Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 17th of 2018 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe.

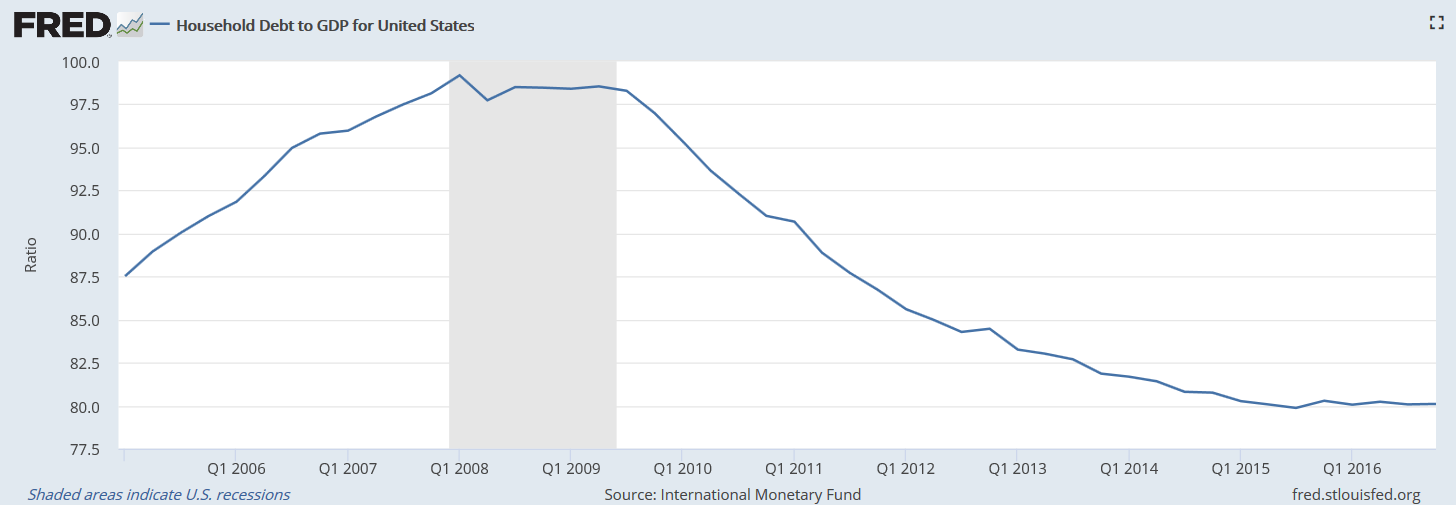

During the US Housing Bubble, artificially low interest rates and loose lending standards led household debt to surge from roughly 70% of GDP in 2001 to 99% by the first quarter of 2008. The rapid debt growth set the stage for the worst global economic crisis since the Great Depression.

Willingly or not, US households have deleveraged relative to the economy and their disposable income since the 2008 financial crisis. Household debt has fallen back to roughly 78% of GDP (though absolute US household debt continues to climb).

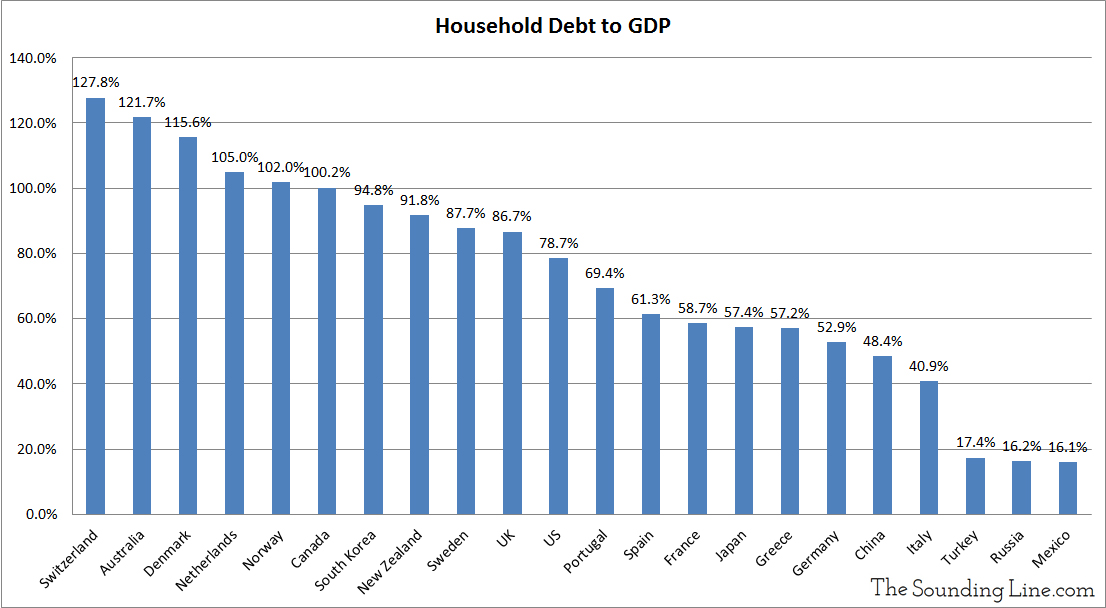

However, not everyone is deleveraging. The following chart shows household debt to GDP levels for the world’s leading economies in 2018:

Switzerland, Australia, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, and Canada all have household debt levels higher than the US during the peak of the Housing Bubble and the debts have been growing at a rapid pace. Since 2009, household debt to GDP has surged roughly 25% in Norway and 23% in Switzerland compared with 27% for the US from 2001 to 2008.

The European Central Bank, the Swiss National Bank, and the Bank of Canada have kept interest rates at or near negative levels for nearly a decade. Low interest rates have shielded households in these countries from the real costs of borrowing and allowed them to get used to spending more than would be sustainable with normalized interest rates. Three things will inevitably happen when interest rates and the cost of debt normalizes: household spending will fall as borrowing is reined in to adjust to higher interest expenses, businesses that rely on inflated household spending will see their revenues drop, and banks will be hit by slowing credit growth and increased defaults from business and households. All of this will lead to layoffs and further economic slowdown.

This is what happened during the US housing crisis when the artificially low interest rates and easy lending standards of the early 2000s ran into modestly rising interest rates and tightening standards in the mid and late 2000s.

The lesson of the Housing Bubble and Great Recession was that keeping borrowing conditions artificially easy in order to boost growth in the early 2000s created an unsustainable debt bubble that led to a very painful recession. So far, the ‘fix’ to that recession has been to keep interest rates even lower for even longer and allow debt levels to rise even higher. While US households and lenders have avoided repeating the exact same mistake, other countries and sectors of the economy have not heeded the lesson. Whether it is household debt in Switzerland, government debt in the US, or corporate debt in China, debt bubbles abound. While the US Federal Reserve has prudently been tightening monetary policy for several years, many central banks are keeping interest rates at or near record lows and still performing QE, apparently hoping that sustainable economic growth is just around the corner. Yet sustainable economic growth arises from structural reforms to the economy not distorting monetary policy. In fact, ultra-accommodative monetary policy has masked and delayed the need for pro-growth structural economic reforms around the world.

While it won’t unfold exactly like the housing crisis and it may not be for a while, whenever the next economic crisis arrives, the lesson will be the same. Boosting economic growth by keeping interest rates too low creates bubbles that inevitably pop in destructive ways.

If you would like to be updated via email when we post a new article, please click here. It’s free and we won’t send any promotional materials.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.