Submitted by Taps Coogan on the 29th of April 2017 to The Sounding Line.

Enjoy The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.

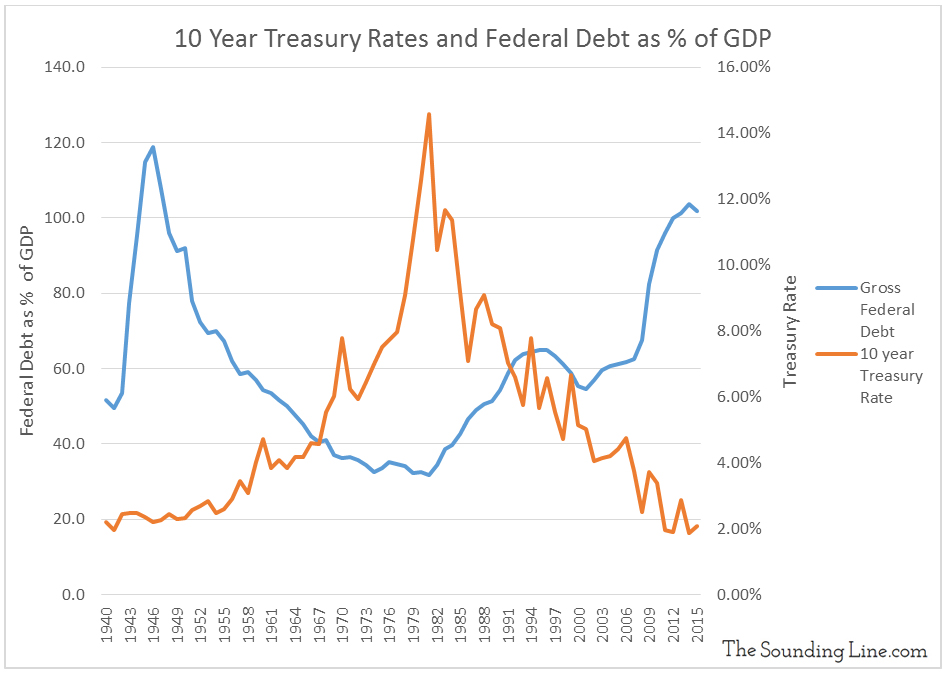

Whether the 35+ year era of declining benchmark interest rates is finally ending is perhaps the most important question facing long term investors today.

Many of the most prominent investors, analysts, and economist have weighed in on this question and it appears as though two schools of thought are emerging.

The first school says that the low in benchmark rates has already been achieved, and rates will move higher in the next year or two. The factors that will drive the rise in rates may be: the renewed inflation seen since Trump’s election, the drive by the Fed to raise rates and reduce its balance sheet, and/or debt crises around the world (particularly in the EU). Because enormous debts have built up in the current era of extremely low interest rates, and because of central banks’ desire to end the monetization of sovereign debt at artificially low rates, a rising rate environment will be highly destabilizing.

A strong argument of this school of thought comes via Martin Armstrong.

The second camp says that rates are going to stay low for a very long time and may go even lower. Developed economies are likely to stay in the same liquidity trap that has plagued them for years and continue to experience stagflation and slow economic growth. Historically speaking, lows in interest rates are often maintained for decades and we have ‘only’ been below long term median benchmark rates for 8 years.

A strong argument for the second school of thought comes via Lance Roberts at Real Investment Advice.

Only time will tell which one of these camps is correct. Here at the Sounding Line, we have expressed many of the same concerns as Martin Armstrong about sovereign debt (here, here, here), the stability of the Eurozone, and the inflationary impact that a draw down of excess reserves would have. It seems probable that if the Fed, the ECB, or the BOJ, persists in reducing their balance sheet, it will cause rates to rise. One of the largest buyers of sovereign debt would be exiting the market. Rates would have to rise in order to attract enough private capital to to make up the difference. That capital would come from some other asset class (corporate bonds, stocks, real-estate, etc…) or excess reserves held by banks. The process could cause sell-offs, inflation, and very unpredictable market dynamics. The real question then becomes, why would the Fed, ECB, or BOJ persist in normalizing policy in the event of such turbulence? Why wouldn’t they pause, or even reverse course? If they did, central banks could drag the process out for many years, bringing us to the second school of thought: rates will remain low for years to come.

It seems to all come down to the question of whether central banks will have the policy flexibility and competency to prevent the market from getting ahead of them. They may be able to walk that tightrope for a while, but the longer the low rate environment persists the greater the debts will become, and the more difficult the balancing act will become. While low rate environments can persist for decades, current global debt levels likely cannot.

Would you like to be notified when we publish a new article on The Sounding Line? Click here to subscribe for free.