly, if the Fed prints money to inflate one, or several asset classes, the increase in the quantity of money is offset by a commensurate decrease in the value of money, i.e. inflation.

The extra wealth created by people crowding into stocks as a result of low interest rates, will be no greater than the profits lost on interest income on savings at the bank or in bonds bonds, or value lost to the effects of inflation, or investment in real factories and equipment forgone to pursue corporate stock buybacks.

To put some numbers to these assertions, consider this.

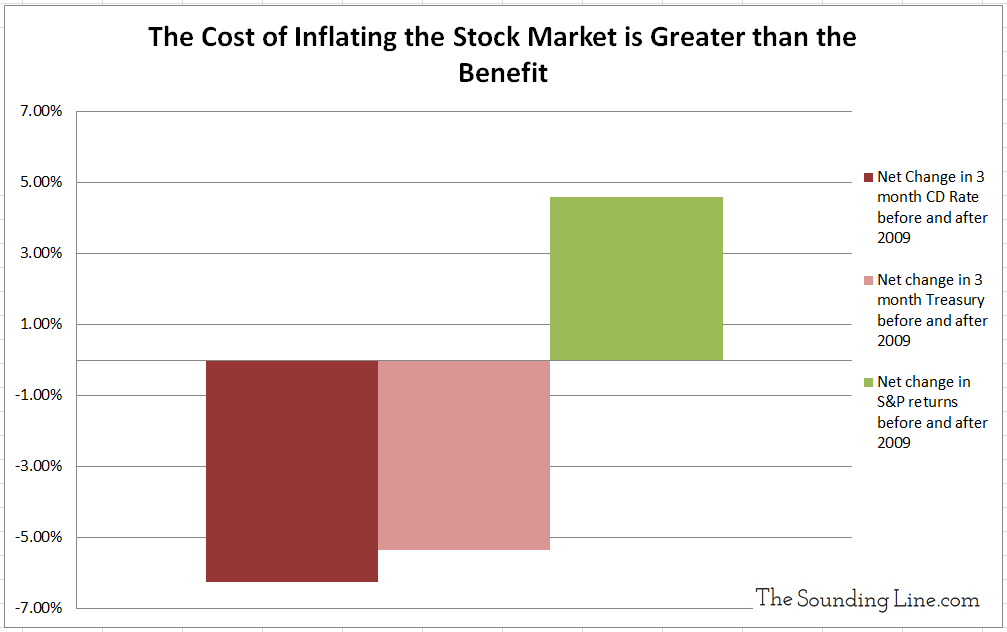

- 92% of Americans have a bank account (link here). Before 2009 and going back to 1971, these people earned an average of about 6.6% interest on 3-month CDs at the bank (link here). Since 2009 and the Fed’s ‘Zero interest Rate Policy’ (ZIRP), these very same people have earned less than an average 0.35% on the same instruments. That means that the 92% of Americans with bank accounts have lost roughly 6.25% interest a year on their savings because the Fed manipulated interest rates lower.

- The average yearly return on 3-month treasury bills, a low risk bond, averaged 5.43% from 1960 through 2008. It has averaged 0.10% since 2009 (link here). The trillions of dollars invested in treasuries since 2009 have lost, very approximately, 5% return per year due to the Fed’s policies.

- At the same time, only 55% of Americans own stocks and that percentage has actually decreased since 2008 from 62% (link here). The simple fact is that almost half of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck and/or don’t have enough savings to invest in stocks.

- The average yearly return on the S&P 500 from 1960 through 2008 was 10.5% and the average yearly return from 2009 to 2015 has been 15.11%.

- Putting this all together, 92% of Americans forewent 5% interest income on their savings and bonds as a result of the Fed’s low interest rate policy, so that 55% of Americans with stock holding could increase their returns by 4.6%.

People that live pay check to pay check, who cannot afford to invest in stocks, by definition are spending more of their income than people who are saving and investing in stocks and bonds. Providing 4.6% increased annual earning potential to fewer, wealthier, higher risk stock investors by taking away 6.25% earning potential away from far more people who spend a far greater percentage of their income decreases total spending and consumption. There is simply no ‘wealth effect.’

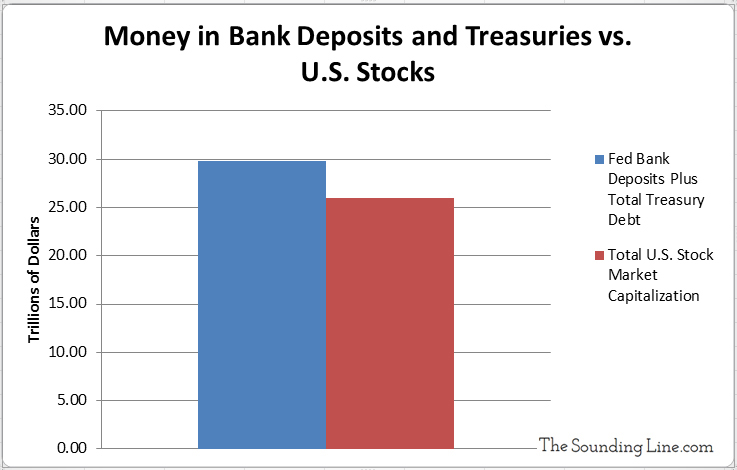

The amount of money deposited at banks and saved in bonds is still larger than the money invested in the stock market. That means that a larger amount of money is losing earnings in order to create higher returns for a smaller riskier amount of money.

Furthermore, the assertion that money held in stocks or high risk bonds is more productive than money held at the bank does not hold water. Banks use deposits to finance entrepreneurs, startups, and small and medium sized businesses. These are by far the largest employers in the country and the engines of innovation and growth. Companies that are listed on U.S. stock markets are generally larger, established businesses which have increasingly used their resources on stock buy-backs instead of capital investment.

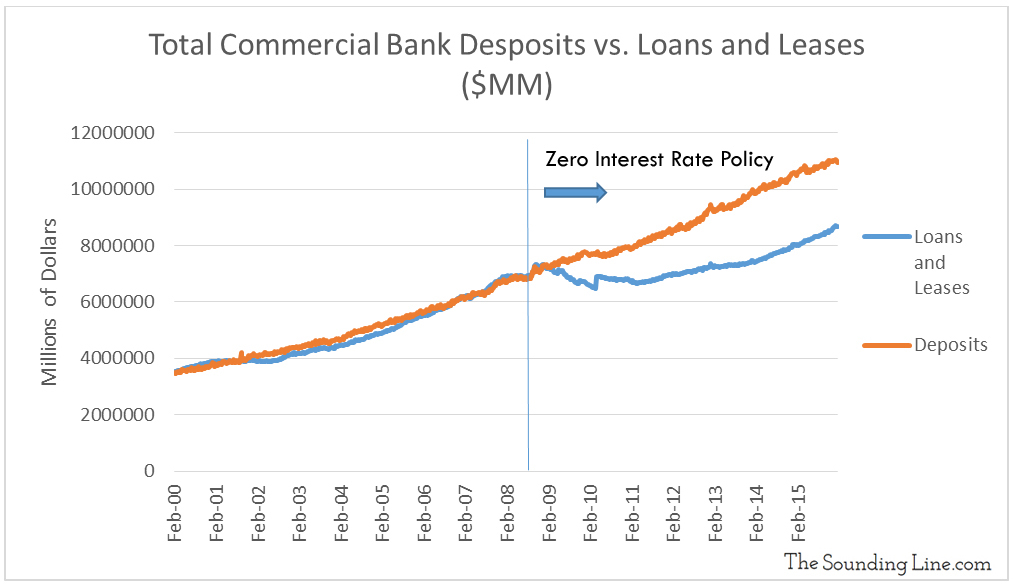

At this point the astute reader may contend that lowering interest rates allows that banks to loan more money and thus there is an economic benefit to low interest rates that we have failed to capture thus far. This is not necessarily true.

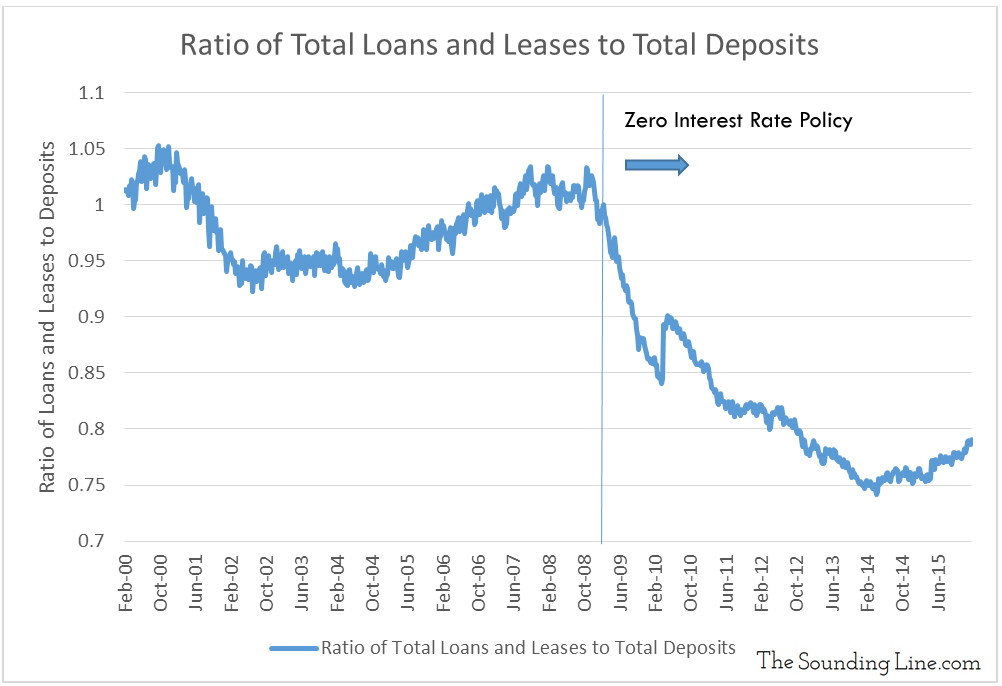

The amount that banks can loan out is a function of the amount of deposits they have, demand for loans, the cost of lending, and their ability to find people who are sufficiently credit worthy. As the two charts below show, historically banks were highly efficient in loaning out the maximum possible amount permissible based on their reserves. However, since 2008 and low interest rates, the banks have continued to build reserves at the same historical pace thanks to the Fed, yet they are loaning proportionally less money. At the end of the day the bank’s need to find credit worthy borrowers with sound plans to to generate the returns needed to repay loans. In our weak economy, it is not the cost of lending that constrains credit growth, it is the ability to find worthy recipients and project to lend too.

At its heart, the so called ‘wealth effect’ is nothing more than taking $5 from your left pocket, putting it in your right pocket, and proclaiming that you are $5 richer.

The ‘wealth effect’ has succeeded in making the wealthy wealthier by depriving the majority of people of vitally needed earning potential that they would have actually spent in the real economy. The ‘wealth effect’ has artificially driven wealth into higher risk assets and has, by design, inflated those asset values.

What does the Fed think will happen to the wealth in higher risk assets if the higher risk finally materializes? How does the Fed expect to ever normalize its policy if high stock valuations are primarily a result of the Fed’s abnormal policy? What happens when all of the money that is willing to move into high risk assets has done so; how will those assets continue to rise?

The answer to these questions is simple. Interest rate policy has not normalized because it cannot normalize without incurring loses in risk assets. Stock prices rose because of lower interest rates and, without structural reforms, they would fall because of high interest rates. This is the definition of a bubble. It is hard to fault the Fed for wanting to stimulate a fundamentally weak economy but the ‘wealth effect’ doesn’t work and doesn’t hold up to serious scrutiny. Little is more concerning than the fact that it forms the foundation of central bank theory around the world.

How can lending and credit growth be restored? Long overdue and badly needed structural reforms to regulatory, tax, fiscal, and trade policies. What ails the US economy is not a lack of central bank interventions but a increasingly byzantine regulatory framework.

P.S. We have added email distribution for The Sounding Line. If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.